by contributing editor Brooke Palmieri

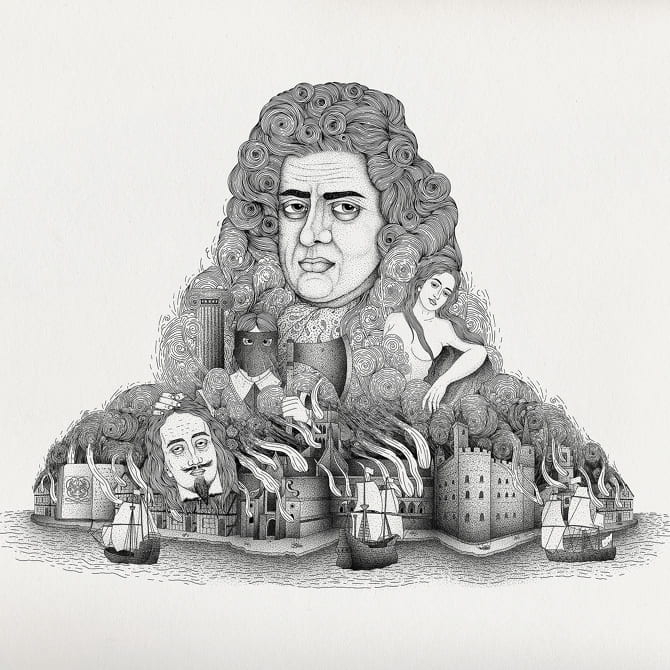

Pepys exhibition illustration by Bradley Jay

Few historical truths are as easy to pin down as the fact that Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) knew how to have a good time. He loved a good party, he loved his wine and his parmesan cheese, he loved to go to the theatre (350 performances in a 9 year span), and his enthusiasm for reading ranged from delight at Micrographia to erotic satisfaction at L’Ecole des Filles (although he burned it after reading).

As only we who are the most practiced hedonists can, Pepys made the best of bad situations. During an outbreak of plague in London he wrote in his diary at the end of July, while noting the death of around 1,700 people:

Thus I ended this month with the greatest joy that ever I did any in my life, because I have spent the greatest part of it with abundance of joy and honour, and pleasant journeys and brave entertainments, and without cost of money.

Or, during a boring sermon in Church, he simply took out his telescope and amused himself:

I did entertain myself with my perspective glass up and down the church, by which I had the great pleasure of seeing and gazing at a great many very fine women; and what with that, and sleeping, I passed away the time till sermon was done.

Hand-held telescope inscribed with name Jacob Cunigham, probable owner [Repro ID: F8641-001]

This exhibit has everything: a painting of the beheading of Charles I highlighted with a spotlight, draperies stimulating the houses of plague victims, recipes for avoiding the plague, Napier’s Bones, pirate catalogues, portraits of beautiful women (Nell Gwynn as Venus, Aphra Behn as herself), models of warships, mannequins wearing frilly Restoration fashions, ceramic tiles depicting the Popish Plot, elaborate drinking goblets, and multiple portraits Pepys commissioned of himself.

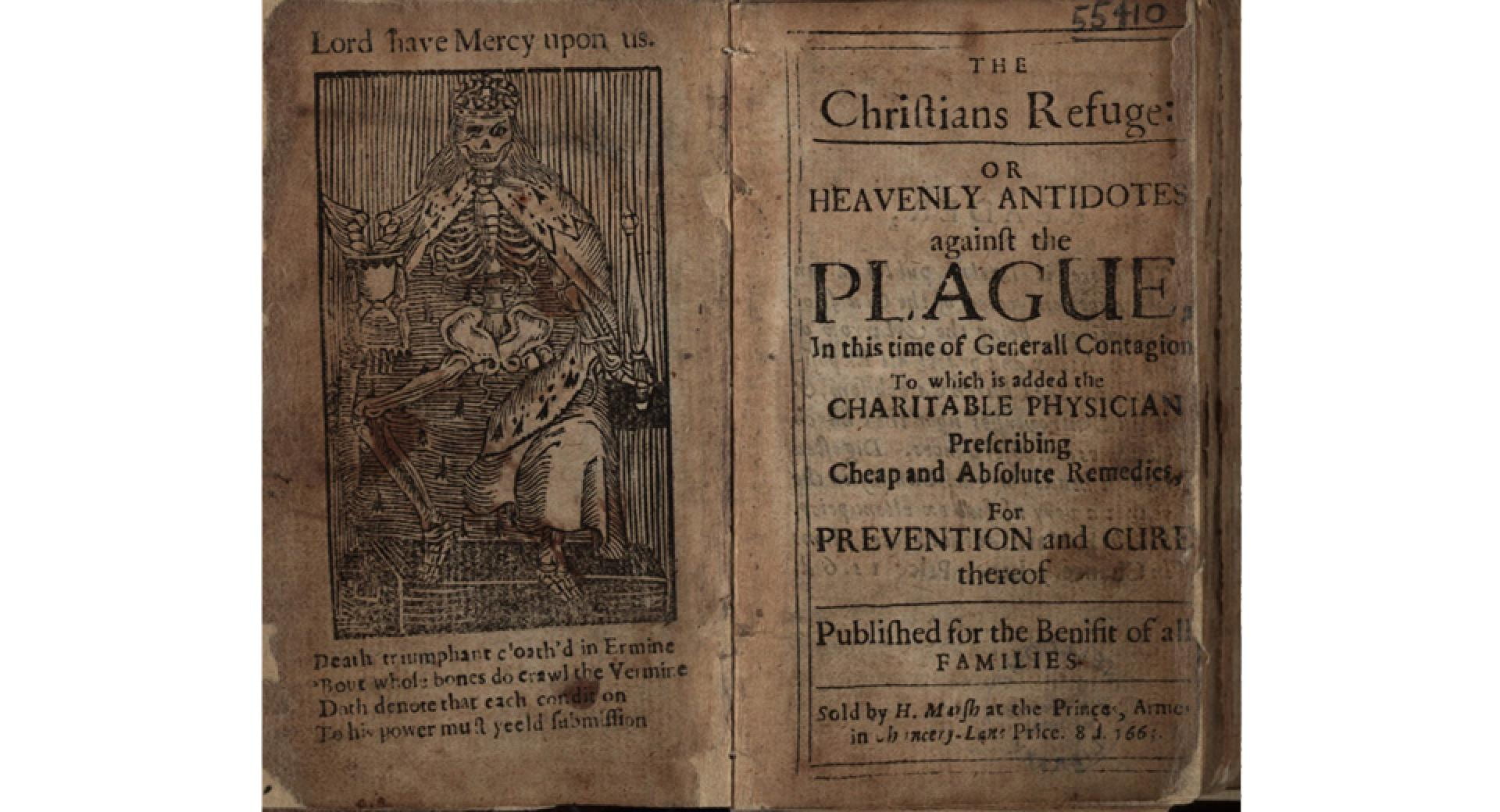

Frontispiece of EPB/53190/A: ‘The Christians Refuge’ Wellcome Images L0064305.

On the one hand, these materials offer an immersive experience into a well-worn concept of the Restoration dramatized in Pepys’ diary. As Lisa Jardine put it in a New Statesman review:

Because of Pepys, the Restoration has been painted with monotonous regularity as the age of the bodice-ripper adventure – men in periwigs doing shady business deals and exchanging confidences in crowded coffee houses, fondling buxom seamstresses and keeping covert assignations with neighbours’ wives, bedding loose women in insalubrious taverns.

But on the other hand, the exhibition intermingles that bodice-ripping with the traumatic highlights of the era Pepys survived (Revolution, Plague, and Fire). Wandering through the exhibition gives the impression that the periwig-wearing caricature of the Restoration Pepys has helped to popularise was a matter of psychological necessity — his own. Maybe the sheer weight of material accrued by the exhibition curators is a faithful re-enactment what a person of his social standing could do in 1666 to try to forget the pain of his own memories.

One of the first things Charles II did upon his restoration to the throne in 1660 is pass the Indemnity and Oblivion Act. Michael Neufeld among others has shown in The Civil Wars After 1660 how these acts kicked off a top-down effort to erase public memory of the Civil War (during which a fourth of the population perished) and Interregnum Period, and minimize violent reprisals. Under the act, only 11 out of the 31 regicides were executed, and records were altered, or ‘obliterated’ to erase any sourcex of embarrassment. But the government’s enforcement of memory loss and its related control on information and record-keeping could only go so far on a societal scale. Consider only for example the failure of the King’s supposed “Surveyor of the Press”, Sir Roger L’Estrange, toward the end of the 60s, in suppressing the publication of seditious materials among groups who had been vocal during the war — non-comformists like the Quakers barely broke their stride in speaking, and publishing, their minds. Against that background, acts of God were much more effective than legislation: pestilence that killed a fourth of London, a fire that levelled the city and incinerated many of its books, archives, and artefacts that people might otherwise use to connect with the past.

Who is to say how people might develop, on top of that, their own behaviours of forgetting, their own coping mechanisms: whether it be going to the theatre obsessively, or drinking wine constantly, or focusing their telescope on Jupiter and churchgoing ladies alike? Novelty can sometimes be deeply therapeutic, and in a London that had been destroyed, there was nothing to do but start over and buy garish new things until the panic subsided and there was truly the time to rebuild.

Fire of London, September 1666, British School, 18th century. (BHC0291)

This form of consumerist coping makes sense when paired with the epistemological optimism of institutions like the Royal Society, which Pepys was elected to in 1665 and president of in 1684: socialising around practices of observing new phenomena and conducting new experiments to re-calibrate an understanding of the way the world works is a wonderful way of moving forward. So too does it fit with his naval career and the expansion of the British Empire. The hunger for novelty to soften the traumas of the past seems, for Pepys, limitless. In The Invention of Improvement, Paul Slack describes it in different terms (indeed, in Pepys’ terms, or even at a later date Benjamin Franklin’s) that hunger becomes about “improvement” and “improvement came to rival and eventually replace alternative roads to better things, such as ‘reformation’ or ‘revolution’. Instead, the condition of England would be bettered by gradual and piecemeal change.”

That Pepys employed each of these strategies, and was involved in each of these scenes — cultural, scientific, political— is a testament to his privileged position: he had worked hard to make the money that allowed him to repeatedly make the best of bad situations. While he leaves an astonishing paper trail, one that makes it easy forget his limits as one man with one perspective (“History’s greatest witness,” the exhibition billboard proclaims), he is not alone in his habits or his emergency spending power. In that case: is the Restoration the first time in English history when it was possible to medicate trauma with material consumption? Did the combination of failed revolution, bubonic plague, and destructive flames create the ideal conditions for retail therapy? As Thomas Browne writes in the the preface to Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646): “Knowledge is made by oblivion, and to purchase a clear and warrantable body of Truth, we must forget and part with much we know.” Over-accumulation of new things serves a similar purpose. And walking through the exhibition has nearly that effect: the dramatic scenes of destruction at the beginning are almost blotted out by the lustre of fine cutlery and maritime instruments featured at the end. The pocket atlases and telescopes and seascape paintings that conclude the exhibition ask of us to look almost anywhere other than at the immediate surroundings, as Pepys himself seems to have done, with tireless optimism.

Samuel Pepys: Plague, Fire, Revolution is on at the National Maritime Museum, London, until March 28, 2016.

2 Pingbacks