by John Raimo (July 2016)

As often as historians and art historians talk past one another, they also come together before common problems, questions, and sources. Both groups recognize the sheer power of images. Such a moment has reappeared in intellectual history. The recent one hundred and fiftieth celebrations of Aby Warburg’s birth underscored how widely Warburg’s terminology could stretch between art and cultural history. Historians such as Carlo Ginzburg and Patrick Boucheron take iconography as a starting point for deeper and deeper reconstructions of political and intellectual milieus. The work of art historians such as Georges Did-Huberman and Giovanni Careri follow similar patterns shuttling between contextual and formal considerations. Anthropologists too have not been far behind, finding in images the source for new methodologies across disciplines dealing with ideas both in and of history. And many museum curators do not shy away from presenting both ethical and historiographical challenges to the public in precisely this tenor, perhaps most spectacularly in the recent Conflict, Time, Photography exhibit at the Tate Modern.

Guerre 1939-1945. Occupation. Destruction de statues pour récupérer les métaux. La statue du marquis de Condorcet, homme politique français, par Jacques Perrin (1847-1915). Paris, 1941. JAH-REP-34-8

Four ongoing or recent exhibits in Paris also directly engage with the stakes that images—and specifically photography—hold for intellectual history today. Exhibitions dedicated to Seydou Keïta (1921-2001) at the Grand Palais, the photographers of France’s Front populaire (1936-1938) at the Hôtel de Ville, Lore Krüger (1914-2009) at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, and Josef Sudek (1896-1976) at the Jeu de Paume have this much in common: their images possess immediate documentary and historical charges, intervening histories challenge any recovery of the same, and the images themselves pose different meanings—political and otherwise—in our own time. How does one reconcile these knotty realities to one another, let alone relate them to questions of sheer aesthetic value, enduring or otherwise? Perhaps counter-intuitively, the question touches at once upon the artists themselves as much as upon each show’s respective curators. Together, they answer for the most part magnificently just how ideas and patterns of thinking flow into and out from photographs.

Perhaps no exhibit succeeds so brilliantly as that dedicated to the Malinese photographer Keïta. Self-taught and a portraitist by trade in Bamako, Keïta carefully arranges various customers against complex cloth backdrops in plain-light settings. Several layers of history collide in what only first appear as beautiful, if straightforward portraits. Keïta’s private practice runs from 1948 to 1962, shortly after Mali achieves independence from the French colonial empire. His customers find themselves at a crossroads: both women and men dress in traditional clothing as often as in European or American fashions, often modeling themselves upon the figures of the latest films and popular magazines. A watch ostentatiously displayed, a certain hairstyle, new western clothing, or certain postures together subtly betray consciousness of new cultural models, economic statuses, and social change ranged against Keïta’s brilliantly-patterned backgrounds. Both the circumstances of the photography session and the material object—the photo itself, as the exhibit makes clear—are intended to circulate by word of mouth and hand to hand. Yet an alchemical change also occurs. Keïta’s subjects prove subjects in every sense of the term; their glances say as much, even as they slowly come to look out upon a new country.

At the same time, a personal iconography emerges across the œuvre. Keïta’s workshop feature props (pens, glasses, flowers, and so on) that appear regularly throughout the portraits. An iconographic vocabulary similarly developed in the photographer’s carefully-choreographed poses. An uneasy sort of modernity can be teased out in the tension between these hugely personable figures, their clothing and possessions, and those objects and gestures which both they and Keïta saw fit to add to the compositions.

The art proves doubly-reflexive, looking inwards to the person and to life in Bamako as much as outwards to a rapidly changing Africa and globalization. Keïta’s own touch emerges in the gap. He arranges women into odalisque reclinings, organizes groups of civil servants into full profile portraits, and captures others at their ease wearing traditional clothing. The hindsight of a retrospective allows us to see how closely Keïta simultaneously engages European art history, the stock imagery of popular culture, and a Malinese society in transition throughout his career. The complex of ideas here reveal the subject much as the same ideas flow from the same person, the photographer himself, and finally the image in its own right.

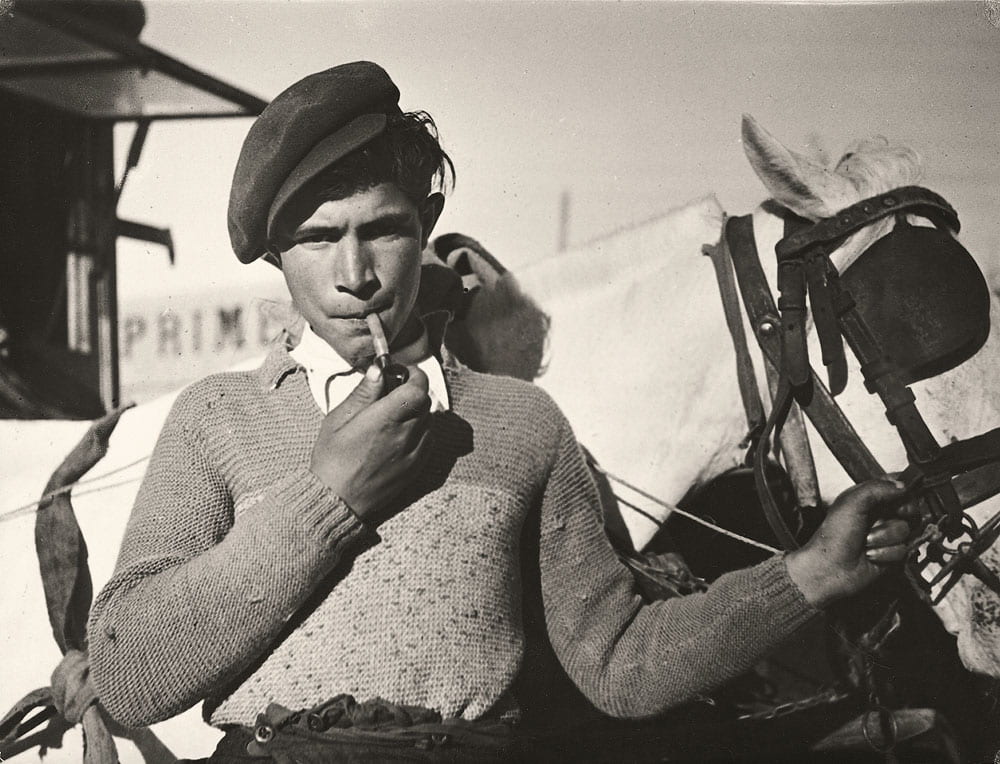

The Front populaire exhibition at the Hôtel de Ville attains a similar achievement, albeit on a different scale. The show follows upon a burst of renewed popular and academic interest in Léon Blum’s government and the period immediately preceding WWII. What emerges in the photos of such luminaries as Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Chim (David Seymour), Robert Doisneau, and Willy Ronis among other photojournalists is little less than a unified, if contested image of a society rapidly refiguring itself. Here technology proves the first hero. The portability of cameras, wide lens and higher resolution photography, and the ability to turn shots into next day’s paper gave birth to a new documentary language. Close-ups from within a crowd, odd angles, photos taken from rooftops hold their own with group portraits of politicians at ease in saloon lounges or mid-speech before thousands.

The great range or even discrepancy of Capa and company’s interests and work suggest a whole society falling at once under the same photographic lens, even as history jostles against advertisements and film stars in the daily papers. The photos appear on equal terms. Even publicity in the sense of public relations proves nascent, if not off balance. Airs of improvisation and the same-old business surround political figures like Blum and his contemporaries. Striking workers and public amusements achieve a glamour just as photographers accord the homeless and unemployed a new dignity. And slowly certain dramatic poses and compositions take on a new regularity across the exhibit. The vocabulary hardens and situations reprise themselves. New understandings of personal and sexual relationships, masculinity and femininity, and modernity itself track across the years. (One gentle criticism should be added here: it would have done well to have included far more female photographers.) What happens, as Michel Winock and others argue, is that French society comes to understand itself in images just as photographers came to learn their full historical potential—‘History’ with a capital ‘H.’

The German photographer Lore Krüger’s work confronts many of the same issues, if more obliquely. Her career and biography stagger the mind. Krüger studies photography with Florence Henri and other Bauhaus-trained photographers while attending lectures with László Rádványi in 1930s Paris, all the while absorbing the lessons of interwar avant-garde photographers (and living in the same house as Arthur Koestler and Walter Benjamin). An exile from Nazi Germany, Krüger passes through Majorca—witnessing Franco’s troops massacre Republican forces in 1936—and mainland Spain at the height of its Civil War before making her way to New York, where she and her husband work for the exile community’s German-language press. Giving up photography after the war, Krüger eventually returns to a quiet life as a translator and author in Eastern Germany before dying in 2009.

The exhibits’ curators posthumously assemble what remained of Krüger’s photography. In their composition, lighting, and psychological reach, her work achieves a uniform excellence across still lives, landscapes, portraits of friends, and above all in her studies of interwar gypsies. The balance between all her influences is remarkable, not least as Krüger too follows in the wake of glossy magazines and photojournalism. Yet a dichotomy of sorts also arises. For every ‘political’ image or photograph taken on the street, Krüger veers to high avant-garde experimentation elsewhere. These activities both overlap and command longer periods in her work, persisting until the end of Krüger’s artistic career. Something new emerges at the same time: what might be called the private lives of an avant-garde and an artist in wartime apart from any political engagement. The exhibit’s repeated argument that Krüger’s œuvre forms a consistent whole here seems to miss a much more interesting set of questions. How do we reconstruct private intellectual life, the persistence of international movements once contacts have been severed, and the experience of artistic experimentation continued under the hardest conditions?

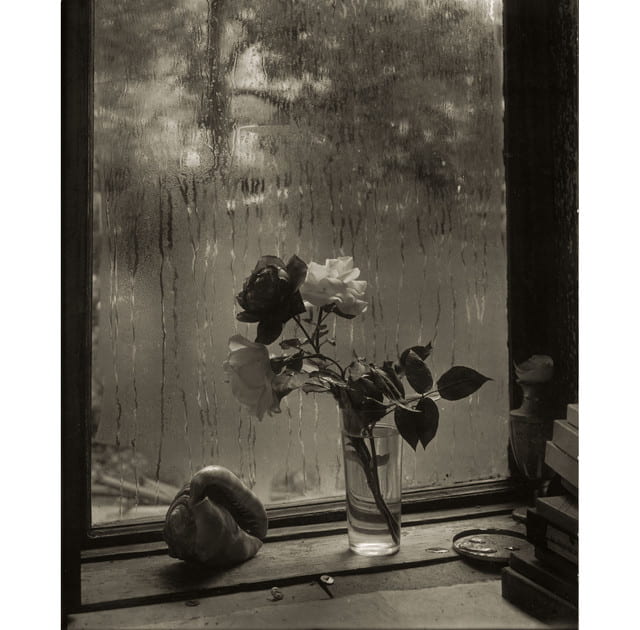

Josef Sudek, “The Last Rose” (1956, Musée des Beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa. 2010 © Estate of Josef Sudek)

All the same issues confront any attempt to wrangle the great, protean Czech photographer Josef Sudek into a coherent retrospective. The portraitist, the architecture and the landscape photographer, the artist of still lives, and the commercial man all jostle against one another over a career spanning the complicated histories of interwar and then communist-era Czechoslovakia. To reduce Sudek’s photography to any political (or apolitical) stance or simpler historical context would be a mistake on the same order of privileging one genre above the others. Yet the Jeu de Paume’s curators attempt something like this. Moving backwards from the interior studies, they claim a certain artistic unity which in turn drives the late Sudek into a sort of inner exile. An impression grows of intervening notions organizing a narrative: the late Romantic artist gradually finds himself confined to a window by the history beyond it, something like an uncritical reprise of Günter Gaus’s old notion of East Germany as a ‘niche society.’ This is not to say that the merits of Sudek’s work do not shine through the exhibit, or that the curators entirely mute his own thinking. The problem is rather that later ideas and contexts—historical or otherwise—drown out the images. As confidently as Keïta’s or as loudly as the Front populaire journalists’ pictures speak to audiences today, others such as Krüger’s and Sudek’s talk to historians, art historians, and all of us in much quieter tones.

Exhibitions reviewed: “Seydou Keïta,” Grand Palais (31 March to 11 July, 2016); “Exposition 1936 : le Front populaire en photographie,” Hôtel de Ville de Paris (19 May to 23 July, 2016); “Lore Krüger : une photographe en exil, 1934-1944,” Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme (30 March to 17 July, 2016); Josef Sudek : Le monde à ma fenêtre,” Jeu de Paume (7 June to 25 September, 2016).

October 19, 2018 at 6:53 am

This is a fascinating discussion of recent photography exhibitions! It is insightful above all on the historical texture of the image in different cultural contexts.