By Contributing Writer Flaminia Incecchi

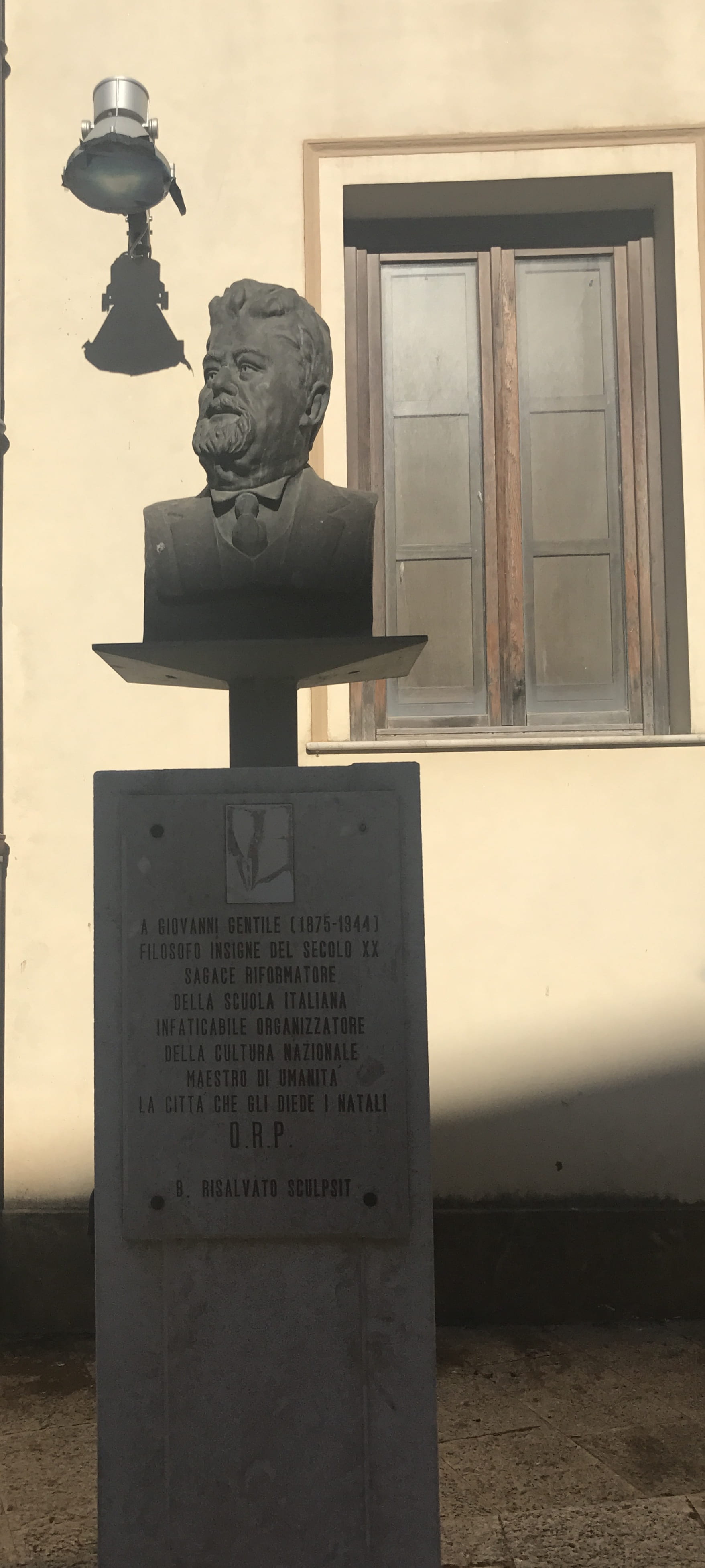

The only existing memorial to the once-famous philosopher Giovanni Gentile is in his native city Castelvetrano, a modest country town in the Sicilian province of Trapani. The memorial was made by a local artist in 2007, and it is entitled ‘Le Pagine del Filosofo’, literally, “The Philosopher’s Pages”. It is located in the small city center, in a tranquil square adorned with emerald green ficus trees, in the vicinity of a school and a museum. The square is traditionally Sicilian: tuff stone buildings of different heights, vibrant green trees trimmed to perfection. The sculpture is impressive, stark, but oddly enough, hidden at the piazza’s edge. It is a stately bronze page engraved with passages from Gentile’s philosophical texts. But a slash runs through the page, thus leaving the reader unable to continue Gentile’s thought. The memorial portrays an interrupted thought, a voice silenced mid-sentence.

Giovanni Gentile remains to this day one of Italy’s most illustrious, prolific, lucid and problematic thinkers. Born in 1875, Gentile received a prestigious scholarship to study in Italy’s most renowned institution, the Normale, in Pisa. His intellectual career lasted almost 50 years, during which he authored several volumes on the history of Italian philosophy and cultural and political history, translated texts of Immanuel Kant, constructed a highly sophisticated philosophical system called actual idealism, and penned commentaries to several philosophical texts. Gentile’s corpus amounts to almost 60 volumes. It challenges disciplinary boundaries, ranging from philosophy to history, to political articles, to texts on philosophy of education, to commentaries on Ancient Greek philosophers; and essays of the most varied content, from the concept of love, to the meaning of decorative arts, to the aesthetics of cinema, as well as nostalgic papers re-evoking Italy’s Unification period. His philosophical system is an entirely original encounter of an Idealist philosophy stemming out of Hegelianism with Italian philosophical thought. The crux of Gentile’s philosophy is the idea that the human spirit is the creator of all reality, in other words, that there is nothing which is not created by the human subject through thought. This makes the human subject the very center of all there is, conferring it absolute freedom. Gentile’s philosophy is a system, which is to say an apparatus stemming from a metaphysical core and branching out in several directions, such as history, ethics, and aesthetics. The nature of Gentile’s philosophical elaborations is to this day highly original and has much to offer to students and scholars of the humanities. So why does Gentile lie in oblivion?

Despite the profoundly theoretical character of Gentile’s elaborations, Gentile became a strong advocate of Italy’s participation in the First World War, on the grounds that only war was capable of molding the Italians into a nation. Gentile had lamented that despite the spirit of the Risorgimento (the period of Italian unification), the Italians still thought of themselves as citizens of a particular city or province, not of a nation. In his eyes, the propulsive force of the Risorgimento could only be renewed by a conflict, for conflict alone is capable of merging individual interests in a universal will. Gentile welcomed the war, not because he wanted to eradicate a particular enemy, but because only the struggle of war could create an internal friendship between individual Italians, and thus unify a fragmented people.

Gentile’s advocacy for war came to be known to the Fasci, the group headed by Mussolini that would later become the Fascist party. In 1923, Gentile became the Minister of Education for the Fascist Regime. During his tenure, he initiated a complete overhaul of the Italian education system. Schools were completely state-centralized, and education profoundly oriented towards the humanities and the formation of the future ruling classes. Mussolini praised the new school system as “the most Fascist of Reforms”. In 1925, Gentile penned The Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals, singed by the Italian intelligentsia that pledged allegiance to the Regime and endorsed its credo. In 1929, Gentile ghostwrote the philosophy (or metaphysical backbone, as it is often called) of Fascism, the Origins and Doctrine of Fascism, published under Mussolini’s name. During the Ventennio Fascista, Gentile initiated a number of cultural enterprises geared at the systematization of Italy’s cultural capital, among these, founding the Italian Encyclopaedia, along with several cultural centers.

Gentile was killed in 1944, aged 68, by a GAP (Gruppo Azione Patriottica) cell. The circumstances of his death are still mysterious.

After the demise of the Fascist Regime, students of philosophy moved beyond the Idealist ‘hegemony’ that had characterized the Italian intellectual panorama for almost fifty years. Intellectuals were keen to explore alternative philosophical avenues and re-join the debates outside the country. As a result of this desire to move beyond the ‘domestic’ intellectual landscape, as well as the intention to embrace a new dawn after fascism, Gentile was largely forgotten. The question for today, is how to remember a philosopher, whose thought might be rigorous, impeccable even, and whose pen was decisive in the writing of Italian history in an unprecedented manner, but whose political actions, allegiances and beliefs, have turned out to be disastrous.

Until a few years ago, the few people who published on Gentile were largely ideological, and their work read more like a denouncement of Gentile’s actions, with the aim of ascertaining whether he was actually a Fascist. These works by and large, tried to establish a continuity between Gentile’s philosophy and the metaphysical backbone of Fascism, in other words, to what extent his philosophy was congruent with Fascism, or Fascism with his philosophy. There were few genuine investigations of his intellectual work. Today there are hints of a germinal interest in Gentile, suggesting that we are moving beyond the epoch of ideologically-driven investigation, and perhaps entering a landscape of unprejudiced intellectual inquiry, but Gentile remains under-read considering his importance.

Moving outside academic circles, there have been a few initiatives sponsored by the Italian government to commemorate the death of the philosopher, particularly that of 1994, which saw the emission of a stamp with Gentile’s portrait. More recently, in 2004, the Senate of the Republic organized a conference on Gentile, involving Italy’s most high-profile experts on his thought.

Gentile’s memorial in Castelvetrano is of great interest because of its unproblematic nature, which is largely determined by its location, the initiators of the remembering, and what the sculpture symbolises. Situated in his birth city, it is a commemoration of the most illustrious citizen of a modest rural town in one of Italy’s most disadvantaged provinces. There is nothing political, partisan, or controversial about it. It is a local memory of a prestigious – if not the most prestigious – local. The monument is free of the problematiques that an institutional statue would comport: it is a local initiative, entirely independent from commissions of the Italian government. Regardless of the sedimentation of the ashes of history, The Philosopher’s Pages has, I believe, a radically different spirit compared to institutional acts of remembering. It is a town, remembering one of their own, within their walls, for the intellectual stature he reached, a stature by all means infrequent. The local flavor, essence, and position of the memorial is what makes it unpolitical and free of polemic. In this sense, even the location within the location is worth noting: the memorial is not situated in the center of the piazza, but on the side, almost hidden or sheltered by the ficus trees. The lack of partisanship and the local aura of the memorial is highlighted by the silence surrounding it: national newspapers have not reported the issue; no commentators or intellectuals have discussed the monument. The absence of discourse exorcises worries related to a reactionary memory of the thinker. The Philosopher’s Pages is a peculiar fusion of memories: the philosophical and the personal.

In this vein, it is important to note that the passages engraved on the statue come only from Gentile’s philosophical works. This suggests that it is only Gentile, as philosopher, that is being remembered. It symbolizes the ruptured life of an intellectual – thus a page that has been ripped – a voice that has been muted. The flavor would, of course, have been quite different had the memorial included passages from other, more controversial works. In addition, the location – Castelvetrano – suggests a memory of a personal nature, the local dimension. Here the Gentile being remembered is also the person, not in the political sense, but in a purely local sense of provenance. Thus, The Philosopher’s Pages presents a serendipitous encounter of local, intimate and personal remembrance, with a testament to the heights of intellectual speculation, that results in an unproblematic and serene memory of a complex figure whose posthumous fate is still undecided.

The case of Gentile is only but a particular manifestation of a more general trait – intellectual life, with all that it comports, does not extinguish itself with death, but rather, takes unpredictable turns and follows new plots, just like an ever-evolving fractal in the memory of the living.

Flaminia Incecchi is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of St

Andrews. She is working under the supervision of Gabriella Slomp and Vassilios Paipais on a dissertation entitled “The Aesthetics of War in the Thought of Giovanni Gentile and Carl Schmitt”. Her research aims at shedding light on the controversial figure of Gentile, and aims at establishing a conversation between Gentile and Schmitt. In doing so, she relies on several disciplines: history of ideas, aesthetics, political thought, and philosophy. She can be reached at: fi7@st-andrews.ac.uk.

2 Pingbacks