by contributing editor Brooke Palmieri

Even Thucydides, the celebrated father of historical realism, found it impossible to avoid revising the past in the telling of it. “With reference to the speeches in this history,” he writes in the opening to The History of the Peloponnesian War, “it was in all cases difficult to carry them word for word in one’s memory, so my habit has been to make the speakers say what was in my opinion demanded of them by the various occasions.” Dead men cannot verify the truth of the words put into their mouths. Which makes the past into something of a puppet show. Or at least makes history at its core a discipline shaped by desire, the desires we have to make sense of what has happened.

Some place greater demands upon and have wilder desires for their sources than others. Consider Voices from the Spirit World, composed by Isaac and Amy Post and published in Rochester, New York in 1852, a work which can only be described either as spectral historical revisionism, or social justice fan fiction.

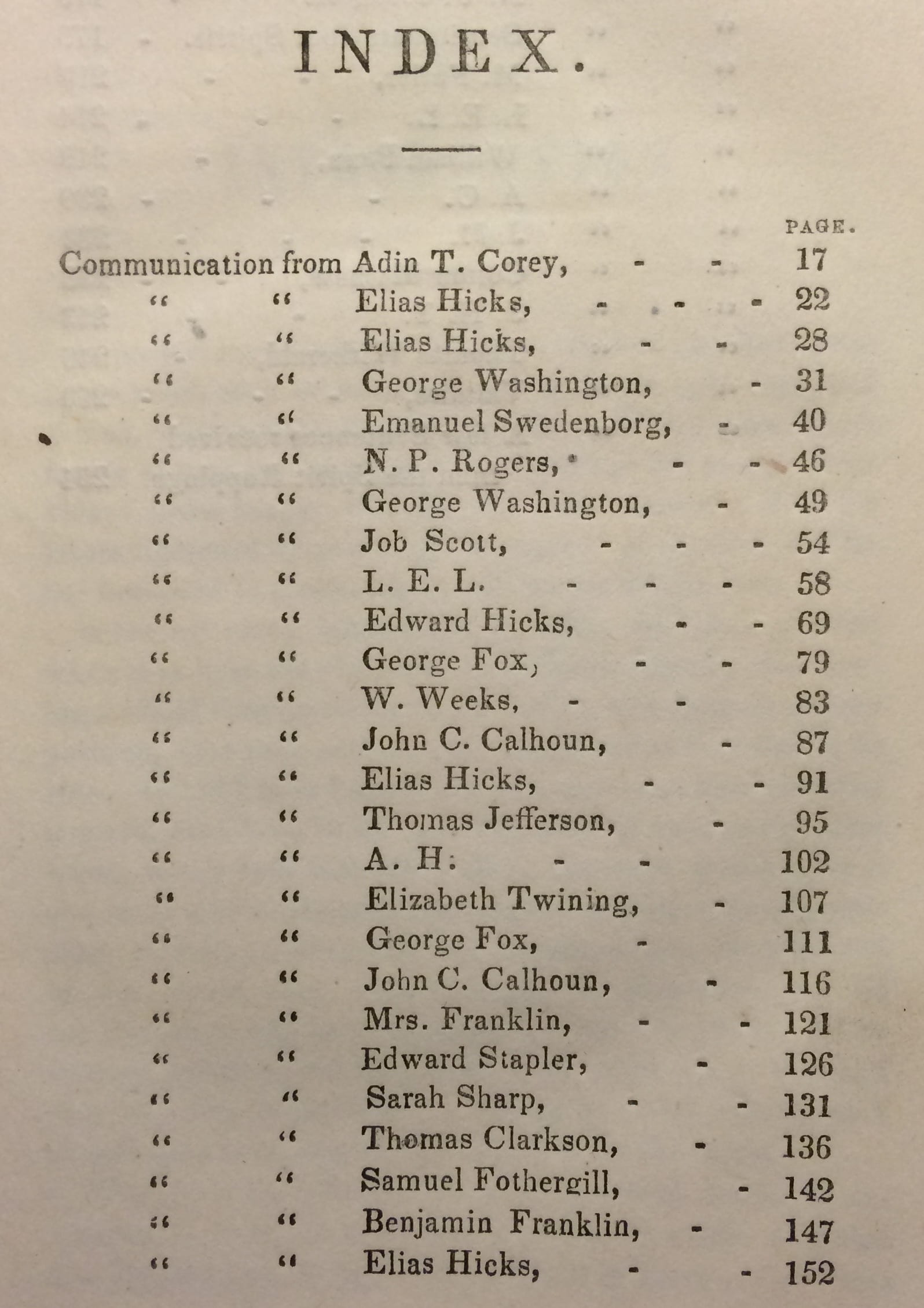

In it, the ghosts of famous dead people contact the authors, who then translate the “spirit rappings” they receive into a series of letters from the spirit world with advice for the living. “Benjamin Franklin” is the editor, who writes in the preface in typical Ben Franklin fashion that “Spirit life would be tiresome, without employment.” Franklin is also credited with contacting the other luminaries of public life, although Thomas Jefferson complains: “I find more difficulty in arranging my communication than when embodied.” The purpose of these spectral communications is, again, in typical Ben Franklin fashion, improvement. “Let no man claim that he has made great improvements in the arts and sciences, unassisted by spirit friends …. It is our object to spread light in the pathway of those who have been blinded by their education, traditions, and sectarian trammels. We come not to blame any; we present these truths, that man…may realize what he is, and what he is to be; to tell him by what he is surrounded.”

It is an incredibly literal way to enact the basic truth that history does offer precedents that can be built off of in the name of progress. But the aims of Voices from the Spirit World go deeper still: Franklin claims his purpose is that “death will have no terrors” for the living who are aware of the spiritual world. That is the best that the Spiritualist Movement had to offer: it was about facing death without fear, it was about ensuring that those who had died had not done so in vain, that their lives could offer wisdom and guidance in times of difficulty. The table of contents is a mixture of founding fathers, famous thinkers, Quaker leaders (the Posts were Quakers), close personal friends, and anonymous ghosts moved to speak.

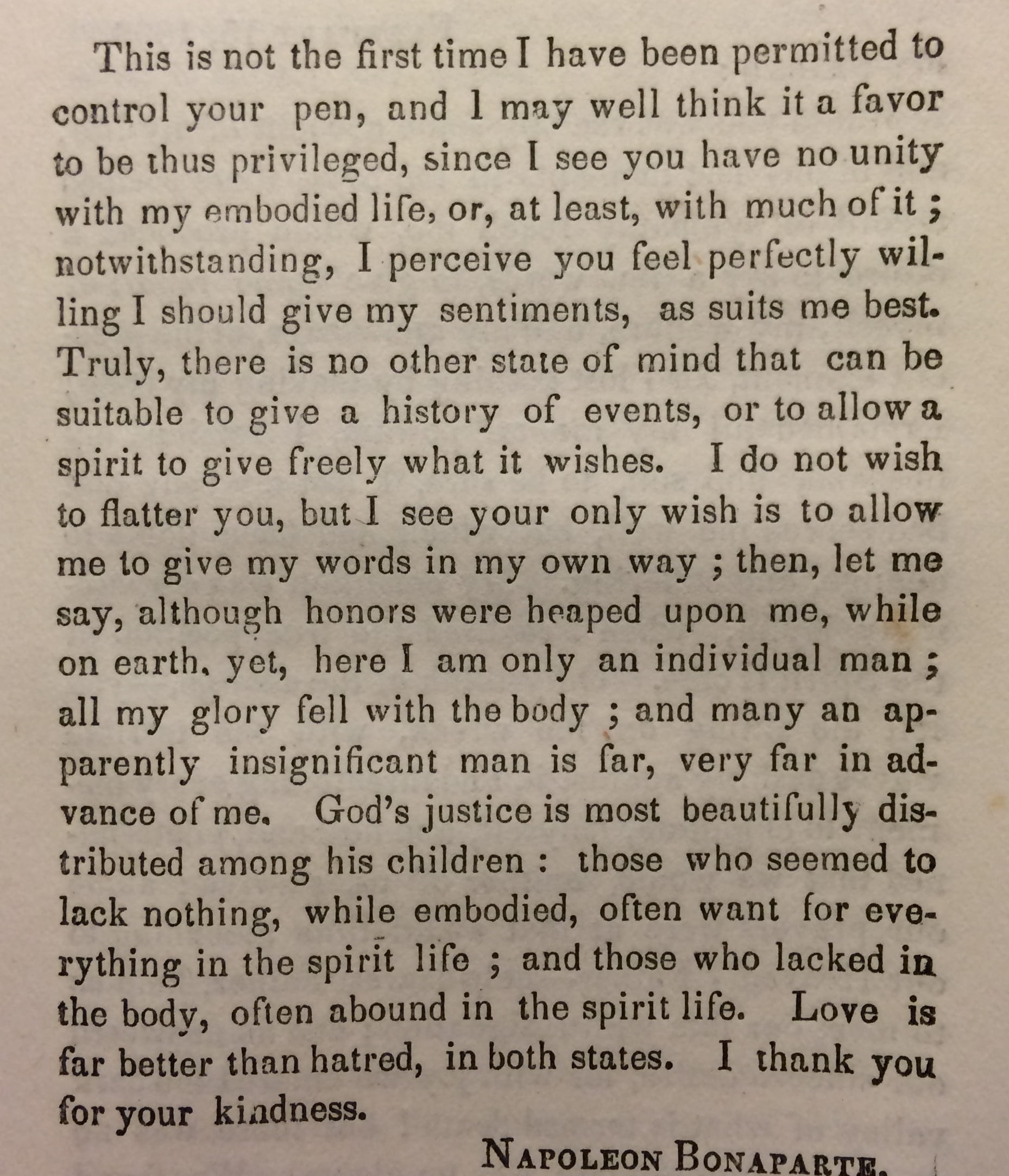

The “sentiments” each spirit leaves behind offer advice on a range of topics; Jefferson discusses political economy, Emmanuel Swedenbourg offers a lecture on magnetism, Voltaire oozes witticisms, Napoleon gives an account of “justice” in the afterlife that reads like a warning out of A Christmas Carol (1843):

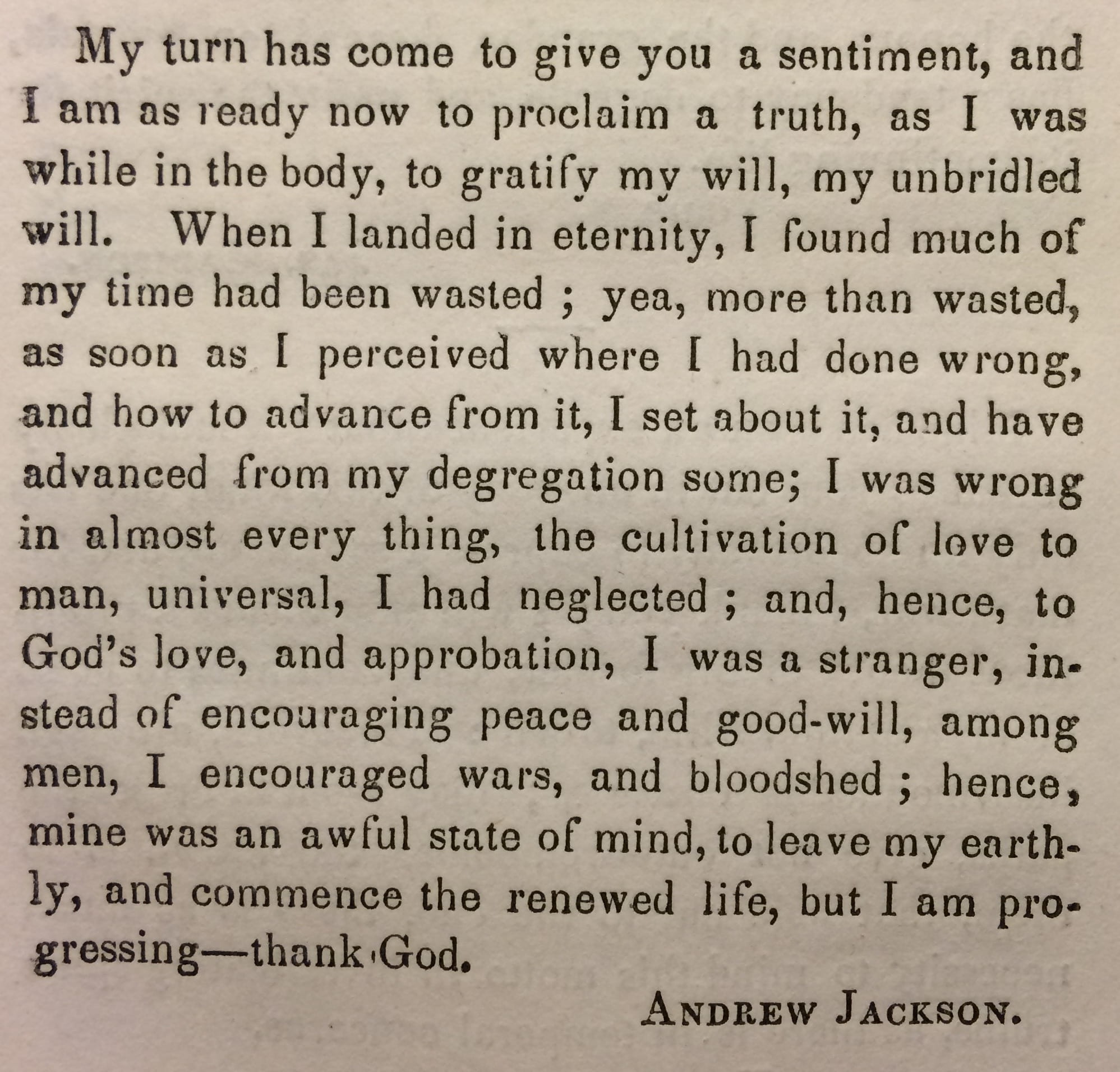

But overwhelmingly the spirits speak with one voice: they denounce war, the slave trade and women’s inequality from cover to cover. In a “Communication from G[eorge] Washington. July 29, 1851” the first president condemns slavery: “I regret the government was formed with such an element in it…I cannot find words to express my abhorrence of this accursed system of slavery.” A communication, surprisingly, from John C. Calhoun admits: “It is very unexpected to me to be called upon by Benjamin Franklin, informing that you desired to hear from me…It seems to me unaccountable that my mind should have been so darkened, so blinded, by selfishness, as to live to spread wrong, while I endeavored to persuade myself I was doing right.” Andrew Jackson publishes an apology for his entire life: “I was wrong in almost everything.”

Coincidentally, Isaac and Amy Post were passionate advocates for abolitionism, pacifism, and feminism throughout their lives. So it comes as no surprise that their dabbling in the spiritualist put spectral communication to work within the social justice movements they held dear, and this is what sets Voices from the Spirit World apart from other forays into spiritualism, which deal more expressly with grief and bereavement. The political nature of the work, the view of the other side offered by the Posts is nothing less than a utopia of ghosts.

There are no controversies, no “Sectarian Trammels” in the spirit world, there is no single religion that is better than others, no class, race, or gender-based inequalities. “It seems to me when spirit laws are understood,” Ben Franklin writes “every one will rejoice to be governed by them; hence the earnest desire that fills my heart to spread light before the earthly traveler.” So in place of a theory of progress that culminates, for Marx writing a few years earlier, in communism, the ghost of Ben Franklin would see the pinnacle of the living as submitting to the authority of the dead.

Yet for all its quirks,Voices from the Spirit World fits firmly within a tradition of Quaker publications dating two hundred years earlier to the 1650s, during the Commonwealth period in England. The origins of the movement were drawn from the revolutionary chaos of the English Civil War, and in common with other sects, the Levellers, Ranters, Diggers, Seekers, Baptists, turned their religious enthusiasm to the task of social reform: Quakers over the years advocated prison reform, education reform, gender equality, and racial equality. Particularly, Quakers in the colony of Pennsylvania committed to the abolition of slavery, with petitions against slaveowners (including other Quakers) being written in 1696, and throughout the 18th century until the movement came to a consensus on abolition around 1753, a story well told by Jeann Soderlund in Quakers and Slavery (1985).

The Posts were both Hicksite Quakers, a schismatic spin-off of the Society of Friends who followed the lead of Elias Hicks (1748 – 1830) in arguing that the ‘Inner Light’ (the presence of divinity in each human being) was a higher authority than Scripture. But this too is a more common fate for Quakers than simplistic histories suggest: controversy and schism was constant from the very beginning of the movement, and the ‘Inner Light’ was always a source of conflict, between Quakers and the government, and later between Quaker leaders and members. As a critic John Brown framed the problem in Quakerism the Pathway to Paganisme (1678): “we have much more advantage in dealing with Papists, than in dealing with these Quakers; for the Papists have but one Pope…But here every Quaker hath a Pope within his brest.” In Voices from the Spirit World, the Posts address this history of confrontation particular to the movement through various of its leaders: George Fox, William Penn, Elias Hicks, making them repent their fixation with schism: “O! What I lost to myself by my Sectarian trammels!” Hicks exclaims.

Voices from the Spirit World is less about the way in which we are haunted by history than about how relentlessly we might haunt the annals of the past, hunt the dead beyond their graves, draw words from their mouths to make meanings of our own circumstances and support our own causes. As Isaac Post writes in the introduction: “To me the subject of man’s present and future condition is of vast importance.” While the form of the book rests as a real limit case to historical revisionism, in spite of the absurdity there is an earnestness to the Post’s project that makes more rigorous and less utopian historical initiatives fall flat.

A special thanks to bookseller Fuchsia Voremberg of Maggs Bros. Ltd for bringing Voices from the Spirit World to the author’s attention.

December 14, 2015 at 9:08 pm

This is wonderful writing, Brooke! I want to ask whether there’s not an even earlier literary precedent rumbling around in the background as well. Here I’m thinking of the genre of ‘dialogue with the dead’ that Lucian invented and that runs right up in literary history to Enzensberger’s »Hammerstein oder der Eigensinn«. Granted, it’s more one-sided in more than one way in the text you explore above …. So, any ideas if there was a classical education or any sort of wider reading in literature behind this as well?

December 15, 2015 at 5:52 am

Thanks, John!

It’s excellent to link the Posts with Lucian’s legacy, and would probably require me to delve deeper into their lives & libraries to find the smoking book linking them to the classical tradition.

But in the meantime: Isaac and Amy Post were both raised within Quaker families, and while Quakers are often branded as ‘anti-intellectual’ the story isn’t that simple — Quaker schools trained their students VERY well, and in classic languages (at least, it was the case in Philadelphia). Quaker ‘anti-intellectualism’ was less about disparaging education than about disparaging the idea that you need an education to know right from wrong.

The most prominent element in the Posts’ lives was their activist work: for instance, they didn’t just advocate for the abolition of slavery, they provided a safe house on the underground railroad. They practiced what they preached to such an extent that it makes sense that their interest in spiritualism would be co-opted to their commitments to social justice.

And even if they believed that they really were being contacted by spirits, it amounts to the same: in recent times, ouija boards have been used in experiments to tap people’s unconscious reflexes. Or in other words, to find out what people know when they don’t *think* they are thinking. This article from the Smithsonian on Pearl Curran, a female author who wrote novels supposedly dictated by a 17th century woman, touches on the subject: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/patience-worth-author-from-the-great-beyond-54333749/?no-ist

That the Posts believed they were spirit mediums could just mean they were really, really consistent in their political convictions, from the unconscious on out.

But there is one final tradition of writing that I would still link this to within Quakerism: it’s the tradition of publishing ‘Dying Sayings’, supposedly speeches delivered on the deathbeds of Friends (and not just well-known members of the community). This also dates back to the end of the 17th century, and is a fictional, but realistic, way into describing the lives, experiences, and hard-earned wisdom of Friends, staged at the dramatic moment of their death. “Voices from the Spirit World”, which includes dispatches from many Quakers including friends of the Posts with no other publishing records, seems to push that convention of the death bed speech even further….into the afterlife!

December 15, 2015 at 5:53 am

Reblogged this on Bibliodeviancy and commented:

Brooke Palmieri covering the interwebs in clever, just like always:

December 15, 2015 at 7:46 am

Drew Faust gives a rich account of the wider rise of spiritualism in the 1850s in This Republic of Suffering, which shows that there was a wider national context as well, well before the Civil War gave these efforts to speak with the dead a new currency. But I’m convinced that the Quaker case is distinctive.

December 15, 2015 at 8:12 am

Thanks Tony…running to the library to supplement my knowledge in this field!

Because full disclosure: I had to keep the Posts isolated to their Quaker & social justice context as a matter of my own intellectual limits, not theirs!