This is the first installment of a two-part interview with Hannes Bajohr, Florian Fuchs, and Joe Paul Kroll about their new volume, History, Metaphors, Fables: A Hans Blumenberg Reader (2020). Read the second part here.

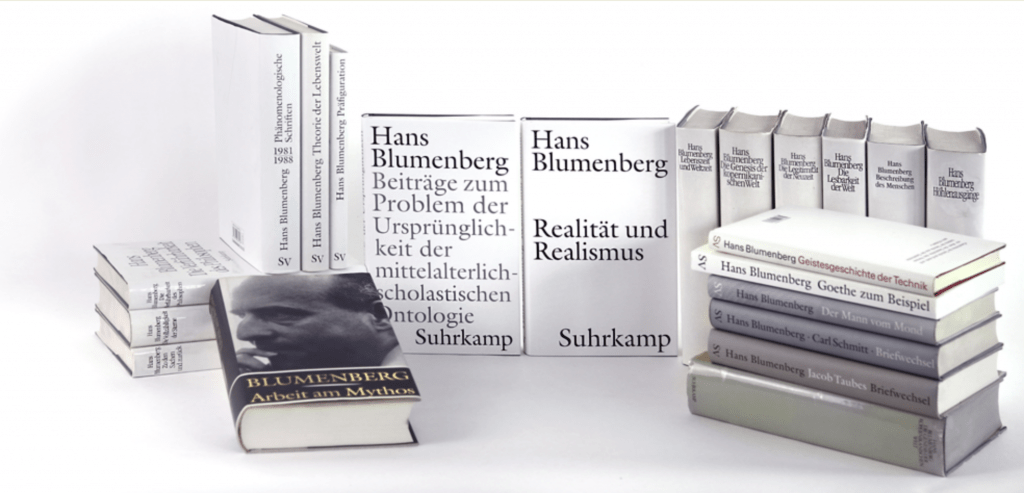

The German philosopher and intellectual historian Hans Blumenberg (1920–1996) has fallen into the spotlight as of late. Known for influential studies including The Legitimacy of the Modern Age (1966) and The Genesis of the Copernican World (1975), over a dozen additional volumes of his more experimental writings and unfinished manuscripts have appeared posthumously. In recent years, a number of major conferences and a 2018 documentary have been dedicated to his work, while newly-published editions (his dissertation on the problem of primordiality in medieval ontology) and correspondence (with Carl Schmitt and Jacob Taubes) have appeared in German, with some English translations following. The new essay collection, History, Metaphors, Fables: A Hans Blumenberg Reader was published in June 2020 by the Signale imprint for German thought at Cornell University Press. The volume is edited and translated by Hannes Bajohr, Florian Fuchs, and Joe Paul Kroll. Bajohr has also contributed to the Blog’s continuing coverage of Blumenberg scholarship, one highlight of which was a forum from last year on Blumenberg and political myth. Contributing editors Andrew Hines and Jonathon Catlin, who organized that forum, interviewed the editors about this new edition of Blumenberg’s writings.

Jonathon Catlin & Andrew Hines: This year marks the one-hundredth anniversary of Blumenberg’s birth, which has led to an outpouring of interest in him, prompted by several recent books: Rüdiger Zill’s Der absolute Leser – Hans Blumenberg. Eine intellektuelle Biographie (2020), Jürgen Goldstein’s Hans Blumenberg: Ein philosophisches Portrait (2020), and Kurt Flasch’s Hans Blumenberg. Philosoph in Deutschland. Die Jahre 1945 bis 1966 (2017). I was struck by a review that said contemporary readers steeped in critical theory might be surprised by how traditional Blumenberg’s university environs were, centered as they were on classicism, philology, idealism, and phenomenology, and “not yet enlightened by linguistic analysis.” There were also legacies of the Nazi regime, which had persecuted Blumenberg as someone partly Jewish, but which long remained a taboo subject. We learn in these recent works that he once remarked of continuing to work with former Nazi academics, “I didn’t want to be what I didn’t have to be: the Last Judgment.” Shortly before his death, he wrote, “This country has remained scary to me, although I have rarely left it….In this country nothing that made Hitler possible has vanished into thin air…” Were there any revelations here for you?

Joe Paul Kroll: It’s worth noting how attached to the traditions of the German university Blumenberg was, even if the student revolt, beginning in the 1960s, came to identify those traditions with darker continuities that had not been adequately addressed. Blumenberg tended to see the ugly German rearing his head in the behaviour of the radicals rather than in institutional or personal continuities, and was horrified by left-wing militancy and terrorism in the 1970s, which he found to be wholly destructive and redolent not just of the Nazis, but even of the early modern Landsknechte. As for “former Nazi academics,” he was (often) willing to give them the benefit of the doubt, both personally and, as it were, institutionally. I can only assume that he felt the university system to be a haven and that its politicization was the problem. This does not mean that he found the continuing influence of certain individuals or interactions with them to be unproblematic.

Hannes Bajohr: The wish not to be the world court or the Last Judgment (Weltgericht) also stems from the fact that Blumenberg was only able to survive the Third Reich as unscathed as he did because party members helped him: First, there was Heinrich Dräger, the owner of the Dräger factory where Blumenberg was able to work and to earn a living between 1943 and 1945, and who continually claimed to the authorities that he was indispensable. Second, after Blumenberg was able to get out of the work camp to which he was deported in 1945, again with the help of Dräger, he found refuge with his former driving instructor, also a party member. However, this does not mean that Blumenberg was all-forgiving: He advocated for the ouster of a professor who—having been a strong proponent of eugenics under the Nazis—kept working at the University of Kiel after 1945, but to no avail. That he later reacted with such vitriol to, for instance, the accusations against Heidegger for his Nazi sympathies is certainly due to his antipathy to the New Left of the seventies, as Joe has mentioned. One must not forget that there is also development in Blumenberg’s politics: He started out as a Catholic thinker in the 1940s who turned into a liberal apologist of modernity in the 1960s, and became more conservative again in the later 1970s and 1980s.

Florian Fuchs: A biographical revelation that had a clarifying effect on understanding Blumenberg’s work for me was how consistently and almost systematically he withdrew from almost any kind of collaborative and social interaction, not just in the later years, which had been well known, but almost all along and with little differentiation as to with whom. In the past, scholars have presented these withdrawals as strategic techniques of Blumenberg within the politics of academic projects, that is, as directed against certain groups of colleagues or single interlocutors. But the episodes that Zill lays out one after the other show that Blumenberg’s withdrawal is systematic and rather follows its own inherent private tactics, without ever being meant as part of any actual communication to his contacts. The rigorousness of this behavior then ultimately complicates, or even prohibits the biographicization of his books or projects, instead of warranting cross-reading to detect his alleged positioning of essays or books for or against certain people or institutions.

JC & AH: It is also the seventieth anniversary of the founding of the renowned German publisher Suhrkamp’s series Theorie, which for a time Blumenberg edited with Jürgen Habermas, Dieter Henrich, and Jacob Taubes. We gather that Blumenberg stepped down from this role over conflicts with the publisher’s editor, Siegfried Unseld. Granting Florian’s point about Blumenberg’s independence, what were some of the animating concerns of the intellectual milieu in which Blumenberg wrote many of the essays in this Reader?

JPK: I find it hard to answer that question beyond a general reference to the discussion group Poetik und Hermeneutik, in which Blumenberg was involved only for the first four sessions, and whose animating concern was to find some kind of common ground within the realm of Geisteswissenschaften (humanities) at a time when methodologies seemed to be diverging to the point of mutual incomprehension. One striking thing about the recent biography of Blumenberg by Zill is that it’s very much not a “life and times” kind of book and largely omits intellectual debates that Blumenberg did engage in with his contemporaries, situating him rather in the context of academic politics. This would seem to dovetail with Blumenberg’s self-mythologization as someone writing largely for himself and for posterity, which may not be the whole truth, but certainly derives some plausibility from the sheer volume of writing that was not published in his lifetime but which was clearly conceived as part of the greater Werk. One more point would be that Blumenberg was not part of the so-called “Suhrkamp culture,” of which Habermas is perhaps the emblematic figure. Indeed, Habermas seems to be the most important contemporary whose work Blumenberg seems largely to have ignored.

JC & AH: There is also Blumenberg’s relationship to Husserl and Heidegger, whom he engages in his early essays in the Reader on phenomenological approaches to technology. One trouble is that Blumenberg’s writing style often leaves one guessing just who he is implying in certain arguments. There is a school of thought, including Anselm Haverkamp and Dirk Mende, that has argued that Blumenberg’s writings in the 1960s, particularly Paradigms and some surrounding correspondence, is an implicit engagement with Heidegger, for example on language as a tool, and an attempt to offer “metaphorology” as an alternative to Heidegger’s fundamental ontology. In your biographical introduction, however, you suggest a clean break with Heidegger. How does this Reader, as you have created it, allow us to engage with this coded style of writing in which, some would argue, references to particular authors aren’t always made explicit?

HB: Blumenberg came to phenomenology through Catholicism, but it was phenomenology that remained at the basis of his thought. I think the relationship to Heidegger has to be seen in this light. Blumenberg’s teacher Ludwig Landgrebe was a Husserlian who read Heidegger not so much as a rebel of phenomenology but as an innovator of its main program who pointed out some flaws in Husserl’s initial attempt. Already in the 1950s, Blumenberg turned against Heidegger as obscurantist and misguided, and later he would write that the question of the meaning of being is one of the less interesting ones in the history of philosophy. But he held on to what Landgrebe saw as Husserl’s useful reaction to Heidegger’s critique of the notion of epoché, the bracketing of judgments on the existence of what is given to consciousness. Famously, the concept of Being-in-the-world reacts to the all-too distanced, Cartesian attitude that the epoché presupposes. Landgrebe, and with him Blumenberg, points out that Husserl already had a notion of engaged world relation in the flipside of the epoché, which he called the natural attitude and which later he fashioned into the concept of the life-world, the preconceptual sphere of world engagement. One can disagree as to whether the life-world really is a useful equivalent to Being-in-the-world, but for Blumenberg Heidegger had not really gone beyond Husserl in any meaningful way. The interpretation that Heidegger is the main target, at least in my view, misses the mark. Husserl is a much more direct influence, and Heidegger, channeled through this reading as a corrective to Husserl, a secondary character in comparison.

To your second point, it has frequently been remarked that Blumenberg did not like to present his ideas in grand intellectual lineages, and even went to great lengths to obliterate references to his contemporaries. This is not always the case, as the notable exception is the second edition of Legitimacy of the Modern Age, where he answers his critics (this edition is the basis of the English translation, which is why it is so difficult to follow its palimpsestic structure). But on the whole, he makes a point of not engaging with other thinkers by name. Still, I think it may be putting it a little too starkly when saying he “ignored” Habermas, for instance. Rather, he addresses him circuitously, by not naming him directly—for example in “An Anthropological Approach to the Contemporary Significance of Rhetoric,” where Blumenberg develops an alternative notion of “consensus” (but uses the italicized Latin form, not the German Konsens Habermas employs). And as Brad Tabas has pointed out, Blumenberg often uses historical figures as stand-ins for contemporary ones: Hobbes for Arnold Gehlen and Carl Schmitt, Hegel for the Frankfurt School—even Napoleon for Hitler in Work on Myth. This elusiveness is certainly another self-stylization. He strove, as Jürgen Goldstein called it, for “classicism” in his work, and classicism is not in the business of academic bickering or penning op-eds on current events.

FF: Hannes put it nicely: Blumenberg addresses others “circuitously,” and I would add, he does so almost by default and in the double sense of addressing them both indirectly and laboriously, that is, often covering his own tracks of having done so. From any reader of Blumenberg, that demands heightened caution not to be misled by seemingly clear references, and perhaps our Reader helps a bit here because we marked and referenced some quotations not made explicit in the original German. This practice, in consequence, makes it always more difficult to place Blumenberg within certain lineages of reception than meets the eye. He might refer to one interlocutor just to avoid mentioning another, or worse, in the negative, avoid mentioning Hegel to avoid having to mention Adorno; but in each case, the motivations become comprehensible only in the context of the ongoing larger argument.

That certainly goes for Heidegger, too, but it has always been my sense that Heidegger is rather the model case for this indirect mode of reception and critique, with the main reason being what Hannes just outlined: Phenomenology was always more significant for Blumenberg than Existenzialontologie or Seinsgeschichte. Yet in the intellectual climate right after the war, in which Heidegger and his school could not be avoided, Blumenberg, while still being very much concerned with keeping philosophy intact as a social project, chose to address Heidegger largely by determinate avoidance. For me, his original (and fairly straightforward) gesture here is his critique of a “monologic” jargon in contemporary philosophy in the “Linguistic Reality of Philosophy” (1946/47) essay. Against the overburdening of philosophical language with quotidian equivocations—a clear reference to Heidegger, in my understanding—he demands, despite all valid complications with metaphysics, a return of the Husserlian care for philosophical language in order to achieve a philosophical dialogicity. That is not at all to say that Blumenberg’s critique of philosophical language was designed as an anti-project to Heidegger’s highly idiosyncratic turn away from phenomenology, but it was certainly developed as an alternate program for thinking through the tensions between life-world and self that Husserlian phenomenology had begun to identify.

JC & AH: Blumenberg once said the task of philosophy was “the dismantling of the obvious” [Abbau von Selbstverständlichkeiten]. He likewise wrote in the 1971 essay “An Anthropological Approach to the Contemporary Significance of Rhetoric”: “I see no other scientific course for an anthropology except, in an analogous manner, to destroy what is supposedly ‘natural’ and convict it of its ‘artificiality’ in the functional system of the elementary human achievement called ‘life’.” (188) The difficulty of Blumenberg’s work can be partly explained by the fact that he hardly belonged to any political or ideological camp, but rather developed a variety of such critical approaches. In a recent reminiscence on Blumenberg, his former student Uwe Wolff thus writes that there was no “Blumenberg School” to speak of, and in a recent review of your Reader, Robert Pippin similarly calls Blumenberg “unclassifiable.” Nevertheless, we wonder whether you see some enduring commitments and concepts across his oeuvre: perhaps the notion of the “absolutism of reality,” or, as he puts it elsewhere, the modern “awareness of reality’s contingency” that catalyzes the justification of the life-world (395).

JPK: One might also translate Abbau—as Derrida did when he encountered the term in Heidegger—as deconstruction. To do so would, however, be somewhat tendentious. There is no triumphant calling out of the naked emperor in Blumenberg, and no suggestion that the layers of meaning concepts accrue over time are in some way “inauthentic.” The Entselbstverständlichung to which he refers is something almost incidental to the development of thought and language and in that sense connects with the Lebenswelt, that notional realm of the self-evident which seems always to be receding from view. If one were to classify Blumenberg as anything, it might be as an observer of such processes rather than their agent.

As for the “absolutism of reality,” Odo Marquard—whom I like to think of as the Diogenes Laertius among Blumenberg’s biographers—placed that term at the center of his interpretation and reports that Blumenberg, when asked if he agreed, replied: “I am dissatisfied only with the fact that it is possible so quickly to notice that everything more or less comes down to that idea.” (Hannes recently translated the text in question.) Make of that what you will. I don’t think it’s an unhelpful interpretation as such, though it may mislead unwary readers into thinking that Blumenberg was some kind of therapeutic philosopher, and it would certainly be counterproductive to try and force all of Blumenberg’s concerns into such a narrow framework.

HB: If I can take up a thread from the previous question, I would say one enduring commitment is indeed the notion of the life-world. First, in what Blumenberg referred to as “historical phenomenology,” he describes historical life-worlds (or more precisely, the historical horizons of the life-world). He calls “concepts of reality” the conditioning structure of what, in an epoch, can appear as real; the contingency of reality as a fundamental structure of human world-relation historicizes the real. I would say that this also feeds into his metaphorology—one way of reading it is as the attempt to infer, through language, these reality concepts. So, for instance, the metaphor of truth as light must understand reality as immediately evident, as opposed to truth as something to be won in struggle, which conceives of reality as evasive. One can read this as an echo of the Heideggerian history of being, but I believe that if anything the reference to Heidegger is purely negative; Blumenberg was, after all, deeply hostile to ontology, and he repeatedly separated his notion of reality from that of being.

The life-world also plays a role in his “phenomenological anthropology,” which tries to make up for Husserl’s “forgetfulness of the body” (not unlike Merleau-Ponty did). It explains what in Husserl must remain unexplained—the beginning of consciousness—by adding an evolutionary perspective: human consciousness emerges from the becoming-human of the first hominids, and this in turn means interpreting the life-world as the threshold of humanization—it is always already behind us. This plays a role in Description of the Human but also in Work on Myth. Here, the Husserlian commitment is equally evident, and it would be hard to argue that this anthropology reacts in any way to Heidegger; Husserl, not Heidegger, remains the central point of reference.

Nevertheless, it is worth keeping in mind that Blumenberg’s work is made up of different phases, as the Reader shows. The concern with phenomenological anthropology—correcting Husserl by employing the German tradition of philosophical anthropology connected to names like Max Scheler, Helmuth Plessner, and Arnold Gehlen—and to which Marquard’s quip refers, is a rather late development, beginning with “An Anthropological Approach.” But you find little about anthropology in the work of the 1960s, especially if you look at the texts dealing with secularization, reality, and history. The “absolutism of reality” may certainly be a useful, if reductive, title for the work of the 1970s, but the 1960s are much more characterized by an interest in modeling the self-understanding of historical epochs through differing “concepts of reality.” The 1980s, on the other hand, show some stark shifts—in style toward more literary forms, and in concern staying with anthropology but not so much describing it theoretically, but rather investigating its effects through analyzing genres like fables and anecdotes.

FF: I agree with Joe and Hannes, and would like to add the case of metaphorology, perhaps counterintuitively, as a Blumenbergian commitment than as a concept. In fact, metaphorology the concept and the method more or less failed, especially with respect to its original installment vis-à-vis, or better, side by side with the history of concepts. I know of no other “metaphorologist,” and, strictly speaking, even Blumenberg may not be one, after all. Metaphorology the commitment succeeded, however, and was successful, albeit under different labels: Blumenberg coins the term very early in the essay on the light metaphor (possibly as an indirect result of his earlier notion of a “metakinetics” of historicity from his 1950 habilitation, if one follows Anselm Haverkamp), and attempts to install it as a method with the “Paradigms,” but then only has it return a decade later in the context of his anthropology and narrative philosophy from the “Observations” onwards. During this long arc, it develops from the identification of an overlooked problem in the history of philosophy, to a programmatic initiation of a large research project, to an implicit and later explicit but always idiosyncratic method of his own reading and writing, up to its later modulations into essays about “nonconceptuality” with regard to anthropology and “nonunderstanding” with regard to fables. From this perspective, there’s a consistent and traceable commitment to metaphorology, perhaps conceived as attention to the orienting function of language for the thinking of realities.

Hannes Bajohr is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Media Studies Department at the University of Basel. He received his doctorate with a dissertation on Hans Blumenberg’s theory of language from Columbia University, New York, in 2017.

Florian Fuchs is a Postdoc and Associate Researcher in the German Department at Princeton University. In 2017, he received his Ph.D. from Yale University with a dissertation on the rise of short narrative forms and civic storytelling from the 18th to the 20th century.

Joe Paul Kroll received his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 2010 with a dissertation on the secularization debate between Hans Blumenberg, Karl Löwith, and Carl Schmitt. Following a stint in the publishing business, he now works as a freelance translator and occasional writer.

Jonathon Catlin is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History and the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM) at Princeton University. His dissertation is a conceptual history of “catastrophe” in modern European thought. He tweets @planetdenken.

Andrew Hines is Lecturer in World Philosophies at SOAS University of London and the Thyssen Research Fellow at the Centre for Anglo-German Cultural Relations at Queen Mary University of London. His first book is Metaphor in European Philosophy after Nietzsche: An Intellectual History (2020).

Featured Image: “Bekanntester Unbekannter” – Hans Blumenberg (Peter Zollna / Suhrkamp Verlag)

1 Pingback