By Jonas Knatz and Anne Schult

Stuart Elden is Professor of Political Theory and Geography at University of Warwick. His publication series on Foucault includes Foucault’s Last Decade (Polity, 2016), Foucault: The Birth of Power(Polity, 2017),The Early Foucault (Polity, forthcoming), and The Archaeology of Foucault (Polity, forthcoming). Beyond Foucault, he most recently authored Shakespearean Territories (University of Chicago Press, 2018) and Canguilhem (Polity, 2019). He runs a blog at www.progressivegeographies.com.

Jonas Knatz / Anne Schult: In both Foucault: The Birth of Power and Foucault’s Last Decade, you draw attention to Foucault’s own understanding of his work and argue that he wanted his books to function as tools and serve a purpose. You quote him saying that, “I make something that ultimately serves a siege, a war, a destruction. I am not for destruction, but only so we can pass, so we can advance, so we can tear down the walls.” (The Birth of Power, 187) The political effect of Foucault’s scholarship outside of academia is perhaps especially evident in the early 1970s through his involvement with the Groupe d’information sur les prisons (GIP) and Groupe d’information santé (GIS). In his lectures in 1982, Foucault further argued that the relationship to oneself is the final point to build resistance to power. How would you describe the trajectory of Foucault’s thought in relation to his political activism?

Stuart Elden: I think it depends on the period we are discussing. There is no doubt that the early-mid 1970s are the most political period of Foucault’s work – both in terms of the activism but also the focus of his teaching. There is little obviously political in this sense in his work in the 1950s or 1960s, and the later 1970s and 1980s is again distinct. The Prisons group has been widely discussed, and it’s great that Kevin Thompson and Perry Zurn are editing a set of translations of this work for University of Minnesota Press. That’s been the main focus of Anglophone scholarship. But the Health group seemed to me to be very interesting and less discussed, so I worked on that quite extensively for The Birth of Power. And there was more peripheral connection with another group on asylums, and various other political campaigns. Some of this work was archival, but there were a lot of published traces in sometimes obscure places – newspaper reports, some anonymous texts, some reports or brochures that hadn’t always been noted in bibliographies and so on. So, I set about tracking these down and trying to tell that story.

For me the two things that were most interesting about writing The Birth of Power was to treat this political activism in relation to the more obviously academic work, and to discuss the lecture courses from this period. I found it striking that Foucault could give a lecture at the Collège de France one day and later that same day, or week, speak at a press conference on prisoners or another contemporary theme. Defert provides a detailed Chronology of Foucault’s life and I used that as the basis for my own work, but I added in the dates of every lecture, every news report that specified what Foucault was doing, and made use of other sources like Claude Mauriac’s diaries. This helped me to read across these different registers of work – activism, lecturing, writing, and so on – and see some connections which I’d previously missed.

The more obviously political material appears in Foucault’s work quite abruptly. Foucault’s chair at the Collège de France was in the ‘history of systems of thought’ – it was effectively the history of philosophy chair, previously held by Jean Hyppolite, the Hegel scholar, and before him Martial Gueroult and Étienne Gilson. If you look at Foucault’s work before his election, it’s a series of historical studies – of madness, medicine and economy, biology and linguistics – along with The Archaeology of Knowledge and some other themes like literature and art. His first Collège de France course, published as Lectures on the Will to Know, makes sense as a continuation of that work. Now there are political elements in all that earlier work, and the founding of the Prisons group is during the first course at the Collège. But the 1971-72 course must have been quite a shock. Penal Theories and Institutions looks at a popular insurrection and its forcible suppression in the seventeenth century, and on the development of political and administrative structures in the Middle Ages. It’s really quite a contrast. In retrospect, when I wrote The Birth of Power I was perhaps reading that course and the subsequent one, The Punitive Society, with an eye more on what they led to, rather than where they came from. Now that I’m working on the 1950s and the 1960s in more detail, the contrast strikes me even more strongly. Yet again, though, there are continuities as well as contrasts.

JK / AS: In a 1984 interview with City Paper, Foucault said that “in the absence of anything better, I shall support the programme of the Socialists. I recall something (Roland) Barthes once said about having political opinions ‘lightly held.’ Politics should not subsume your whole life as if you were a hot rabbit.” Yet, the debate about Foucault’s political leanings and especially his stance towards neoliberalism and the welfare state has gained new momentum over the past few years. In an exemplary move, Daniel Zamora Vargas argued in an interview for Le Comptoir in 2019, reproduced in English by Jacobin, that in his later writings, Foucault “implicitly embraced their [Friedrich Hayek’s and Milton Friedman’s] representation of the market: that of a less normative, less coercive, and more tolerant space for minoritarian experiments than the welfare state, subject as it is to majority rule.” How would you describe Foucault’s take on neoliberalism and the welfare state?

SE: First, I want to say something very briefly about that City Paper interview. It’s a short text that wasn’t included in Dits et écrits, because it was published posthumously. The interview is brief – it was apparently reconstructed from notes, since Foucault didn’t want to be recorded. Foucault would have either refused its publication or edited it himself had he lived. It took me a long time to locate a copy. I was in touch with the interviewer, and he said he didn’t even have one himself. It’s not clear whether Foucault spoke in French and was translated, or in English – quite possibly a bit of both. And that line about a ‘hot rabbit’… Foucault obviously means a chaud lapin, which is of course literally a ‘hot rabbit’, but is more a rabbit in heat, a horndog or something of that kind. But we don’t have the ability to either see a French original or know what Foucault said – whether in his own English expression of a French term, or a too-literal translation. This is a minor example of something I found really frustrating when doing this work – how much had been lost. Transcriptions of recordings, tapes, original manuscripts and so on. And this is for the 1980s, when Foucault was already very famous. It’s much more the case for earlier material when there was no obvious reason to keep things.

But to turn to the question. I have found the whole recent neoliberalism debate about Foucault very frustrating. There are obviously things to be said about how in 1978-79 he gave the course The Birth of Biopolitics which discusses this work. But it’s a historical study for the most part, even though it is Foucault’s most contemporary course. In the story I try to tell, Foucault turned to this period as a continuation of the historical work in the preceding course, Security, Territory, Population. He’s interested in this question of government in a broad sense – of people, groups of people like a flock in the Christian pastorate, or of a family and so on. And the more narrowly political sense of government relates to and emerges from that. And then in this course, Foucault connects it to a much more contemporary set of practices. My reading is that he is trying to understand these trends, their internal logic and core assumptions, rather than to come down in favour or against. In a sense it’s only because it’s so contemporary that Foucault is seen in this way in relation to neoliberalism. I’ve made the point before that in the previous year he was analyzing the raison d’état theorists and in the next the early Church Fathers, and with those bodies of work there isn’t the rush to suggest he was in favour or against. So, I don’t really see Foucault either as a fellow traveler of neoliberalism, or as its more prescient critic. Obviously where things were in early 1979 isn’t where they went – Foucault was lecturing before Thatcher or Reagan were elected, and French context was quite different.

The other thing I’ve found frustrating is that much of this work has simply reread the available material, rather than dug into the archives for other related materials. There seems to be much more that could be done interrogating Foucault’s interest in this—what happened in his Collège de France seminars around this time, which were around liberalism and government, what were the people who presented in those doing, how does this connect to manuscripts he wrote at the time, and so on. But for the most part I’ve avoided engaging with the debates about this topic, since I think in large part they are beginning from a too-easy elision between his historical approach and a contemporary political problem. Foucault was always much more circumspect.

JK / AS: In both published books, you heavily draw from Foucault’s less formal output, such as the materials he produced in preparation for and aside his lectures and seminars at the Collège de France. What does this focus on unpublished notes allow you to see that otherwise has stayed hidden? To what extent does this information reframe well-known tomes such as Discipline and Punish and the History of Sexuality as thought-in-progress? And how do you see your work relating to Foucault’s lectures themselves, which have been published in book form by Gallimard since the 2010s under the general editorship of François Ewald and Alessandro Fontana?

SE: Foucault’s lecture courses have been invaluable to my work. I wrote my PhD on Nietzsche, Heidegger and Foucault, and the first lecture course to be published, Society Must Be Defended, appeared in French in 1997, towards the end of that period. Dits et écrits appeared in 1994, right as I began working on the thesis. Dits et écrits was the initial spur to do something that looked at Foucault beyond the books, since as well as collecting hard-to-find sources in French, it also translated texts from Japanese, English, German, Portuguese, and so on. It then took 18 years from Society must be Defended until Penal Theories and Institutions, the last of the Collège courses to be edited in French in 2015. I wrote essays, reviews or gave talks on many of the lecture courses as they came out – Paul Bové at boundary 2 was an initial supporter of this work – and so when most of them were out I had a good sense of the material and thought this could be the basis for a study that used them to fill in the details of his work.

Alongside the lecture courses, more and more other material became available – we’ve already discussed some of it. I try very hard to respect the differences in genre between a published book, an interview edited and approved by Foucault, a lecture edited from a recording, student notes, archival traces and so on. But reading these different types of work together can, I think, be revealing. Among other things it shows the paths not taken—projects planned and abandoned, initial formulations which were later reworked as he found new sources or inspirations and so on. The reading notes he took when he was doing his work were valuable in writing The Birth of Power, and more so for the work on the 1950s. They show something of how he worked—of notes or excerpts from what he was reading, thematically organized—and then used as the source material for his books. There are not that many early drafts of his published books—I’ve mentioned the ones of the second and third volumes of the History of Sexuality, and there is a complete and a partial draft of The Archaeology of Knowledge. But while Foucault may well have destroyed some draft materials, he also reused them. There are quite a lot of pages of notes which are written on the reverse of a text with a diagonal line through it, and often those are fragments of well-known texts. He reuses other things in his folders too—sometimes folding a letter or a flyer to group notes on a theme. Given Foucault dates almost nothing, these scraps can sometimes help to indicate a period when notes were taken. Foucault’s use of scrap paper is a project in itself.

So, I think the reading notes, and other preparatory materials give some sense of how Foucault worked, and of things that might have been pursued and, for whatever reason, were not. I try to discuss all of that in the books I’ve written. Ultimately the books outweigh them, of course, but treated appropriately the lectures and other sources can be valuable supplements.

JK / AS: Emphasizing the collaborative nature of some of his projects in the context of his seminars at the Collège de France, especially in the lead-up to Discipline and Punish, or his work with the Centre d’études, de recherches et de formation institutionnelles (CERFI), you appear to argue that Foucault was significantly shaped by and indeed sought the interaction with other like-minded scholars. Which of his myriad collaborators do you see as most significantly influencing the Foucauldian project, and does the allowance for a more collaborative background in any way reframe some of Foucault’s oeuvre?

SE: Yes, I think the collaborative nature of Foucault’s working practice has been underappreciated. He really seems to have enjoyed the collaborative process, though he found some of the restrictions frustrating. At the Collège de France he wanted to restrict his seminar to those who were genuinely going to do work, rather than just consume it. But the authorities didn’t allow this, and apparently tape recordings were made of discussions and pirate texts were circulated. Eventually he got so fed up he cancelled his seminar and gave more lectures to meet his quota of hours. That said, one of the frustrations I found in working on this period was how little there was as a record of what happened in the seminars. The I, Pierre Rivière collection was one output from Foucault’s seminar, and some other papers first presented there were included in The Foucault Effect. But Foucault usually said what the seminar did in his course summaries each year, and some of that fed into the CERFI research. The first archival work I ever did on Foucault was looking into that research around 2004, using the archives at IMEC—at the time in Paris, but now in Normandy. There were various reports published, some of which are quite hard to find these days, and some texts in the journal Recherches. There are later collaborative seminars, some of which have been published—the ones at Vermont and Louvain ran in parallel to lecture courses, and there was the beginning of a project at Berkeley cut short by Foucault’s death. But other people in those seminars did publish their parts of the work. I tried to speak to some people involved in this work, and find what traces there were—this led to the publication of a discussion between Foucault and Jonathan Simon, for example. There are other important reports in the History of the Present newsletter that Paul Rabinow edited. Foucault didn’t co-author many published texts—the book with Arlette Farge is perhaps the key exception—but he worked with people quite a lot, and not just in his activism. I try to tell these stories in the books I’ve written.

Some of those he worked with are well known as thinkers in their own right – Deleuze and especially Guattari for the CERFI work, for instance. Foucault’s work with Deleuze and Pierre Klossowski on the Nietzsche translation project is a story I want to research, as is his involvement in the Georges Bataille Oeuvres complètes. In an earlier period, his work with Jacqueline Verdeaux is very important. Farge is a major figure in French history, but was of a later generation to Foucault when they worked together. Foucault seems to have appreciated the work of some of his Collège de France colleagues like Pierre Hadot and Paul Veyne, though they didn’t collaborate in the traditional way. And the group of students Rabinow introduced him to at Berkeley would, I think, have been key interlocutors had that work not been cut short.

JK / AS: Similar to Foucault, you often invite commentary on your current work through your blog, Progressive Geographies. Here, you discuss your research process in detail and share insights on sources and tentative analyses. How do your book projects benefit from this openness and the interaction with your readers? Does this approach ultimately serve as an attempt to “demystify” intellectual history, which is often assumed to be a solemn enterprise?

SE: As with much of what I’ve done on the blog it’s been something of a trial and error process. I never imagined the blog would get the audience it has – still small certainly, but relatively large for an individual academic blog. And so, some of the things I’ve done on the blog began as things I thought would be interesting for me to do, rather than with an expectation of a large audience. One of the things that I’ve enjoyed doing is these posts on the process of writing these books. I’d stress that part – I write about the process of doing the research, rather than sharing draft material. Other people share work in progress, and I follow some of them and find that fascinating too. But I think what I do is different. I have been writing updates on the work since I began these Foucault books, though I began this a bit earlier in the late stages of writing The Birth of Territory in late 2010 and early 2011.

So, I write posts saying – this is what I’ve been reading, this is how I’ve tried to make sense of it, this is what I found in the archives, libraries and so on. I don’t get a great deal of feedback this way, actually, though there is, I think, sufficient interest in the work to make it something I have continued. I’ve also shared quite a few ‘resources’ as webpages on the blog – things I’ve produced as research tools for myself in doing this work, but which end up only being explicit in the finished book in a very minor way. So, I’ve done textual comparisons, for example, where I’ve compared two versions of the same text to see what the changes were. That’s slow work, but often I found it necessary to what I was doing, and yet in the finished book it perhaps only informs a couple of notes. Or I’d translate a short text or excerpt and then only quote a sentence or two. So, I’ve shared those on the blog in a hope that perhaps someone else might find them useful. Or I’ve made a chronological list of links to all the Foucault audio and video sources I could find online and shared that. Most of these are things that couldn’t be published in a normal way – though I did publish one bibliography of short texts by Foucault that were not in Dits et écrits – so I thought using the blog would be one way to make this material available. The blog or website format works well – I can post it immediately, and edit if new sources come to light. Again, I’ve not had a huge amount of feedback, but a couple of people have got in touch to share something they know – one former student transcribed his notes from a lecture he attended, and alerted me to a variant form of a well-known text that I’d missed. A couple of other people gave me access to recordings they had, one of which was not previously widely known so I shared it with the editors of Foucault’s work. So, I think this work has been useful to me in part through my becoming a minor point of connection in the circulation of texts. One of the editors got in touch with me as they thought I could answer a quite specific question, which I was able to do, and that led to some other meetings and sharing of material. In my research I have been continually pleased by how helpful people are when I ask for things – not always, but certainly most of the time. Perhaps what I do on the blog is one way of paying that back.

I’m in a Politics and International Studies department, and yet I find the debates I’m most interested in are happening in other circles, philosophy naturally, but also in history and other fields. The blog is one way of connecting to them, as indeed are invitations to speak in different places. I often share those talks too on the blog – partly as a way of building up a personal archive, but also in the hope someone will find them interesting. It’s so easy to record a talk on a phone, and I use an open source audio editor to tidy up the start and finish, normalise the volume, cut out any extraneous noise and so on. If I didn’t share them, then I probably wouldn’t have the discipline to do that.

That’s a long way of saying that the blog is a way of sharing what I’m doing, but not yet the final or even draft form. I hope that when The Early Foucault comes out there will be plenty of surprises to people who’ve been following the blog updates. I reread something I wrote just a couple of years ago the other day, and I found myself disagreeing with quite a lot. That’s simply a measure of how much I’ve learned in exploring this period, and how much previously I was relying on the standard story. But yes, perhaps I have demystified the process of writing these books. It’s also a way of connecting to a wider audience, and to people in different parts of the world, some of whom I know but rarely see.

JK / AS: Out of the many potential surprises The Early Foucault holds in store, are there some that you would be willing to share or hint at?

SE: In the 1950s Foucault doesn’t publish very much – the short book Maladie mentale et personnalité, a long introduction to a translation by Ludwig Binswanger, two book chapters and a brief book note. But he writes a lot more than this. His diploma thesis on Hegel from 1949, supervised by Jean Hyppolite and long thought lost, has recently been found. There are three substantial manuscripts preserved in Paris, as well as a number of shorter texts. The three major manuscripts, all of which are due to be published in the next few years, are on philosophical anthropology, Binswanger and existential analysis, and phenomenology and psychology. The first of these is a lecture course, probably first given in Lille and then later at the Ecole normale supérieure (ENS). It discusses anthropology as the science of man, including figures such as Kant, Hegel, Dilthey and Nietzsche. The other two may have had their origin in teaching, but are fully written out manuscripts with notes, and seem to have been intended for other purposes, perhaps as theses. The Binswanger text is much more substantial than the published Introduction; the phenomenology course shows Foucault had a really detailed knowledge of Husserl, who is the main focus. I discuss all of these texts in the book, and try to build up a picture of his wider teaching from the extant materials in Foucault’s own archive, along with the notes preserved in other places by a couple of his students.

Foucault’s role introducing Binswanger translation is quite well known, but while he wasn’t credited as a co-translator, he did work closely with Jacqueline Verdeaux on the text. So, I provide a detailed discussion of the choices they made to render the German into French, which I also do for the translation Foucault did with Daniel Rocher of Victor von Weizsäcker’s book Der Gestaltkreis. And in a later chapter I do the same thing for Foucault’s translation of Kant’s Anthropology, which was his secondary thesis in 1961, along with a long introduction. In the first chapter I discuss Foucault as a student, looking at the courses he attended by people like Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean Wahl and others, and his preparation work for the agrégation examination. He worked closely with Louis Althusser for this at the ENS, and Althusser’s papers include some notes on practice presentations Foucault gave. Foucault’s reading notes on psychology, philosophy and other themes are also preserved—some very clearly preparatory for publications including the History of Madness; others are more general including the extensive notes on Nietzsche and Heidegger he talks about in a late interview. Reading these helps to make sense of how Foucault engaged with these thinkers, as well as something of how he composed his texts.

I also went back through Swedish newspapers to reconstruct the titles of public lectures that Foucault gave in Stockholm in the mid-1950s. The lectures themselves have not been preserved, but the titles at least give an indication of their content on French theatre and literature. The topic of his teaching in Uppsala can be found in the University course catalogues, but again, nothing seems to be preserved. One text that does exist from this period was given as a radio lecture in Berlin, and the German translation of that text is in the Swiss literary archive in Berne. It’s on anthropology, with a discussion of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and Claude Lévi-Strauss, but also of Georges Dumézil, whose work Foucault was beginning to read in detail.

The main source for this book is the BnF archive, which as I said contains not just the papers left in Foucault’s apartment when he died, but also materials he left at his mother’s house, probably before he moved to Uppsala in 1955. I try to integrate the study of all these largely unknown materials with the things he published in this period, and to fill in details that the biographies were sometimes only able to survey. But I’ve also used quite a few other archives to track down other sources that might shed light on this period – from the papers of Foucault’s teachers like Althusser and Wahl, to his doctoral rapporteurs Canguilhem and Hyppolite, and of Binswanger and Roland Kuhn. I try to say something about the intellectual side of Foucault’s relationship with the modernist composer Jean Barraqué. Books given to Foucault are at Yale, and there is some correspondence in other places. There are some papers in Uppsala relating to his time there, and Melissa Pawelski did some valuable work for me on his time in Hamburg, which has been extensively discussed by Rainer Nicolaysen. These cultural and teaching postings, along with his time in Warsaw, are important parts of the story I try to tell. So, it’s a book that begins when Foucault moves to Paris as a student, and ends with the History of Madness—a period that many books on Foucault see merely as a prelude.

***

This is the second installment of a two-part interview with Stuart Elden about his work on Michel Foucault. Read the first part here.

Jonas Knatz is a PhD Student in New York University’s History Department. He works on 20th century European intellectual history.

Anne Schult a PhD Candidate in New York University’s History Department. Her current research focuses on the intersection of migration, law, and demography in 20th-century Europe.

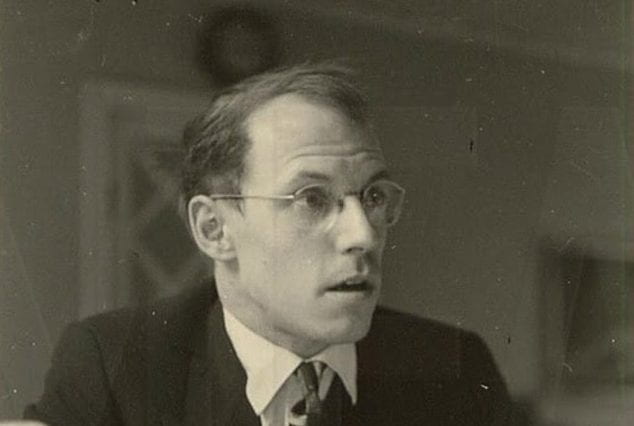

Featured Image: Michel Foucault in Uppsala in the late 1950s. See also the cover of Lynne Huffer’s Mad for Foucault: Rethinking the Foundations of Queer Theory.