By Luna Sarti

Probably the most hated weed in North America, dandelion has over the past couple of years secured a space on the shelves of “premium retailer” grocery stores, such as Wholefoods and Sprouts Farmers Market. Having grown up eating dandelion greens, I am certainly grateful to Wholefoods for validating my weird commitment to treat “weeds” as valuable plants which I protect in the lawn. Week after week, as I observe homeowners in my neighborhood invest energy, time, and money in the Sisyphean enterprise of lawn maintenance, I delve deeper and deeper into the history of dandelions: when did dandelion become a weed, and why is now the time for its shifting back into “a specialty food”?

In 1990 Peter Gail, known as the “King of Dandelions”, published The Dandelion Celebration: A Guide to Unexpected Cuisine – an attempt to change the perception of dandelions and prompt the American public to recognize them as food. Dr. Gail, who earned a Ph.D. in Plant Ecology from Rutgers University and was Associate Professor of Urban and Environmental Studies at Cleveland State University, advocated for plant literacy as a strategy for fighting inequalities in access to industrialized food. As the director of the Goosefoot Acres Center for Resourceful Living in Ohio, he had a significant role in spurring concern of pesticide use dangers and environmental awareness.

The Dandelion Celebration

In The Dandelion Celebration Gail reports how dandelions, under the name “ciccoria”, used to be a popular food not only for Italian-American communities, but also for many individuals with diverse national and cultural backgrounds, including the English, Germans, Koreans, Lebanese, Greeks, and Armenians (12). Dandelion, which is defined as “an invited species” in the Introduced Species Project (ISP) sponsored by Columbia University, was broadly understood as a crop and used in an incredible number of dishes. As a matter of fact, the ISP stresses how evidence shows that throughout history “dandelions have been purposely carried across oceans and continents by human beings”, and “European settlers brought these plants intentionally to America”.

Peter Gail remarks how Italian-American communities who considered the plant an asset of their diet used the word “ciccoria” to refer to dandelions. Like for many other plants, the history of the name “dandelion” is debated and unclear. However, it is interesting to observe that such a linguistic variance, with different names assigned to the plant depending on its attributed value, characterizes much of the history of the social life of dandelions. The Italian “cicoria” indicates in fact an edible bitter plant (“ciccoria” pronounced and spelled with a double “cc” seems to indicate a dialectal variant), while any dictionary will indicate that the proper translation for dandelion is dente di leone (literally “lion’s tooth”) or tarassaco (from taraxacum officinale).

Most discussions of the English word dandelion focus on its likely derivation from the French “dent-de-leon”. In The names of plants, David Gledhill traces the origin of the term taraxacum to “the Arabic names tarakhshagog, for ‘disturber’, or to talkhchakok, indicating” -like the term cic(c)oria – “a bitter herb” (371). Although the history of plant names presents innumerable challenges, including the issue of identification, it is interesting to observe that two main semantic areas are activated by etymological research around dandelions. The reference to plant morphology, its behavior, or its flavor suggests in fact the existence of two distinct epistemological approaches to dandelion, both at the intersection between plant and human experience. In one approach, with etymologies highlighting the pointy leaf shape or the ubiquitous presence of the plant, the origin of the name is traced back to the phenomenological characteristics of dandelions as they emerge through sight and observation. The other approach, on the contrary, focuses on the plant flavor and properties when ingested by humans, thus proceeding through taste and a form of “metabolic understanding”. We could perhaps consider the two approaches as the result of either a botanic or a medical understanding of plants.

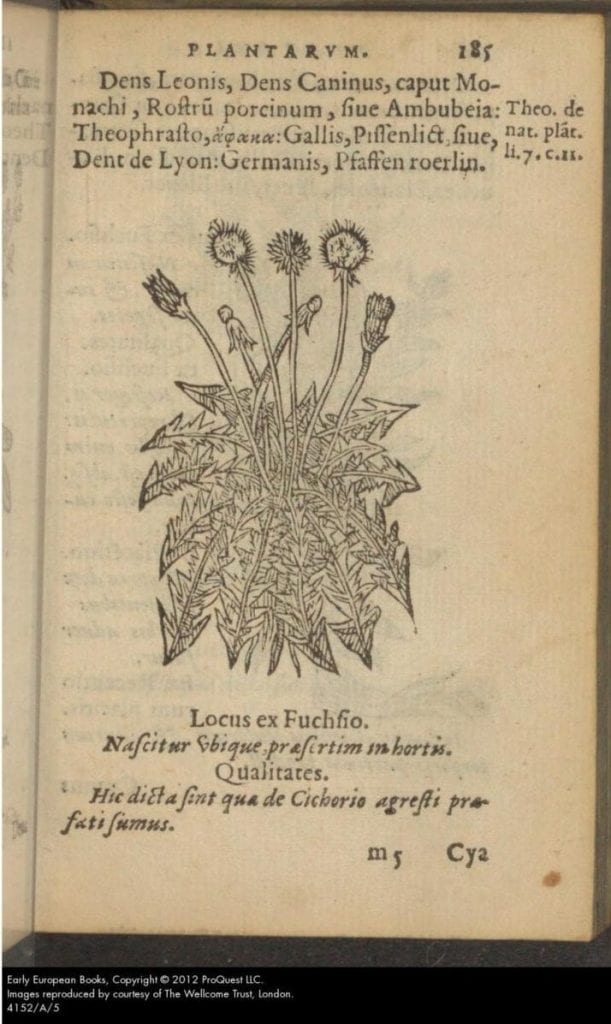

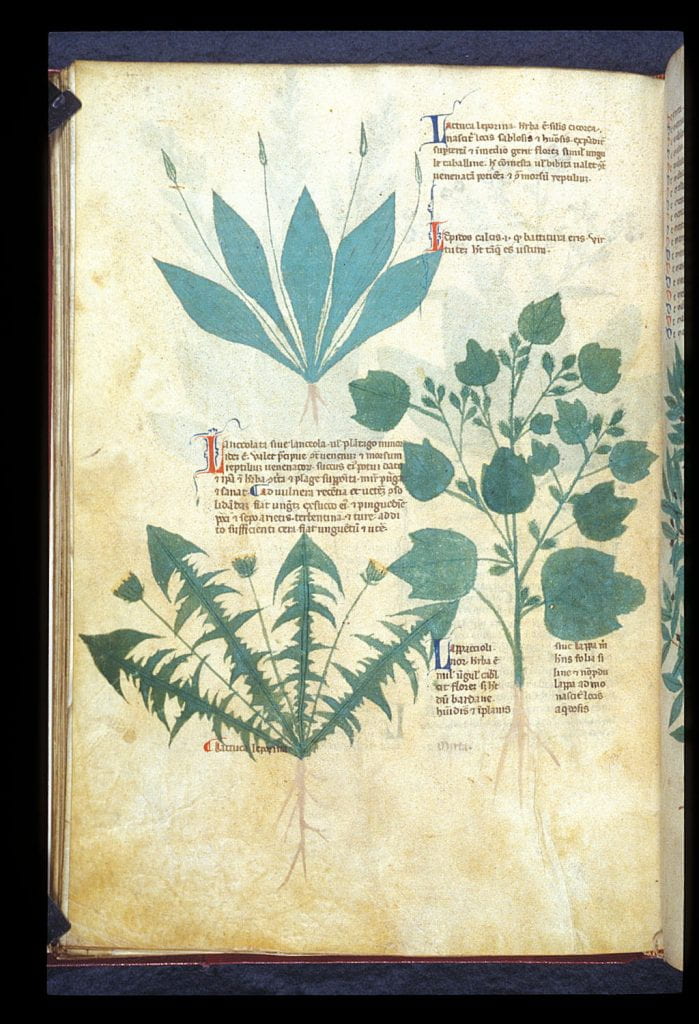

As a matter of fact, earlier medieval texts seem to prefer the definition “lactuca” under images of dandelions, which might be explained by the fact that dandelions, like other plants in the family, produce a milky substance when cut. The term “dens leonis” (lion’s tooth) which highlights the morphology of the plant seems to be a late term. It appears in fact in the most popular 16th-century herbals written in Latin by the Italian Pietro Andrea Mattioli and the German Leonhart Fuchs, and rendered in English by William Turner. I could not find the Latin “dens leonis” in any of the medieval herbals I consulted, nor in canonical Latin texts such as Pliny’s Naturalis Historia. In Dioscorides’ On Medical Material and Theophrastus’ Enquiry into Plants there are references to plants which are usually identified as dandelions, but there seem to be no references to the lion imaginary regarding the appearance of the plant. According to a 1526 German edition of the Hortus sanitatis, the term “dens leonis” was coined by a German surgeon who was very fond of the plant.

The issue of naming came to constitute the coordinates orienting my journey through shifting understandings of dandelions. As a matter of fact, in my own experience, the more Italian name of “dente di leone” slowly erased the familiar terms “cicoria” and “piscialetto” (literally “pee-the-bed!”) that I learned while foraging the herb as a vegetable with my grandmother in the fields around Badia Pozzeveri (a place which recently gained fame for its Field School in Medieval Archaeology and Bioarchaeology). It wasn’t until I moved to Florence and started going to an urban school that I learned that the plant, with the name of “dente di leone”, was a weed. The awareness of the distinction between weed and food came for me with a new name, which erased the more familiar term “cicoria”.

Weeds occupy ambiguous space in thinking about and with plants. Scholars in plant-ecology and plant- philosophy encourage us to reflect on such an inherent ambiguity with the aim to engage in a way of thinking that is “edifying, conversational, and interpretative” rather than “demonstrative” (Gianni Vattimo and Santiago Zabala, xii-xiii).” The assignment of plants to the category of weed, ornament, or food in fact allows us to expose the different patterns of human ecological practices – growing crops, making roads, maintaining city surfaces, designing backyards – while reflecting on their underlying cultural assumptions. Among the multifaceted directionality of plant-thinking, the distinction between weeds and non-weeds constitutes an interesting site for exploring the implications and contradictions of taxonomic approaches to the world. Being defined in relation to human interests and spaces, such a distinction is not only based on a hierarchical organization of living beings, but also on shifting socio-economic practices that define what plants are allowed to exist or not and where. The fact that certain plants have been historically understood as either food, ornaments, or weeds speaks to the many socio-economic variables at play in the categorization of plants. Names often preserve traces of the social life of plants. With this in mind, along with a lot of other personal reasons, I will continue to pay attention to the story of dandelions, and their ambiguous existence on the border between weeds and food.

Author Bio

Featured Image: Dandelion plant in the city center of Florence, Italy (detail). Photo by author.