By Michael R. Sheehy

Over the past thirty years, driven chiefly by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama (b. 1935), the dialogue between Buddhism and normative Western science has significantly been shaped by Tibetan Buddhism—and Tibetan Buddhism, in turn, is being shaped by modern science. In 2005, the Dalai Lama published The Universe in a Single Atom, a book that has been dubbed his “scientific autobiography.” Here, the Dalai Lama concedes classical Buddhist cosmology to modern scientific cosmology, stating that the classical cosmology detailed in Buddhist Abhidharma literature needs to be updated:

There is a dictum in Buddhist philosophy that to uphold a tenet that contradicts reason is to undermine one’s credibility; to contradict empirical evidence is a still greater fallacy. So it is hard to take the Abhidharma cosmology literally. Indeed, even without recourse to modern science, there is a sufficient range of contradictory models for cosmology within Buddhist thought for one to question the literal truth of any particular version. My own view is that Buddhism must abandon many aspects of the Abhidharma cosmology.

Dalai Lama 2005, 80

For the Dalai Lama to abandon an ancient Indic cosmology that Tibetans inherited over a millennium ago probably seems logical to most modernists, even politically savvy for a dialogue with Western scientists. However, closer inspection reveals that European ideas about the cosmos are not new to Tibetan scholars and were in fact known in Tibet since the early modern period.

As indicated in the criticism voiced by McMahan and Braun and others, the ongoing public dialogue between Buddhism and science operates largely without express consideration of its broader social, metaphysical, and cultural contexts, including the history of scientific encounters between the two sides. Important tensions exist in the study of how context informs the dialogue between Buddhism and science and its broader cultural impact as well as the reception of scientific knowledge by Tibetan Buddhists. Here, I reflect on milestones in the history of the encounter between European and Tibetan theories of the cosmos in Tibet prior to the 20th century—not only to challenge the still pervasive assumption that Tibetans were naïve about science up until the mid-20th century, but also more specifically to provide historical context for the topic of remaking cosmology in the public intellectual dialogue between Buddhism and science.

An often-cited watershed moment for the encounter between Tibetans with modern science is the June 1938 issue of the Tibetan language newspaper Tibet Mirror. In this issue, the Tibetan monk and modernist scholar Gendun Chöpel (1903-1951) published his famous essay “The World is Round or Spherical.” Written from outside Tibet, while he was on sojourn in South Asia, Chöpel scolds his Tibetan compatriots by claiming that they “hold stubbornly to the position” that the world is flat, a view held within classical Buddhist cosmology, even when presented with the evidence of modern science. Both Tibetans and Western scholars have lauded Chöpel’s essay as a radical introduction of a new theory of the cosmos that, for the first time, questioned Tibetan beliefs about Buddhist cosmology.

However, in stark contrast to a narrative that likens Chöpel’s round-world essay to a paradigm shift in Tibetan beliefs about the cosmos, Tibetans were in fact engaging European scientific models in general, and the idea of a spherical Earth in particular, at least two centuries earlier. While there are myriad cosmologies in Tibet—Kālacakra, Dzokchen, Bön, etc.—the source most frequently cited by Tibetans for Buddhist cosmology is the third chapter on the explanation of worlds (lokanirdeśa) in the Abhidharmakośa or Treasury of Abhidharma, the 4th/5th century magnum opus by the Indian Buddhist scholar Vasubhandu. In this work, the majestic mountain Meru is described as the axis mundi in the midst of an expansive ocean in the center of the cosmos. Mount Meru is surrounded by seven square golden mountains, each half the size of the preceding mountain. In the valleys between each mountain are ever-swirling lakes full of treasures and wish-fulfilling gems. In the ocean that engulfs this cosmos, symmetrically orbiting Mount Meru in each of the four cardinal directions are continental landmasses. In the east is the continent of Sublime Bodies (lus ‘phags gling), the south is that of the Jambu Tree (‘dzam bu gling), the west is the Bountiful Cattle (ba lang spyod), and the north is the continent of Ominous Sounds (sgra mi snyan). The southern continent is the sawtooth-shaped Jambu Tree or Jambudvīpa, named after the “rose-apple” jambu species of tree that grows there, which is the location of India. Lands that were known to those who lived in India including Tibet, Sri Lanka, China, and Persia were assumed to be in the world of Jambudvīpa—hence, it refers more generally to the known world. This vision of the cosmos encompasses both the science of astronomy as well as geography. Thus for Tibetan Buddhists, to know the cosmos is to know both the universe as well as the topographical landscape of this world.

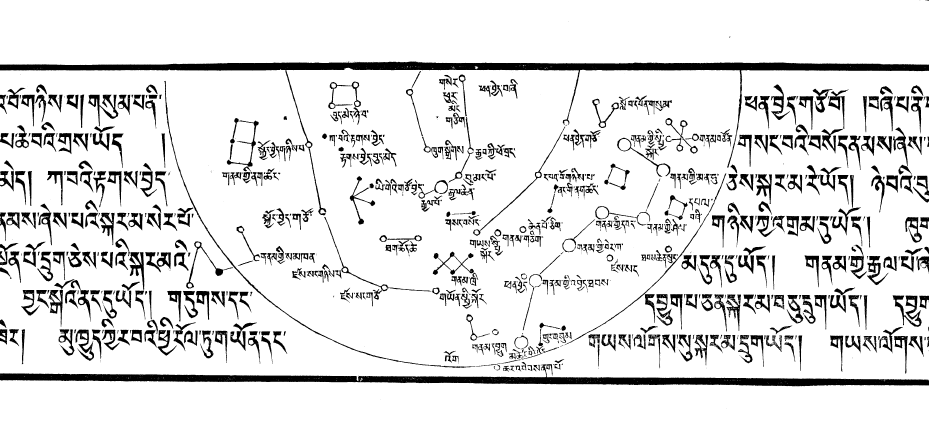

Tibetan astronomers shared a deep interest in the rigorous mathematics and observational methods of astral science (rtsis rig pa, *jyotiḥvidhā) with their Indian predecessors. In addition to the Indian Buddhist cosmological models that Tibetans inherited, over the past three centuries, they encountered and received astronomical and geographical knowledge about the observable universe, including knowledge about the spherical Earth and geocentric paradigm. Current scholarship detects first encounters between Tibetans and European science among Jesuit missionary astronomers at the imperial court in Beijing during the early 18th century. Under the direction of the Kangxi Emperor, Tibetan Buddhist lamas were employed to translate mathematical and calendrical texts from Chinese initially into Mongolian, and then in 1715, into the Tibetan language. At this precise moment, Tibetans began to receive, translate, and interpret newfound scientific knowledge about the order of the observable universe. The output of this translation project was The Great Compendium of Chinese Astronomy (Rgya rtsis chen mo), a compilation of thirty-two texts that comprise salient points of Jesuit telescopic astronomy.[1] Via the Qing imperial court, this translation laid the foundation for the adoption of Jesuit astral science in Tibet, spurring Tibetans to rethink their horological and calendrical practices, and reform their calendar in accordance with Jesuit calculations.

By the mid-18th century, Tibetans were engaging European mathematical theorems and were also incorporating new geographical data about the world—data that no doubt informed their cosmological thinking. Tibetans actively pursued this new knowledge and sought out methods to reform their systems of calculating space and time. Among Tibetan scholars engaging in this transformative process was the imperial court lama Akya Lobzang Tenpai Gyaltsen (1708-1768), whose collection of personal notes and commentaries range on topics in mathematics, astronomy, and trigonometry that he had studied in Beijing. His studies were strongly influenced by Jesuit scholarship and transmitted the Pythagorean geometric theorem as well as the vision that the Earth was spherical to intellectual circles in Tibet. Nearly two hundred years before Gendun Chöpel’s round world essay, Akya Lobzang Tenpai described the spherical (zlum po) Earth as follows:

This physical world is spherical. The sun, moon, planets, and majority of stars orbit above and below, and through their movements, via the influence of their transits, the moon overshadows the sun. When the moon, Earth, and sun are all directly aligned, the shadow of the Earth has the power to cover the moon, and this is said to be a lunar eclipse. [2]

Blo bzang Bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan 2000, 42a

Apart from The Great Compendium of Chinese Astronomy, Tibetan astronomers were already familiar with the idea of spherical planets from Indian Buddhist Kālacakra cosmology. Akya Lobzang’s writings indigenized the idea by providing a discussion by a prominent Tibetan author. His model of the Earth was not, however, Galilean heliocentrism but rather a geoheliocentric model in which the sun, moon, planets, and stars were assumed to orbit the Earth. This understanding derived from the Tychonic system, a model proposed by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) and the official system in use at the Qing court. Astronomic theories by both Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) were predominant in China during this period.

By the late 18th century, European scientific ideas had begun to circulate within Tibetan scholarship on astronomy, topography, and geography. Written in 1777, the General Description of the World (‘Dzam gling spyi bshad) by the scholar Sumpa Khenpo Yeshé Peljor (1704-1788) informed Tibetan orientations and representations about terrestrial space. Sumpa Khenpo’s work surveyed the world known to Tibetans at the time, including the familiar terrain of India, Nepal, Mongolia, and China as well as the outskirts of East Asia including Manchuria, Korea, and as far east as Japan. However, he ventured further to take his Tibetan readers on a voyage to Russia, where he described a magnetic iron citadel, bell sounds indicated change of time, bald men wore wigs, and inhabitants consumed sea monsters; to Sweden, where there was cutlery made of gold and crystal; to the Arctic Ocean, where he described white (polar) bears and seals, which that he called a “lizard the size of a dog”; and to the Ottoman Empire, where Turks dressed fashionably in hats with red flaps, cuffs on their sleeves, and buckles made of lapis lazuli. While not presenting a scientific treatise, Sumpa Khenpo borrowed from European ethnographic tales and illustrations of the world to provide a remarkable vision of the planet that veered starkly from depictions that Tibetans were familiar with.

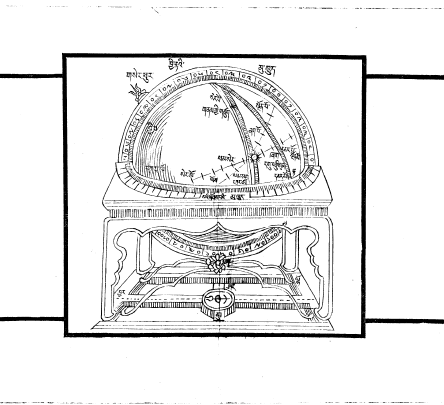

Completed in 1830, Tsenpo Nomonhan Jampel Chökyi Tenzin Trinlé’s (1789-1839) A Full Explanation of the World (‘Dzam gling rgyas bshad) explicitly built on Sumpa Khenpo’s General Description of the World. A Full Explanation of the World proved a pivotal work that, by blending Tibetan geography writing with a global geography, gave Tibetan monk scholars a vivid picture of the modern world outside of Tibet. Informed by encounters with Russians, a Pole, and a German as well as maps and travel logs from English, French, Portugese, and Jesuit works on geography in Chinese, Tsenpo Nomonhan’s book provided a tour de force of the globe with detailed descriptions of countries, peoples, and cultures. For instance, after describing clothing and fashion in Europe, Nomonhan also discussed technological inventions of the day, including glass tubes to measure chemicals, binoculars and telescopes to observe the stars, and celestial and global maps—objects unrecognizable to Tibetans in the 1800s.

This cosmopolitan impulse for new knowledge of the world was also reflected in Discourse on India to the South, an account of India and the West provided in 1788 by famed visionary Jikmé Lingpa (1730-1798).[3] The text shuttles between India, England, Holland, Rome, Beijing, and Śri Lanka to invite readers to think-up British ships, the musical contraption of the organ, a peep-show gadget as well as the fauna, flowers, and fruits of distant worlds. In doing so, it entices a kind of critical imagination that is at once skeptical of the outside world yet seeks to harmonize Buddhist canonical depictions of India with eye-witness accounts from Jikmé Lingpa’s principal informant, a Bhutanese diplomat who lived in Calcutta with the British for three years.

While largely based on foreign traveler accounts, these surveys of the 18th– and early 19th-century globe informed Tibetan scholars about world geography, which along with astronomy was the major branch of knowledge that directly informed their cosmology. By the early modern period, Tibetans were thus presented with European scientific ideas that directly challenged their Buddhist views of the world, time, and cosmos. Yet they were not mere recipients of this newfound knowledge, authoring works that detailed their understandings of world geography, informed their astronomy, and reformed their calendars. Tibetan scholars were knowledgeable about both theory and practice of European scientific paradigms, and wrestled with contradictory models of the world and cosmos presented by European science vis-à-vis their own historical cosmology. Their engagement with European scientific ideas demonstrates a concern for the discernible specifics of the sensorial world—a Tibetan scholastic concern not limited to this engagement—and a willingness to adapt to new knowledge that proved veridical, but they did not modify their whole vision of the cosmos based on this encounter.

To take these influences and their corresponding Tibetan writings seriously means to reframe the dialogue between Buddhism and science within its relevant historical context, which shows that Tibetan interlocutors were not naïve about European science prior to the mid-20th century. The fact that the history of science in Tibet stretches back centuries earlier than previous scholarship had conceived complicates multiple claims, namely that Tibet has long been a place isolated from foreign ideas, and that encounters between Tibetan Buddhism and Western science only occurred within the 20th century. It also calls into question the history of the Buddhist modernist narrative, which asserts that consequential encounters between European science and Buddhism began in the late 19th century. While scholarship on science in Tibet is nascent, these earlier encounters have far reaching implications for the current dialogue between Buddhism and science, the history of science in Tibet, and a global history of knowledge.

[1] The Tibetan Translation of Chinese Astrology Compiled by Mañjuśrī, King of the Heavens (i.e. the Kangxi Emperor), ‘Jam dbyangs bde ldan rgyal pos mdzad pa’i rgya rtsis bod skad du bsgyur ba. Unpublished Tibetan woodblock print.

[2] “’jig rten chags pa’i sa ‘di zlum po la nyi zla gza’ skar phal che ba zhig steng ‘og tu ‘khor zhing ‘gro bas bgrod tshul gyi dbang gis nyi ma zla bas sgrib pa dang zla ba sa gzhi nyi ma rnams thad drang por bab pa na sa gzhi’i grib ma zla lba phog pa’i dbang gis zla ‘dzin byung ba yin zer.”

[3] Aris, Michael. 1994. “India and the British According to a Tibetan Text of the Later Eighteenth Century.” In Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, 7-15. Edited by Per Kvaerne. Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture.

Michael R. Sheehy is a research assistant professor in Tibetan and Buddhist studies and the director of scholarship at the Contemplative Sciences Center at the University of Virginia. He is the co-editor of The Other Emptiness: Rethinking the Zhentong Buddhist Discourse in Tibet.

Featured Image: Gendun Chöpel, Round Earth Sketch, 1938. Courtesy of Columbia University Library.