By Contributing Writer Jeremy Glazier

When John Keats first looked into George Chapman’s rendition of Homer in 1816, he stayed up all night reading the two-hundred-year-old translation with his friend Charles Cowden Clarke and left us with a brief but white-hot record of that transformative encounter: a sonnet, composed on the two-mile walk home from his friend’s house in the wee hours. He was twenty-one years old, with four years left to live and nearly all of his important works yet to come. Cy Twombly (1928-2011) was also in his twenties when he discovered Homer, perhaps at Washington and Lee in 1949, or the following year at Black Mountain College under the tutelage of the poet Charles Olson. In any case, Twombly’s own artistic response to Homer would take longer to germinate than Keats’s—but when it did, it resulted in one of the most extraordinary works of art in the twentieth century: an epic ten-painting sequence, Fifty Days at Iliam.

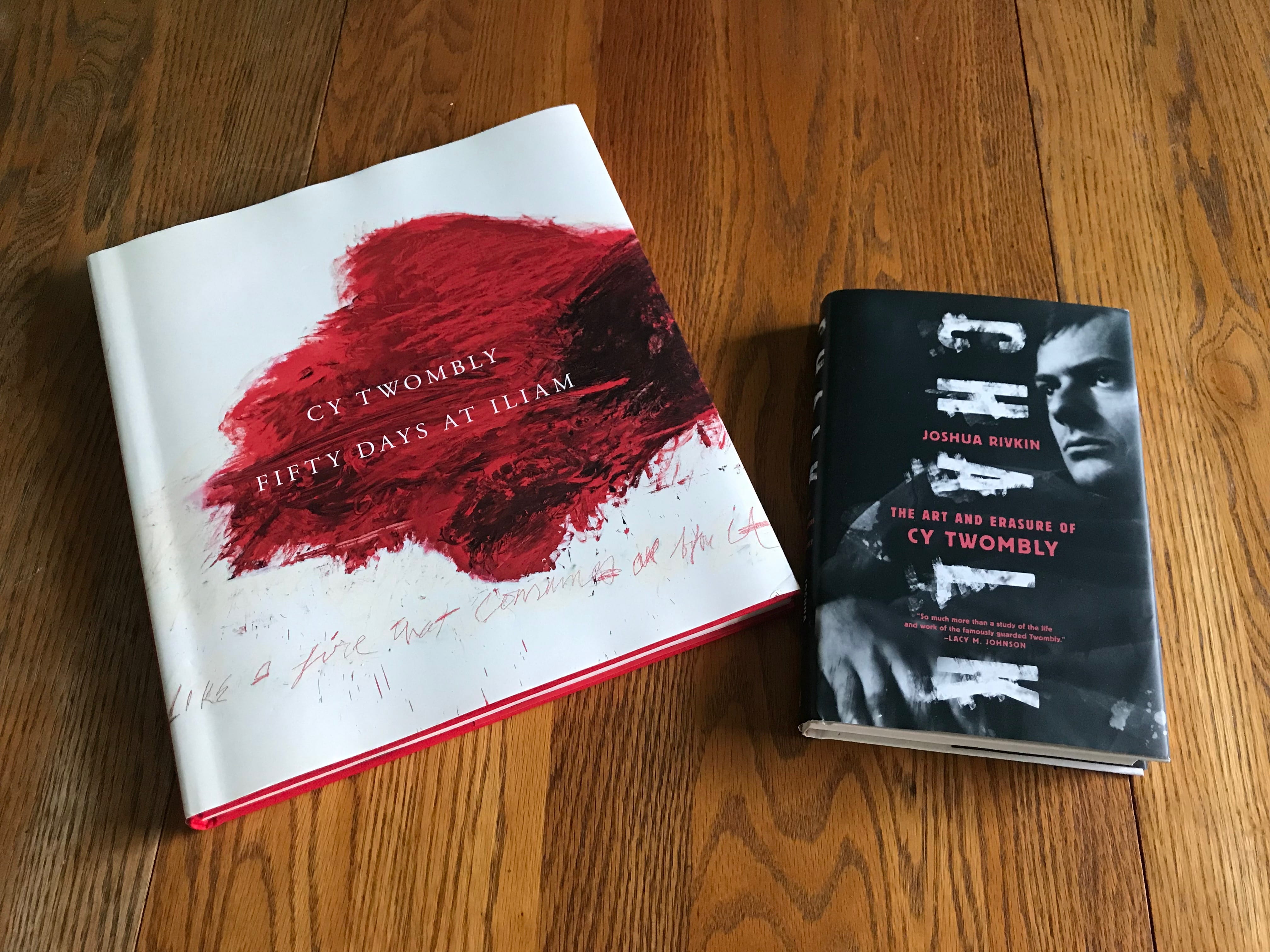

Two recent books on Twombly offer new insights into a sequence that Carlos Basualdo calls “one of Twombly’s most ambitious and successful works of art” (167). Basualdo is the Keith L. and Katherine Sachs Curator of Contemporary Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where the paintings have been housed since 1989, and the editor of the museum’s new catalogue, Cy Twombly: Fifty Days at Iliam (Yale UP, 2018). The book not only presents large, full-color prints of the sequence and many related works in the museum’s collection, it also gathers critical appraisals and commentary from art historians, classical scholars, and others. Twombly started work on the sequence in 1977 at the villa he had bought and restored in Bassano, Italy; he was fifty years old. Photographs of the house and Twombly’s studio, taken during this time, help to situate the paintings—which are also shown in their context on the museum’s walls—in the milieu that inspired them. As Joshua Rivkin has noted in another new book—published, coincidentally, the same day as the museum’s catalogue—these works “were as influenced by the interior spaces of Bassano” as they were by the Iliad (216).

Caption and credit for the headshot of Rivkin:

Joshua Rivkin Photo: © Mary Burge

Rivkin has written a compelling biography/memoir, Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly (Melville House, 2018), which weaves together the familiar elements of biography—the letters, journals, and ephemera that make up a life, compiled over the course of a decade—with Rivkin’s own metanarrative: his personal encounters with the paintings and with the people who guard Twombly’s legacy. Rivkin too has been to Bassano, accompanied by Twombly’s son Alessandro, to absorb the spirit of the place. Interspersed with his insightful commentary is another story, that of the writer chasing the shadow of his inspiration, trying to grasp the intangibles, make sense of something—call it genius—that’s not quite rational. In that sense, Rivkin is not unlike a translator: Pope or Chapman, seeking to transform one thing into another so as to be newly perceptible.

Rivkin, a poet, former Fulbright Scholar, and Stegner Fellow, takes a characteristically readerly approach to Twombly’s paintings: the canvases are texts to be read, texts that are themselves readings of Pope’s Iliad, which of course is a reading of Homer’s Iliad, which is a reading of one of the foundational myths of Western civilization. But “Twombly’s work resists an easy reading” (88), and Rivkin’s method, at once impressionistic and sharply focused, is not without its pitfalls: “in Twombly’s hand, one word can become another, and even scholars who spend hours looking mistake dreams for alarms, mistake one meaning for another” (89). The process of interpreting art, like the process of creating it, often isn’t rational. “Instead,” Rivkin explains, “I let myself experience them without trying to impose a narrative.” (80)

Yet narratives sometimes emerge anyway. The “cloud-like” red, blue, and white figures of Shades of Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector, the centerpiece of the sequence, “represent the dead heroes—these fuzzy ghosts, these spirits made flesh” (218). This painting—the one facing the visitor when first stepping through the gallery door—is for Rivkin the series’ emotional apex: “Death, these cloudbursts say, is waiting.” Other apexes appear in the form of the Greek letter delta (Δ), in red, which Twombly uses for the “A” in names like Achilles and Achaeans. Rivkin sees these not just as “triangles and names and phallic figures” but also as warriors “charging around the viewer in a frenzied rush” (217). There are no color plates in Chalk, unfortunately, but Rivkin’s readings of the canvases provides as intimate encounter with the paintings as can be hoped for in print—and a valuable supplement to the catalogue (or, better yet, to a visit to the museum).

In her essay “Adapting Homer Via Pope” in the museum’s catalogue, Emily Greenwood argues that Fifty Days at Iliam is “an important intervention in the history of Homeric translation and adaptation in the twentieth century” (73). As Olena Chervonik points out in “Study for the Presence of a Myth,” “Twombly’s artistic engagement with the ancient epic is not that of an illustrator, elucidating the twists and turns of a well-defined story” (90). Instead, he uses Homer’s “text as a springboard to dive into the complex history of the Trojan War.” Another word for that kind of springboard or intervention is ekphrasis. Usually we think of ekphrasis as a written, poetic description of a work of visual art, such as W. H. Auden’s famous “Musée des Beaux Arts,” with its comment on Breugel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. The classic example comes from Homer himself: the description of Achilles’s shield in Book 18 of the Iliad. But in the broader sense ekphrasis is the rendering of one art form into another, a sort of alchemy in which a work is transmuted from one medium into another.

In fact, The Shield of Achilles is the first painting of Twombly’s sequence, located just outside the main room in the Philadelphia museum where the others are essentially lined up for battle, Trojans on one side, Achaeans on the other. Twombly’s depiction of the shield represents a kind of meta-ekphrasis: it is a rendition on canvas of Homer’s famous depiction of the shield—though Rivkin argues that Twombly’s picture “is closer to Auden’s dark poem [with] its scenes of violence and nightmare, ‘barbed wire’ and ‘a sky like lead’” (217): in any case, a painting about a poem about a shield forged by a god as a cosmological map of the world. It’s practically a nesting doll of meaning, an omphalos awaiting skepsis. “In a way,” Rivkin muses, “Twombly always wants it both ways—to be figurative, calling forth the past, an invocation of a lost world and to have the gesture mean gesture. The line is the line.” (229)

Of course, it was Pope’s lines that Twombly’s work traces. As Greenwood notes, “Twombly ostensibly starts with a line of Homer, Englished by Pope […] and then in a process that both departs radically from and is consistent with the highly visual imagination of Homer’s traditional oral poetics, starts putting abstract lines to the war” (82). (Twombly owned a gorgeous copy of Pope’s translation, she relates in a note: an octavo second edition from 1720.) He also, according to Chernovik, “read and reread Homer in renditions from Roman times by Virgil and Apollodorus” and was familiar with Constantine Cavafy’s interpolations of Homer’s stories (89-90). Many of the twentieth century’s greatest masters turned to mythological themes for their muse—but few of them seem to have absorbed Homer’s text as fully as Cy Twombly did, particularly in Fifty Days at Iliam.

Cy Twombly: Fifty Days at Iliam and Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly (photo by the author for JHIBlog)

The two books taken together, then, present something like a master class in reading Twombly’s masterpiece: text, context, subtext, paratext. As Rivkin notes, “They are paintings to be seen all together, the drama of the whole, and to be observed one at a time” (216). Seeing the complete sequence in Basualdo’s catalogue’s high-quality reproductions is perhaps the next best thing to seeing them in sitio. The paintings and their provenance only make up a small portion of Chalk, but their story is at the very center—both literally and figuratively—of Rivkin’s indispensable book. Ultimately, he insists, the paintings represent “not Homer or Pope’s Trojan War but Twombly’s” (216). And thanks to these two very different but complementary studies, it’s now ours too, to read, to translate, to look at and into—perhaps with that same “wild surmise” Keats felt on first looking into Chapman’s Homer.

Jeremy Glazier is a poet, an essayist, and a two-time recipient of the Ohio Arts Council’s Individual Excellence Award in Criticism. You can read his essays on Alex Dimitrov, Don Share, Stéphane Mallarmé, and others in The Los Angeles Review of Books. His poems have appeared in Kenyon Review, Antioch Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, and many other journals. He lives in Columbus, Ohio and is Associate Professor of English at Ohio Dominican University. Email him at glazierj@ohiodominican.edu.

Leave a Reply