Karie Schultz is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of St Andrews (2021-2024) with research interests in the relationship between theology and political thought in early modern Britain and Europe. Her current project examines seventeenth-century Catholic and Reformed student mobility from the British Isles to Europe with a specific focus on confessional and national identity formation. She completed her PhD at Queen’s University Belfast in 2020, followed by a nine-month fellowship at the British School at Rome. Her first monograph, Protestantism, Revolution and Scottish Political Thought: The European Context, 1637-1651 is forthcoming with Edinburgh University Press.

Schultz spoke with contributing editor Pranav Jain about her essay “Protestant Intellectual Culture and Political Ideas in the Scottish Universities, ca. 1600–50,” which has appeared in the current issue of the JHI (83.1).

***

Pranav Jain: I appreciated the point in your article that historians should look beyond printed sources, especially to student notebooks and theses. Apart from the themes that you have covered in this essay, what else can we glean from such sources about early modern universities and other subjects?

Karie Schultz: Although sources from the early modern universities—student notebooks, lecture notes, disputations, and philosophical theses—are linguistically and paleographically challenging, they are highly valuable for several reasons. First, they provide critical insights into multiple aspects of university education in the early modern period. Although I use these sources in the article to examine the teaching of ethical and political doctrines, this material provides information about other university subjects (philosophy, theology, logic, and metaphysics). They are an incredibly rich source base for understanding how Scottish intellectual culture developed across multiple disciplines, and they help us situate Scotland within broader European intellectual trends. Lecture notes, student notebooks, and theses also reveal similarities and differences in how regents taught their students about philosophical, theological, and ethical doctrines. They demonstrate how multiple strands of Protestant thought arose within a shared Aristotelian curriculum, especially as Scots attempted to forge a confessional orthodoxy after the Reformation of 1560.

Second, although this article focuses specifically on the Reformed universities and Protestant intellectual culture, such sources also exist for Catholic institutions across Europe. For example, lecture notes, student notebooks, and disputations survive from the Collegio Romano (the precursor to the modern Pontifical Gregorian University), a Jesuit-run institution that trained Catholic students of different nationalities who came to study in Rome. Upon completing their education, these Catholic students took up careers of political or religious prominence, often in diplomacy, the mission field, or the priesthood. An emphasis on Aristotelian texts and a sustained interest in doctrines about civic life (similar to those advanced in sources from the Scottish universities) also appeared within lecture notes and student notebooks from the Collegio Romano. These sources therefore provide a valuable perspective on similarities and differences in how Reformed and Catholic students were educated to think about politics, theology, ethics, and philosophy in the early modern period.

Lastly, these sources are valuable beyond the university context and help us to better understand the transmission of ideas on a broader social basis. While printed works instrumentally shaped public opinion and created spheres for popular debate in the early modern period, focusing only on printed texts provides little analysis of how religious and political orthodoxies were taught to a significant proportion of the population. The focus on printed works has thus left a fundamental gap in our understanding of early modern intellectual culture, especially regarding how university-educated individuals thought about political duties in a century dominated by instability and civil strife. Furthermore, early modern universities were wealthy, powerful, and culturally significant institutions. Like their Catholic contemporaries, students in Reformed universities frequently took up prominent positions in the community as statesmen, diplomats, lawyers, ministers, or university regents. Through these positions, they could transmit the ideas they learned in the universities to the wider population through sermons, print, and ordinary conversations. For this reason, examining the doctrines that university students were taught about ethics, philosophy, and theology (whether in Scotland or beyond) is essential for understanding the establishment of confessional and political orthodoxies after the Reformation.

PJ: Both historically and historiographically, does your interpretation of Protestant intellectual life in the early seventeenth century apply to educational institutions beyond Scotland, especially those in continental Europe?

KS: Yes, the interpretation of Protestant intellectual life that I advance in the article—one characterized by complex Augustinian and Aristotelian strains of thought about human engagement in politics—applies to educational institutions beyond Scotland. Reformed universities across Europe had a shared Aristotelian framework for the curriculum, even though methodologies might differ. Students educated in European institutions engaged with the same philosophical, theological, and political ideas as students educated in the Scottish universities. Although historians of the Scottish universities have long confronted the misconception that these institutions were intellectually stagnant prior to the Enlightenment, we are increasingly acknowledging that they operated on the cutting edge of the philosophical and theological debates taking place within the British Isles and in continental Europe. Early modern universities were also highly transnational with significant amounts of student mobility. Students from Scotland frequently traveled abroad to receive part (if not all) of their education at universities in Europe. For example, John Forbes of Corse, the leader of the so-called ‘Aberdeen Doctors,’ studied at Heidelberg under David Pareus where he began to develop his ideas about religious irenicism and the unification of the Protestant nations of Europe. The movement of students and regents across the continent meant that the students and regents at the Scottish universities participated in a shared Protestant intellectual culture that extended beyond their own borders.

Furthermore, the political and ethical doctrines considered by students and regents in the Scottish universities have connections to broader Reformed intellectual traditions across Europe. Scholars have long been interested in the relationship between early modern Reformed intellectuals and the political ideas underlying the modern secular state. In this article, I argue that complex Augustinian and Aristotelian strands of thought about human nature and political life permeated university education. Even though students in Scotland studied at confessionalized universities and were taught Reformed theology, they were not predetermined to think about human nature and the purpose of the temporal kingdom in one specific way. This was also certainly the case in Europe where Reformed students received a similar education in theology, philosophy, and ethics which resulted in multiple perspectives on human nature and political life. Importantly, this challenges the notion that there was one consistent body of Reformed political thought emerging from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that laid the foundations for the modern secular state.

PJ: At the end of the essay, you suggest that “the teaching of ethics and politics within the Scottish universities therefore provided students with a variegated intellectual framework for approaching political life, one that they adapted to create their own languages of political legitimacy during the civil wars of the 1640s.” Can you elaborate on what these languages were, and whether they survived the upheavals of the civil wars?

KS: One primary purpose of university education in seventeenth-century Scotland was to teach students how to live as good and godly subjects in the temporal kingdom. Above all, Scots aimed to establish a nation covenanted with God, and they used university education to instill godly values in their students. However, what it meant to be a godly subject who obeyed God’s commandments for political life varied for Scots, especially during the civil wars of the 1640s. On the one hand, some Scots emphasized human depravity and the need for obedience to civil government, a position that reflected the profound influence of Augustinian ideas on Reformed intellectual culture. Many Scottish royalists, such as John Maxwell, the Aberdeen Doctors, and John Corbet, argued that God ordained government to control human sinfulness and wickedness. As a result, subjects had a primary duty of obedience in the temporal kingdom, whereby they obeyed all laws and the king as God’s regent on earth. Such ideas about obedience and passivity in political life, ones which were derived from viewing government as a tool for restraining sinfulness, thus resonated with the Augustinian emphasis on human depravity that circulated in the Scottish universities.

On the other hand, many Covenanter leaders embraced a form of limited or constitutional monarchy, whereby Parliament and civil law ruled above the king. They emphasized rational human participation in political life, arguing that God allowed human beings to mediate his original power by electing and deposing their magistrates using their reason. The king’s power was legitimate only insofar as he upheld his covenant with God and the people to be a godly and just ruler. If he failed to do so, God called subjects to resistance and active engagement in reconstituting governments. The different perspectives on human nature and political participation that were discussed in the universities therefore gave royalists and Covenanters the language necessary to debate the legitimacy of political authority during the civil wars. The political ideas that emerged from these conversations (absolute sovereignty, consent of the governed, the right of self-defense) are now regarded as the building blocks of the modern secular state. As such, the languages of political legitimacy advanced in the civil wars (ones which were intrinsically connected to the teaching of ethics in the universities) persisted beyond the 1640s, making an awareness of how ideas about human engagement in political life were taught in the universities all the more vital.

Pranav Jain is a PhD student at Yale University working on early modern Britain, and a contributing editor at the JHI Blog.

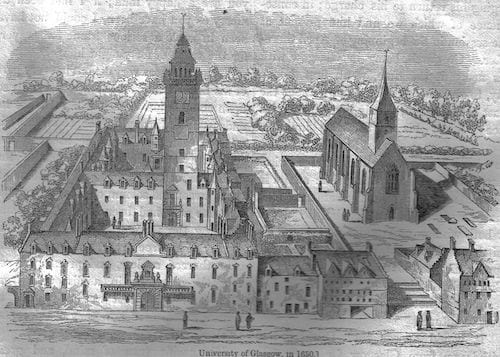

Featured Image: Glasgow University around 1650. From James Howie, The Scots Worthies (1876). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.