by guest contributor Anna Gialdini

In the Preface to the Magnum ac perutile Dictionarium (1523), Janus Laskaris put words into the mouth of his pupil Guarino Favorino about Favorino’s ethnic identity. Favorino argued that while his parents were Italian, he himself was Greek. ‘How, then’, he is asked ‘can you be Greek?’ ‘From the bottom of my soul,’ he replies, ‘My Greek studies serve as proof; […] I am a Greek within an Italian [body]’.

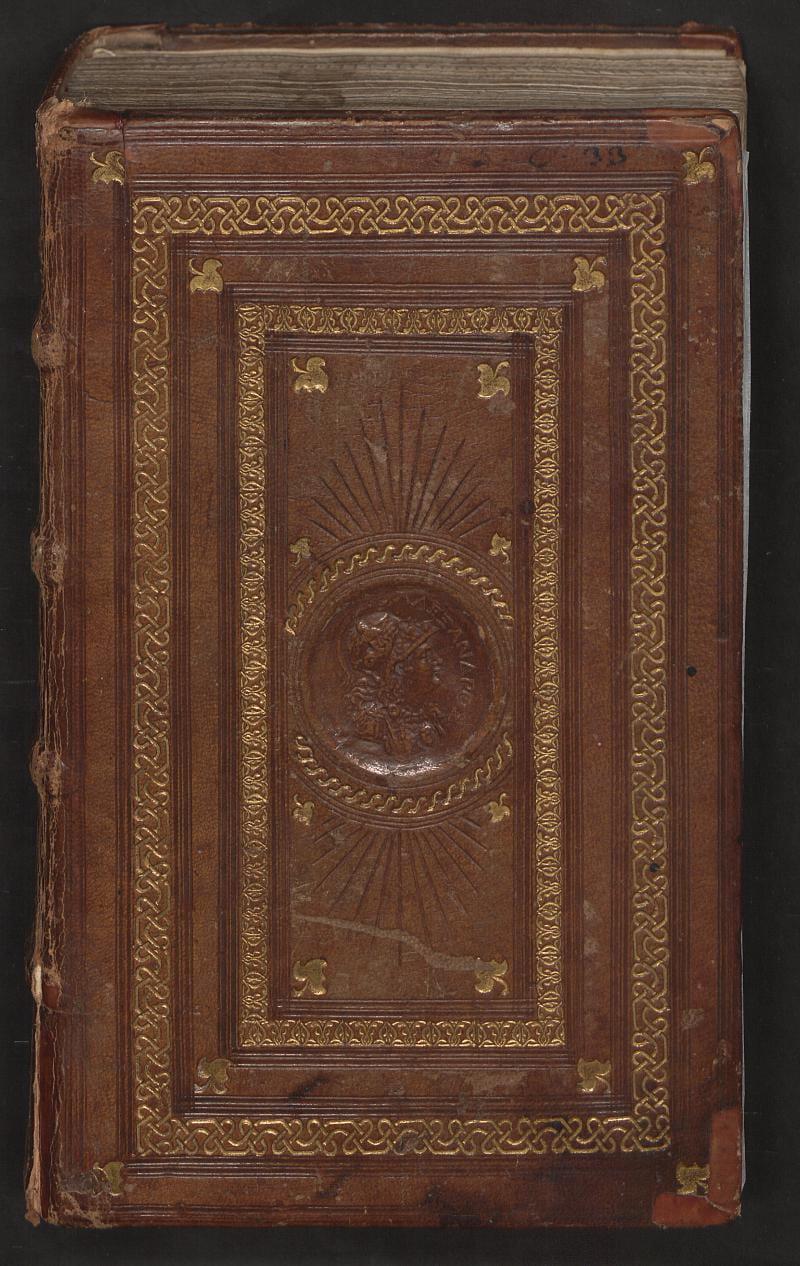

A copy of the Anthologia Graeca (1494) printed by Lorenzo de Alopa in 1494. Notice the raised bands on the spine, non-projecting endbands, and how the bookblock is smaller than the boards.

In Renaissance Italy, Greek studies became increasingly popular with the augmented availability of texts and teachers after the fall of Constantinople. Antiquarianism and Hellenism fostered collections of Greek books, programs at local institutions of learning, and patronage. Some scholars were content with reading, discussing, and speaking Greek. Aldus Manutius famously founded a Nea Akademia, the statute of which dictated that members were expected to only address each other in Classical Greek and those who failed to do so would be fined. Other humanists chose to don the Greek dress physically. While Janus Laskaris imagined Favorino in Italian garb, the Paduan Augusto Valdo, Favorino’s colleague in Rome, wore Greek clothes after an extended sojourn in Greece. The King of France, Charles VIII, liked to be depicted in Byzantine apparel, but for a very different reason: he nursed a dream of becoming ‘King of the Greeks’, as a popular prophecy of the time promised, terrifying the population of Italy during the turbolent years of the Italian Wars. He even bought the title off the last descendant of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI, Andreas Palaiologus, who died in poverty in Rome in 1502. Not that any power in Europe recognised the French monarchs’ sense of entitlement to the throne of Byzantium (in fact, both the Russian Tsar and the King of Spain thought the title would do nicely for them): but significantly, it does give us some hints to the different reasons why European élites came to look favourably upon ‘Greek’ objects. Identities came with a number of cultural and political implications, and what one wore, read, or owned could communicate them quickly and effectively.

One object that both scholars and men of power owned, and that ideally sits at the centre of the cosmos of ealy modern ideologies and culture, is books. Italians (and Venetians in particular, as Venice was home of the largest Greek community of the time) knew perfectly well not just what Greek men looked like, but also how to tell a Greek book from an Italian one. Venice was the largest hub for Greek books in Europe: most Greek texts were printed, copied, sold there, and brought over from previously Byzantine territories. It was also one of the main locales of production of Greek-style bookbindings, sometimes still called ‘alla greca’ (though the modern, if perhaps duller, but less ambiguous term for such bindings is ‘Greek-style‘).

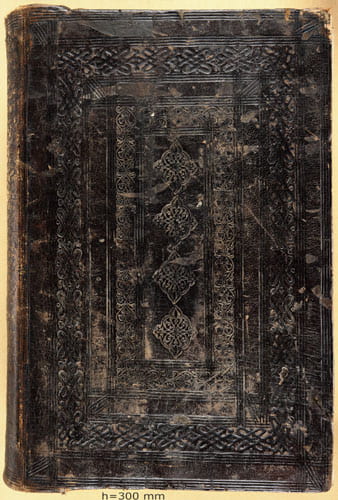

A Venetian-made genuine Greek-style binding on a fifteenth-century Greek manuscript (Milan, Biblioteca Braidense, Braid. AF.X.47)

Identifying how Greek a Greek-style binding made in Western Europe is can be tricky. In the last two years, I have surveyed over 350 Greek-style bookbindings (out of about 1000 surviving), most of them made in and around Venice. Around two thirds of the bindings are genuine, meaning that they replicate all the features of Byzantine bindings: (1) smooth spines given by unsupported structures, as opposed to spines with ridges given by sewing supports common in Western Europe from the Middle Ages onwards, (2) projecting endbands running along the edge of the boards, (3) bookblocks cut to the same size as the boards, as opposed to projecting boards, (4) grooved board edges, (5) and triple or double interlaced straps.

Bookbindings in which these characteristics are mixed with Italian, French, or other features, are called ‘hybrid Greek-style’. Plain genuineness and hybridism, however, are hard to come by. Even Byzantine bindings could lack grooved board edges from time to time, for reasons that are yet to be completely understood; and at the same time as Greek-style bindings became fashionable and then declined in Italy, Islamic, Armenian, and Western-European traditions were welcomed into Post-Byzantine binding practices.

In Greek-style bindings made in Italy, sometimes the individual components of a binding were the result of a mix between Greek and Italian traditions. Such hybridity could be intentional or merely circumstantial. Investigating structures and materials unveils all sorts of different situations in terms of agency, know-how, cultural contacts, and financial means. The binder might never have heard of Byzantine techniques before and not completely understand them, for instance. It is interesting to note that hybrid bindings seemed to be produced in most areas up to the turn of the sixteenth century. After the 1490s, there was a higher degree of sophistication, with bindings more genuine or more deceptively genuine-looking, at least in Venice. This coincided with the beginning of Aldus Manutius’s printing enterprise and the work of the only known Italian-based Greek binder who lived in Padua.

The funerary monument of Alvise Trevisan († 1528) in the Basilica di San Zanipolo, Venice). Note the Greek-style fastenings and the grooved edges of the boards. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

This corpus is only a fraction of what was originally produced, but it tells us that Greek-style bindings were sufficiently widespread that the intellectual elites of Western Europe knew how to tell them apart from other books. The Milanese philologist and physician Cesare Rovida, for instance, wrote to Gian Vincenzo Pinelli, one of the most famous Italian scholars and book collectors, that he was desperate to retrieve a manuscript of Aristotle that once belonged to Ottaviano Ferrari, his teacher and an acquaintance of Pinelli. ‘It is a folio size; in a fairly ancient script; […] the binding is not in the Greek style.’ (‘Non é legato alla \foggia/ greca, ma con altro modo’) (Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, MS S 107 sup., f. 8). Pinelli clearly knew what a Greek-style binding was; he owned six. The Mantuan Giangiacomo Arrigoni wrote a letter to Zacharias Kalliergis, requesting his copy of Hesiodus to be bound in the Greek-style (ἑλληνιστί), a rare example of a patron’s specific request in the bookbinding business. Greek-style bindings also make some appearances in visual sources and in inventories, another sign that they made a book memorable or an object of prestige. The library of Cardinal Niccolò Ridolfi included a printed copy of Lucian ‘bound in the Greek style‘ (‘ligato al greco’), and several volumes that belonged to Fulvio Orsini were also identified by their Greek-style bindings (‘ligato alla greca‘, passim).

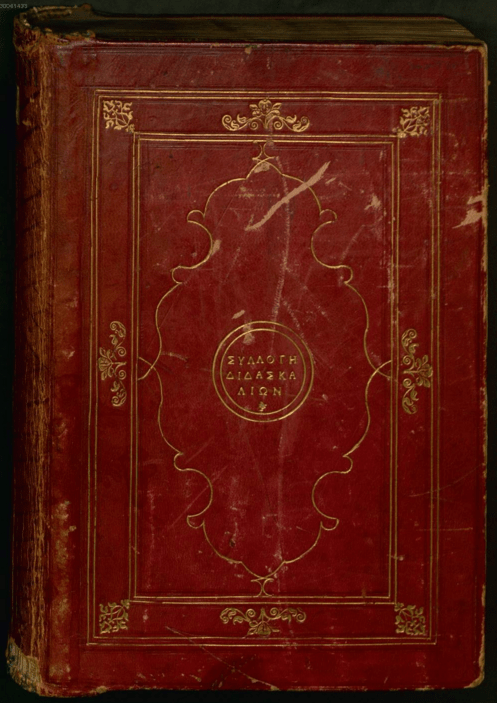

These individuals were high-profile scholars, and among the group of collectors who owned the most genuine Greek-style bindings that also contain Greek texts. They mostly had these bindings made in Venice. Johann Jakob Fugger also had hundreds of his manuscripts not only copied, but bound there. At the same time that he was leading the Fugger firm in the 1550s, he was also accumulating one of the largest libraries of his time, including approximately 300 Greek and Hebrew manuscripts bound in the Greek style (most of them genuine, with few exceptions).

MS Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod.graec. 61, bound in Venice for Johann Jakob Fugger.

Could Fugger read the books he collected so avidly and had bound so beautifully? He certainly was not an uneducated man; but it does not appear that he could Greek, much less Hebrew. A letter by his librarian, the philologist Hyeronimus Wolf, is often cited by German historians to support Fugger’s competence in the classical languages, but it only seems to confirm that Johann Jakob had mastered Italian, French, and Spanish in an impressively short time. An admirable feat, indeed: but no proof that he used his Greek books much.

On the other hand, the fact that Fugger has been remembered as a scholar for the past 450 years – that, in fact, many clamed that his insatiate hunger for books contributed to sending the family firm into bankruptcy – speaks clearly of the power of material culture. And it takes someone who is fully aware of the same intellectual strategies to challenge them. After enjoying Fugger’s hospitality in 1551, Roger Ascham (who would go on to teach the young Elizabeth Tudor her Greek) described his visit to his host’s library in enthusiastic terms, but accused Fugger of having no authentic interest in Greek texts or in sharing them with the rest of the world. No matter the allure of the bindings in his library, to Ascham Fugger was nothing but a βιβλιοτάφος, a ‘burier of books’.

Anna Gialdini studies Greek-style bookbindings in the Veneto in the fifteenth and sixteenth century at the Ligatus Research Centre at the University of the Arts London.

1 Pingback