By George Townsend

Scholars have made significant strides in recent years towards decentring colonizing and ruling class perspectives in their accounts of historical swimming and bathing practices. Margaret Roberts and Dave Day have delved into the lives of the Victorian swimming professors – men and women who often taught at private schools and universities but were also key players in lively working-class communities oriented around physical prowess, competition and spectacle. Kevin Dawson’s groundbreaking Undercurrents of Power, meanwhile, explores West Africa’s rich history of swimming and the ways in which enslaved Africans carried aquatic cultures with them to American colonies – paving the way for further study of the resilience of swimming and bathing practices among non-Western and colonized peoples. At the same time, the bathing place itself remains relatively under-examined. The concept of the bathing place was applied in dramatically different contexts, both at the heart and in the peripheries of of colonial geography: from the grounds of English public schools where prospective colonial administrators were socialized, to the riversides of countries like Sri Lanka, where traditional bathing practices persisted under colonial rule. How can a comparative approach to these sites of communal outdoor bathing, and an approach open to their representation in a variety of sources, from scientific texts to picture postcards, contribute to our critical understanding of the colonial imagination?

On the one hand, the bathing place figures as a site of colonial voyeurism, where the anthropological gaze penetrates a zone of tenderness and play – a space where non-Western societies can supposedly be viewed and interpreted in their most frank and unmediated states. In Havelock Ellis’s ‘The Evolution of Modesty’, from the first volume of his highly influential Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1897-1928), the bathing place repeatedly appears as a site that registers the ‘modesty’ of native peoples – and particularly of women, in whom Ellis adjudges modesty to be almost the “chief secondary sexual character”. “In Ceylon,” writes one of Ellis’s correspondents,

a woman always bathes in public streams, but she never removes all her clothes. She washes under the cloth, bit by bit, and then slips on the dry, new cloth, and pulls out the wet one from underneath (much in the same way as servant girls and young women in England).

Deploying a social evolutionary framework, in which the practices of “primitive peoples” from across the globe are uncritically identified with those of European ancestors, Ellis presents modesty at the bathing place as a form of cultural backwardness. Classical baths where men and women bathed naked together feature, by contrast, as the pinnacle of human body culture. Within Ellis’s account this frequently results in an upturning of nineteenth century stereotypes about the relationship between savagery and immodesty. The moral reformer Joseph Livesey complained in 1831 against the naked bathers at Lea Marsh in Northeast London: “Unrestrained either by principle, custom or authority, the scenes exhibited are just what might be expected from savage nations”. On the contrary, Ellis suggests, principle, custom and authority are everywhere to be found, even if they do not match up to the principle, custom and authority of the English moral reformer.

Ellis nonetheless maintains a hierarchical, Orientalist perspective, measuring cultures according to their perceived advancement or decline. According to this view Europe had – when it came to sex, nudity, and public bathing – been dragged back into an unenlightened state through the stifling prudery of the Church. Ellis’s most striking exemplar here comes from Saint Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, writing in the third century to chastise women who bathed promiscuously with men:

Such a washing defiles; it does not purify or cleanse the limbs, but stains them. You behold no one immodestly, but you, yourself, are gazed upon immodestly … in delighting others you yourself are polluted; you make a show of the bathing-place; the places where you assemble are fouler than a theatre … Let your baths be performed with women, whose behavior is modest towards you.

In reaction against such ideas, which progressive critics such as Ellis regarded as symptomatic of organized Christianity across the centuries, the fin-de-siècle bathing place became a petri dish for assessing, and possibly addressing, wider societal progress and decay. Ellis notably became an advocate for the “moralizing and refining influence of nakedness” as part of education – an idea taken up contemporaneously at schools such as Abbotsholme and Bedales (founded 1889 and 1893 respectively) that guided their pupils “back to the land.” There, open air bathing was, according to historian Jan Marsh, “almost an article of faith”.

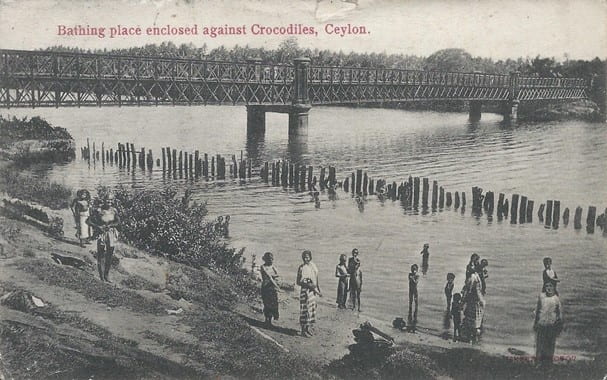

The idea of the bathing place as a social petri dish was active at a more popular level, too, through the ephemera of empire. A picture postcard sent in August 1909 to an address in Hull, England, depicts a bathing place at the foot of a bridge, which is shown extending across the Kelani River in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Thick wooden staves, driven into the riverbed, form a stockade in the water, and a caption in red accompanies the image: ‘Bathing place enclosed against Crocodiles, Ceylon.’ Women and children stand in and around the water, facing the camera. The women wear clothes, the children are largely naked. The photographer, or somebody developing the picture, has doctored one figure in the bottom right-hand corner, drawing over their face and possibly their dress after the photograph was taken. The rectilinear metallic structure of the bridge contrasts with the higgledy-piggledy line – like so many uneven teeth – of the enclosing palisade. The bridge was completed in 1895 and named after Queen Victoria. “Ceylon grand place for half day trip,” writes ‘Bert’, the sender, with the ambiguous sign-off, “Good fishing evidently.”

In the same period, the bathing place had another very different face, featuring in several texts as an embodied, almost umbilical link to home for Britain’s colonial actors. The protagonist of Rudyard Kipling’s short story “To Be Filed for Reference”, which is set in India, drunkenly recalls using cold dips at “Loggerhead” as a hangover cure in his student days. In the nineteenth century, Loggerhead was an alternative name for Parson’s Pleasure, a bathing place active on the river Cherwell outside Oxford for several centuries. After 1865, when the site was enclosed and the entry fee increased from a penny to 4p for men and 3p for boys, Parson’s Pleasure was largely appropriated by affluent citizens and members of the university. With a more reverential tone, a 1922 article in the Pall Mall Gazette tells the story of how T. E. Lawrence (who grew up in Oxford) was “fetched up from the bottom of Parson’s Pleasure” as a child, indicating that he bore a “charmed life.” The diplomat Sir Francis Lindley (1872-1950), meanwhile, concludes a roving account of his bathes around the world – in the Pacific, the Bosphorus, the Mediterranean,

If those in advancing middle age reflect on their bathing careers … they will think in their hearts that nothing can ever quite equal a morning plunge in Parson’s Pleasure, in Gunner’s Hole, or Cuckoo Weir [bathing places associated with Winchester and Eton]. For many these names hold a magic not to be exorcised by the voice of reason or of experience.

Parson’s Pleasure and similar sites excluded working-class bathers and women, even as they relied on female and working-class labor in the form of attendants and laundresses. In these texts they nonetheless appear as remembered idylls with a deep affective power. Emblematic simultaneously of England and childhood, they began in the second half of the nineteenth century to represent for colonial agents and commentators both a rite of passage and a perennial source of nostalgia.

This side of the bathing place bears some similarities to the playing field of the English public school, with its emphasis on the body, male sociality, play and memory. Yet ideas about the benefits or pitfalls of the bathing place – and specifically its prevalent use as a site of communal bathing for male pupils – are far less evident in historical debates about education, and indeed in subsequent historiography. In the early days of Marlborough College in Wiltshire (founded 1843) the bathing place was, according to one alumnus, a “large pond some 80 yards long and 15 wide.”

The depth was graduated from the ‘duck-pond’ to the deeper depths, where advanced swimmers took ‘headers’ off spring-boards, and otherwise disported themselves … There was no lack of teachers, in every case self-appointed, who … would take no refusal. The hapless pupil was seized by the arms and legs by two big fellows, and with one – two – three – and away, hurled into the middle of the pond, to find his way out as best he might … It was of a piece with the rough-and-ready education of those days, which helped boys become resourceful men.

Bathing places such as this were not only locations for learning to swim, but also formed part of the educational ideology that became known as muscular Christianity, turning boys into men capable of defending and expanding the Empire. By the early 1900s, the pond had been supplanted by a new pool in the river Kennett, a photograph of which was taken for Frank Sachs’s The Complete Swimmer, published 1912. The photograph, reproduced here as a postcard, makes for a striking counterpoint to the postcard from Sri Lanka.

Straight formalized banks contain the bathing place to left and right. The water is void of bathers, the banks populated not by local women and children but service staff from the College, uniformed in flat caps and in one case a white apron. Through this configuration, the image seems to invite and flatter the viewer, the water offering itself up for refreshment and exercise, attendants ready at hand to instruct and protect. Far from nature posing any threat, it is in these controlled, amenable conditions that natural forces are mastered, the only hint of animal life looming in the background, barely visible: the chalk figure of the Marlborough White Horse on the hill.

George Townsend is a PhD candidate in English at Birkbeck, University of London, where he is studying the cultural history of public bathing places, focusing specifically on the history of Parson’s Pleasure, Oxford.

Featured Image: A postcard showing a bathing place on the Kelani River in Colombo, Sri Lanka, c. 1909. Source: personal collection.