by guest contributors Marcelline Block and Barry Nevin

World War I represented a loss of youth, innocence and ideals unparalleled in the twentieth century. Its initiation of mechanized murder and trench warfare laid waste to patriotic ideals, dismantled empires across Europe, plunged ill-equipped societies into a traumatized stupor, and formed a prelude to the unbridled ferocity of the Second World War. Diverse and multifaceted in its execution of warfare and in its consequences, World War I continues to haunt collective memory and to inspire imaginative endeavor in various forms of art, including poetry, fiction, music, and—most significantly for our purposes—film.

Modris Eksteins writes that World War I’s “agony is with us still. We cannot forget, nor can we ever truly comprehend” it (317). Building on Eksteins’ assertion and current writing on the relationship between WWI and cinema, we produced an edited volume, French Cinema and the Great War: Remembrance and Representation, in order to provide the first English-language book-length study devoted to representations of the First World War in French cinema from wartime society to the present day. It spans nearly one hundred years of filmmaking, from Léonce Perret’s Une page de gloire (1915) to Christian Carion’s Joyeux Noël (2005). We are interested in the various ways in which film mediates and transmits personal and collective memories and trauma of this crucial historical catastrophe through filmmakers’ engagement with contemporary political thought. Considering developments and deviations within the war genre, as well the relationship between the war and aesthetic style in French cinema, allows us to treat the relationship between French social, political, and cultural spheres throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and, by extension, to address evolutions in historical memory and the cathartic role of film in the expression of post-war trauma and memory.

We are interested in the various ways in which film mediates and transmits personal and collective memories and trauma of this crucial historical catastrophe through filmmakers’ engagement with contemporary political thought. Considering developments and deviations within the war genre, as well the relationship between the war and aesthetic style in French cinema, allows us to treat the relationship between French social, political, and cultural spheres throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and, by extension, to address evolutions in historical memory and the cathartic role of film in the expression of post-war trauma and memory.

From the earliest days of the cinematic medium to the twenty-first century, “la Der des Ders” inspired films as diverse as La Grande Illusion (Jean Renoir, 1937), Le Roi de Coeur (Philippe de Broca, 1966), La victoire en chantant (Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1976), Bertrand Tavernier’s La vie et rien d’autre (1989) and Capitaine Conan (1996), Un long dimanche de fiançailles (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2004), and Joyeux Noël (2005), challenging contemporary perceptions of European history and the boundaries of artistic expression.

For example, Joyeux Noël is based on true events of “a truce at Christmas on the Western Front” (9) and “real cases of Christmastime fraternization on the front lines” (262). The film depicts French, German, and Scottish soldiers in the trenches on the Western Front in 1914, during the first winter of World War I. Although the film’s director, Christian Carion, declares that he is “not a historian” and that Joyeux Noël is not a documentary, in attempting a “recuperation of the history” (220; translation mine) of this chapter of World War I—when enemy soldiers in the trenches dared to socialize together on Christmas—the film depicts, onscreen, “an incident long hidden from history” (66). Along with his film, Carion proposed “a scholarly work telling the true story of Christmas 1914 […] to coincide with the launch of his film” (10). This publication, Frères de tranchées—edited by French historian Marc Ferro with contributions by the British, French, and German scholars Malcolm Brown, Rémy Cazals, and Olaf Mueller—was published in 2005.

The publication of ‘Frères de tranchées’ coincided with the launch of Christian Carion’s film ‘Joyeux Noël.’

The English translation, Meetings in No-Man’s Land: Christmas 1914 and Fraternization in The Great War, appeared in 2006. According to Brown, this book “owes its existence […] to the intuition and vision of a young French film director, Christian Carion, a native of northern France, who somehow stumbled across the story which had taken place more or less on his own doorstep and saw the possibility of making a major film about it” (9).

The English translation, ‘Meetings in No-Man’s Land: Christmas 1914 and Fraternization in the Great War,’ appeared a year later in 2006.

Joyeux Noël’s treatment of real historical events that took place during World War I is just one example of how French film contains a complex repository of national collective memory and mourning about the Great War. It is also particularly amenable to reassessment due to its unique relationship with the trauma of war, alternately commemorating and stifling memories of the bloody combat in the years that followed the armistice. On one hand, films like Les Croix de Bois (Raymond Bernard, 1932), Le Roi de coeur (Philippe de Broca, 1966) and Joyeux Noël directly interrogate the war’s origins and consequences. On the other, in the decade of silent filmmaking that followed the armistice and in the twenty years following the end of the Second World War, French films were on the surface level conspicuously reticent regarding the Great War (with the exception of singular films such as Abel Gance’s 1919 J’accuse). But looking at the narrative setting and narrative style of cinematic representations of World War I allows us to interrogate the relationship between society and memory, and the former’s endless re-contextualization of the latter through time: in particular, through attention to gender, socio-political contexts, narrative style, and personal/collective trauma and memory of the First World War in French film. A wide range of filmmakers mobilized thematic and stylistic modes of expression to explore personal and collective memory of the war, creating texts that remain open to re-interpretation.

In the first instance, it is necessary simply to revisit and reassess many Great War narratives produced between the war years and the present day, some of which remain critically underappreciated. For instance, we bring renewed attention to Germaine Dulac’s use of newsreel footage in Le Cinéma au service de l’histoire (1935); the relationship between theatricality and power in Thomas l’imposteur (Georges Franju, 1965) and Le Roi de Coeur (Philippe de Broca, 1966); the dichotomy between physical and social space in Le Roi de Coeur; and how silenced, oppressed voices—forcibly conscripted colonial troops, members of the underprivileged social classes, and female victims of male violence—are represented in La victoire en chantant (Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1976), Capitaine Conan (Bertrand Tavernier, 1996), and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Un long dimanche de fiançailles (2004).

Another important aspect of French Great War films is the examination of representations of women as active contributors to the war, to local society during wartime, and to the preservation of memory in the aftermath of war. Particular case studies include Une Page de gloire (Léonce Perret, 1915) placed in dialogue with Cecil B. DeMille’s The Little American (1917); Un long dimanche de fiançailles (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2004), and La Vie et rien d’autre (Bertrand Tavernier, 1989) and Joyeux Noël examined in comparison. In each of these films, love functions as a potentially radical force: as a disruption of trench life and as a remedy to post-war trauma. Although “women’s First World War experience has played a lesser—often a non-existent—role” in studies of the Great War, “without women’s frame of reference, an analysis of the legacy of war remains incomplete, leading to the positing of universal statements in the name of only half the population” (1).

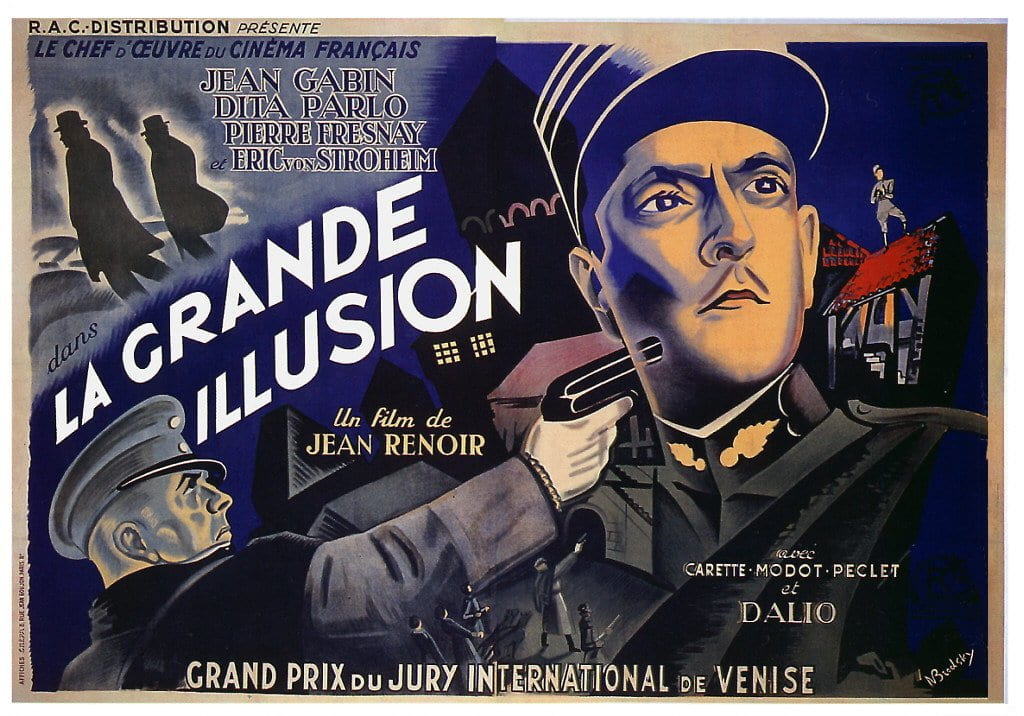

Of particular importance to our understanding of French cinema concerning World War I is Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion

. Renoir’s film is a core concern for three particular reasons: firstly, it was made during the twentieth anniversary of the war, as Europe drifted inexorably towards another war whilst others clung desperately to a pacifist stance; secondly, Renoir himself had fought in the Great War, and stood as a living embodiment of post-war trauma; thirdly, and most interestingly, the film salutes fallen soldiers through its very portrayal of POWs and bereavement, but simultaneously challenges notions regarding commemoration through its dialogue and mise-en-scène. Because of the numerous stances embedded in Renoir’s complex narrative style, the extent to which the film alternately laments, commemorates and foreshadows war in a manner that demands reassessment.

. Renoir’s film is a core concern for three particular reasons: firstly, it was made during the twentieth anniversary of the war, as Europe drifted inexorably towards another war whilst others clung desperately to a pacifist stance; secondly, Renoir himself had fought in the Great War, and stood as a living embodiment of post-war trauma; thirdly, and most interestingly, the film salutes fallen soldiers through its very portrayal of POWs and bereavement, but simultaneously challenges notions regarding commemoration through its dialogue and mise-en-scène. Because of the numerous stances embedded in Renoir’s complex narrative style, the extent to which the film alternately laments, commemorates and foreshadows war in a manner that demands reassessment.

Still from ‘La Grande Illusion.’

In particular, a complex analysis of the narrative’s semi-autobiographical portrayal of gender, disability, and heroism can demonstrate how La Grande Illusion becomes a metaphor for the inherently problematic nature of commemoration. The context of the film’s production shows how certain elements of a filmmaker’s personal memory can enter into dialogue with collective memory, producing new reflective narratives that complement as well as challenge society’s exigencies.

We’ve edited our volume in order to coincide with the hundredth anniversary of the Great War. Its exploration of French cinema is timelier than ever since first-hand experiences of the war have now been definitively buried: Lazare Ponticelli, who lived to be 110 years old, was the last French poilu to die, on 12 March 2008; Harry Patch of the British Army, the last veteran to have served in the trenches, died on 25 July 2009 at the age of 111; and Claude Choules of the British Royal Navy died on 5 May 2011, aged 110. We aim to broach issues such as developments and deviations within the war film genre, the relationship between the war genre and aesthetic style and, on a broader level, the continued significance of World War I to contemporary French social, political, cultural and cinematic spheres throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Marcelline Block’s publications about cinema include World Film Locations: Paris (Intellect, 2011), Filmer Marseille (Presses Universitaires de Provence, 2013), and French Cinema in Close-up: La vie d’un acteur pour moi (Phaeton, 2015), which Library Journal named a Best Print Reference work of 2015.

Barry Nevin (BA, PhD) currently lectures on French and film studies at NUI Galway. His research on Jean Renoir’s La Chienne will be published in Urban Cultural Studies (Intellect) in March 2016, and his examination of Renoir’s pro-colonial propaganda will be published in Studies in French Cinema (Taylor & Francis) in July 2016.

March 9, 2016 at 2:43 pm

This was absolutly excellent – shared in our Facebook page.

I’m a sucker for French cinema and history and this just puts it together very nicely.

http://www.wuhstry.wordpress.com

December 10, 2017 at 11:31 am

J’aime le cinéma français! Il montre toujours le jeu magistral des acteurs et l’intrigue réfléchie. Et pour les fans du cinéma français c’est une opportunité très utile et gratuite de regarder des films intéressants ici: https://papystreaming.video/ Impatient d’attendre de nouveaux films!