By Daniel Bottino

Symonds Baker, a thirty-two year old resident of Little River, near the mouth of the Androscoggin River in mid-coast Maine, testified in 1796 that during May of the previous year “I was walking along By a Place (at the Head of the Ten Miles Falls so called on Amorouscoggin River) Where there was an appearance of an old cellar and Chimney and that I found the Blade of a small sword.” In another deposition taken two days later, Abraham Witney, also of Little River, confirmed Baker’s find of a sword and added that “about twenty four or five years ago there was an old iron hoe with an iron handle ploughed or dug up about fifty rods from Purchases Cellar which appeared to be a garden hoe.” The “old cellar” mentioned by these two men was the presumed house site of Thomas Purchase, one of the earliest English colonists of Maine, who had come to the area around the mouth of the Androscoggin sometime during the 1620s.

The depositions of Baker and Witney, along with more than 50 others taken around the same time, were recorded with the object of determining the location of Purchase’s long abandoned dwelling, a subject of considerable controversy and legal import. A thoughtful historical analysis of these depositions, currently held as part of the Pejepscot Papers at the Maine Historical Society, reveals much more than local disagreements between neighbors in late eighteenth-century Maine. For through these documents I believe we are afforded a rare glimpse into the processes of colonialist memory creation and perpetuation. In the multitude of voices that speak from this collection of depositions, a dominant theme emerges: the belief that English colonization could leave an indelible trace upon the landscape, thereby creating a memory that could endure through the generations as a justification for continued possession and colonization of the land.

The legal case that occasioned the inquiry into Thomas Purchase’s house site was a dispute between the state government of Massachusetts (of which Maine was a part until 1820) and the Pejepscot Company, a land company that had sponsored eighteenth-century English colonization in the region just north of modern-day Portland, Maine. As the Pejepscot Company’s claims to legal title could be traced back to the original land grant of Charles I of England to Thomas Purchase, it seems that the court put considerable effort into ascertaining where Purchase had lived in the hope of establishing the correct bounds of the Pejepescot Company’s land claims. Significantly, there seems to have been no extant copies of the land patent held by Purchase by the time of the court case. As a 1683 deposition in the Pejepscot Papers reveals, Purchase’s personal copy of his patent from the king was lost when his house burned down sometime before 1653. The loss of this document must have been of great concern to Purchase, for another deposition from 1693 reveals that, aged nearly 100 years, he sailed to England “as he said purposely to look after & secure his said Pattent.” It is not known whether he found the document, and I do not believe it to exist today. Thus, after Purchase’s death, in the absence of this written document, it was the disputed and contradictory oral memory of Purchase’s inhabitation that assumed the primary burden of validating his legal claim to colonization in Maine.

This was a rather dubious enterprise, as the testimony of the deponents, a group consisting for the most part of middle-aged and elderly men, demonstrates that opinion was split between two possible sites of Purchase’s house, with no conclusive proof for either site. But what all these men did agree on was a shared conviction that “one Purchase,” as he was often termed in their testimony, had at some distant time early in the seventeenth century begun the English colonization of the land, a colonization maintained and continued by the region’s white inhabitants in their own time.

It is in this context that we should understand Baker and Whitney’s discovery of a sword and a hoe at the site where they believed Purchase had lived, for these were symbols of successful English colonization par excellence. In the minds of late-eighteenth Mainers who saw themselves as heirs to Purchase’s pioneering colonization, he had asserted his land claim through his military prowess (the sword) and his willingness to farm and thus “improve” the land (the hoe.) Whether these rusty artifacts did really belong to Purchase, or indeed existed at all, the assertion of their existence by Baker and Witney represents the attempted creation of a memory of English colonization tied to the landscape in which they lived. Indeed, it is the apparently evident Englishness of Purchase’s supposed house site that appears over and over in the depositions. For example, John Dunlop recounted that “I have seen at the head of s[ai]d falls on the easterly side of the river, a place which appeared to be the settlement of some English planter where a large cellar was dug, and remained still to be seen, which I never saw in any Indian settlement, which appears to be very ancient.”

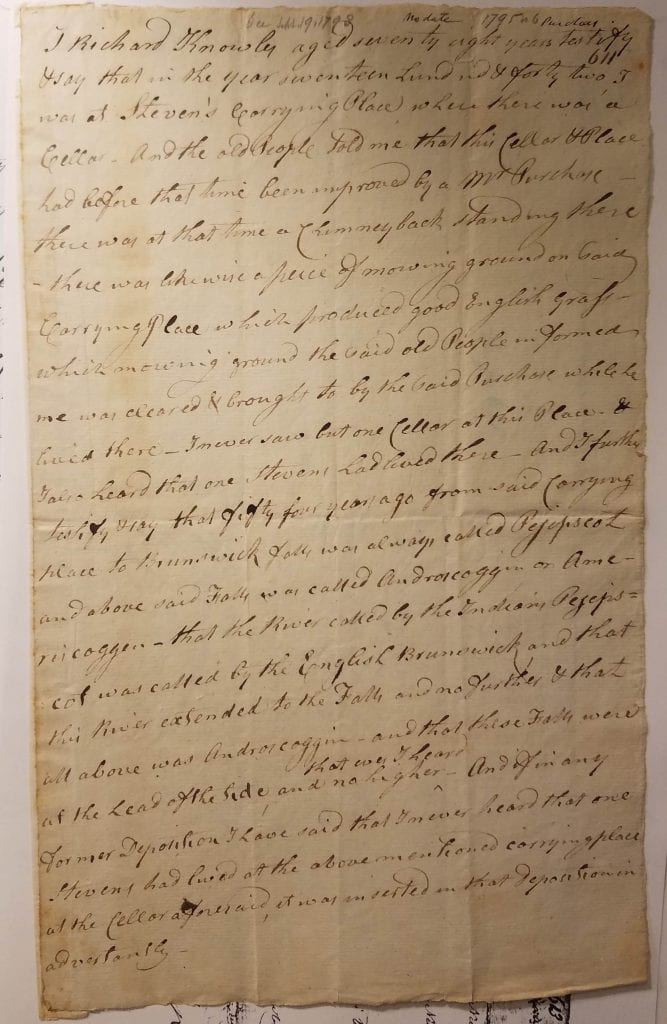

Dunlop’s account stresses what he saw as the non-Indian appearance of the cellar hole—his mention of “some English planter” also emphasizes the fundamental association of English colonization with agriculture. This “improvement” of the land, as it was often termed in seventeenth and eighteenth-century documents, appears in many of the depositions. Thus Richard Knowls told the court that as early as 1742 he had seen “a Celler on said Place and the Old People told me that this Celler and Place had before that time been improved by a Mr Purchas…there was likewise a peace of Mowing ground on said Caring place which produced good English Grass which Mowing ground the said Old People informed me was cleared & brought to by the said Purchas while he lived there.” In describing the site’s “good English Grass,” Knowls marks the abandoned cellar hole as a mnemonically powerful site, whose grass perpetuates the memory of Purchase’s colonization across more than a century. In doing so, Knowls and the “Old People” who passed on their memories of Purchase to him were participating in the creation of a history of successful English colonization in Maine, a fabricated history that also, critically, aimed to erase the memory of Native inhabitation.

However, this process of colonialist memory creation was neither stable nor unchallenged, and the depositions reveal this quite clearly. In addition to the most prominent flaw in the construction of the memory of Thomas Purchase, namely the disagreement over the location of his house, some deponents even raised doubts over the supposed Englishness of one of the possible house sites (the other site was undoubtably English, and dispute centered around its age). Most notable in this respect are the words of Timothy Tebbetts, who when asked how he thought the supposed cellar hole had been made, answered “Either by Indians or English it look’d like the work of some human Creature.” Although other deponents, such as John Dunlop, had testified that this same cellar hole was undoubtably English in origin, in Tebbetts’ testimony we see an element of doubt enter into the picture. At least for Tebbetts, the mnemonic power of the landscape was insufficient to distinguish English settlement from Indian settlement—if the cellar hole had indeed once been Purchase’s house, in Tebbetts’ estimation the ruins were no longer able to transmit the memory of Purchase’s ancient inhabitation.

This deposition confirms a fundamental truth about the colonial memory I have explored here: it was rightly perceived as extremely fragile in all of its forms, whether textual, oral, or as physical marks upon the landscape. This is why so many times in the depositions, as we have seen in the case of Knowls, “old people,” often fathers or relatives, are described as revealing widely held historical memories to young men. This was a mainly oral tradition whose stories were only rarely written down. And it is important to remember that written texts were also fragile, especially in the context of life in rural Maine, as we have seen with the example of the loss of Purchase’s original land patent. As the marks Purchase made upon the landscape were overtaken by nature, the fragile oral memory of his inhabitation slowly faded out. But despite the tenuousness of the memory of Purchase by the 1790s, it still endured to be recorded in the written depositions that have survived to the present day.

Above all else, these depositions reveal a deep-seated desire among many male white inhabitants of the region to assert the success of earlier English colonization in Maine, of which they were the symbolic heirs. For these men, ancient claims of English ownership of the land assumed pre-eminent importance, such that they even dug around in old cellar holes in search of rusted artifacts as proofs. But it is important to remember that this view was not shared by everyone. And so I will end with the deposition of Martha Merrill, the only deposition in the archive of the Pejepscot Papers made by a woman alone. Speaking to an agent of the Pejepscot Company in reference to the company’s land claims, Merrill declared that “I would not give him two Coppers for it all.”

Daniel Bottino is a PhD student at Rutgers University, where he studies early modern European and early American history. His dissertation research focuses on the interaction of cultural memory with the law and the physical landscape in early modern England, Ireland and colonial Maine, with an emphasis on the role of cultural memory in the process of English colonization.

Featured Image: Cellar Hole in Vaughan Woods State Park, South Berwick, Maine. Photo courtesy of author.