A Thought Experiment in the History of Travel

By Editor Spencer J. Weinreich

I seem to recall a history teachers in grade school telling us that in the Middle Ages, the average person never traveled more than seven miles from the place where they were born. The lazy stereotypes of a sedentary premodern population, and the concomitant stability of premodern communities and societies, have been thoroughly exploded (see, e.g., Gosch and Stearns): most magnificently by the Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta, whose journeys between 1325 and 1343 took him more than 70,000 miles, from Timbuktu to Beijing, from the Maldives to Gibraltar. Margery Kempe’s pilgrimages in 1413–18 reached as far as Jerusalem, Santiago de Compostela, and Rome. Far less exalted individuals—humbler pilgrims, merchants, soldiers, slaves—covered vast distances well before the age of steam, or even the so-called Age of Sail. Though he never achieved such extraordinary statistics or covered so large a portion of the globe, the founder of the Society of Friends, George Fox, displayed a wanderlust that stands on a par with Ibn Battuta’s. Born in 1694 in Fenny Drayton, Leicestershire, Fox traveled the length and breadth of England, Wales, southern Scotland, and southern Ireland, with trips to the Caribbean, North America, and mainland Europe, spreading his unique vision of Christianity.

I read Fox’s Journal this summer, while avidly following the by-election in Brecon and Radnorshire, held on August 1. An upset victory by the Liberal Democrat Jane Dodds reduced the Conservatives’ working majority in the House of Commons to one. In the months since, we have seen that majority evaporate entirely, the norms of British politics shattered and then the shards themselves shattered again, and finally a new general election, set for December 12. Week after week of parliamentary arithmetic, polling, and now campaigning—which I somehow feel compelled to follow—have warped my brain. And so I found myself wondering how many parliamentary constituencies Fox reached in his decades of travel.

Having perhaps too much time on my hands, I decided to find out. My principal source was Fox’s Journal, together with the accumulated knowledge of contemporary Quaker Studies. Some identifications were straightforward: in the course of his travels in the mid 1650s, for example,, Fox tells us, “Then we rode to Bishop-Stortford, where some were convinced; and to Hertford, where some were also convinced; and where now there is a large meeting.” The towns of Bishop’s Stortford and Hertford, Hertfordshire, sit in the aptly named constituency of Hertford and Stortford. In some cases, names had changed, or Fox refers only to the name of an estate or geographical feature, necessitating a bit of detective work. Consulting a map of British counties, I also attempted to infer his path of travel from what I knew of his itinerary: in the case of Cornwall, for instance, I knew that Fox reached St. Ives, at the far end of the South West Peninsula, in 1656. He traveled by land, and as the constituencies line up single-file, as it were, down the Peninsula, I could cross off Camborne, Redruth, and Hayle; Truro and Falmouth; and Newquay and St Austell whether or not the Journal specifically mentions them.

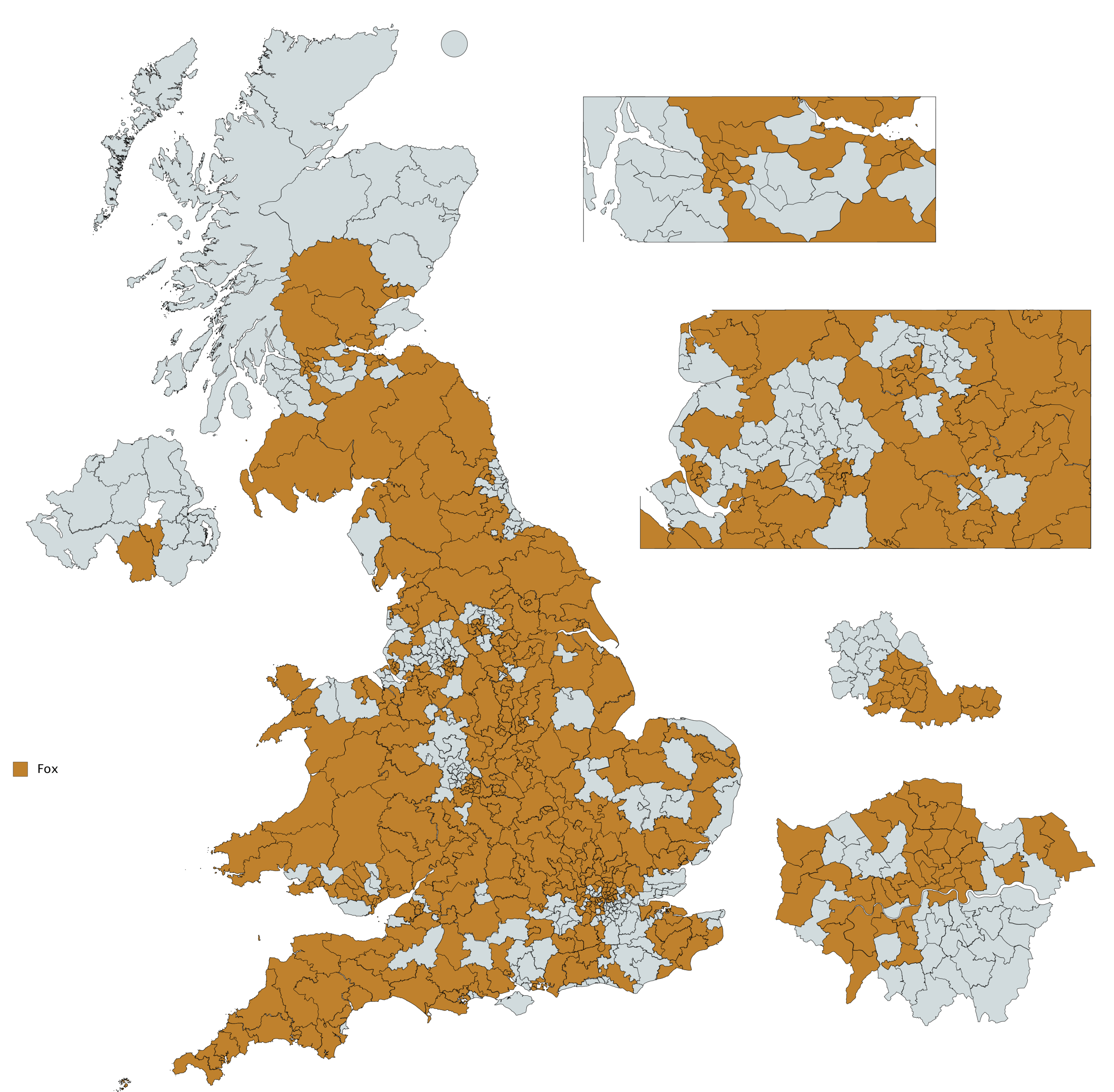

All told, I compiled a list of 408 constituencies (out of 650) that I felt reasonably sure Fox had visited. In modern British political history, that would constitute a historic landslide, second only to Tony Blair’s 1997 triumph (418 seats out of 659). It is possible that Fox would actually surpass Blair, as my list likely undercounts the Quaker’s travels through rural areas without named towns and through the greater London area. To take the most obvious example, Fox reached Liverpool by traveling through what is now Merseyside, but I could find no evidence as to the route he took, and thus which of the surrounding constituencies he passed through.

I was pleased to be able to “claim” Wycombe in Buckinghamshire for Fox: in 1698, seven years after Fox’s death, Wycombe elected the first Quaker, John Archdale, to parliament. In the event, Archdale could not take his seat, refusing—as a Quaker—to swear the requisite oath of allegiance to the king (William III). A duly elected Quaker MP was only seated in the House of Commons in 1832. Joseph Pease was chosen to represent the constituency of South Durham, but the same problem presented itself. A committee was appointed to consider the issue, which held that Pease could “affirm” his loyalty to William IV rather than swear it, an option that remains to this day for MPs of all faiths and none. South Durham was a sprawling county constituency, some of which Fox reached. Equally satisfying was finding that the two seats held by Quakers at the dissolution of the most recent parliament, the London constituencies of Hornsey and Wood Green (Catherine West, Labour) and Brentford and Isleworth (Ruth Cadbury, Labour) were both on my list.

An experiment like this, done with the rough-and-ready tool of an online map generator, comes with many drawbacks. The binary color scheme of my map—brown if Fox had reached a constituency, grey if he hadn’t—makes no distinctions of length or frequency. Newry and Armagh in Northern Ireland, which Fox visited briefly on his one trip to Ireland in 1669, is the same brown as Barrow and Furness in Cumbria, where Swarthmoor Hall, Fox’s home for the last decades of his life, stands.

For all that, the mismatches between Fox’s movements and the modern distribution of constituencies are instructive. The large numbers of grey constituencies in the southeast of London or clustered around Birmingham, Manchester, and Leeds indicate the dramatic increase in population and socioeconomic influence of those areas relative to Fox’s day, when there were fewer people to convince and fewer notable places to record in the Journal. Conversely, the wide coverage of what is now largely rural England and Wales reflects a far less urbanized and more evenly distributed population.

As a church historian, I must stress that the Society of Friends are in no way a political party, nor of any uniform political persuasion. To the contrary, the right and the duty to follow one’s inner light is at the very core of the Quaker tradition. Though West and Cadbury belong to the Labour Party, both entered the House of Commons in 2010 alongside Tania Mathias of the Conservative Party (Mathias represented another London seat, Twickenham, which Fox seems to have visited). Pease was a Whig, and most though not all of the Quaker MPs in the nineteenth century belonged to the Whigs’ successor party, the Liberals. In the European Parliament, Quaker Molly Scott Cato sits for the Green Party, representing South West England (a region well covered by Fox’s travels).

George Fox was met with derision, persecution, and physical violence wherever he went—not unlike many politicians these days. Yet he also found willing ears and many of the Meetings he founded are still active today. The distances he covered and the energy with which he worked would do credit to any candidate for office—and I suspect no party on Thursday will match the landslide victory I have dreamed up for him.