By Manaswini Sen

The rise of authoritarian regimes across the world in the last few decades demands meticulous re-evaluation of the genesis of “authoritarianism” as a system. Considering that the nature and face of fascism have changed considerably over the course of the twentieth century, Ian Kershaw has commented that, “Trying to define “Fascism” is like trying to nail jelly to the wall.” The erstwhile dictators of early twentieth century have given way to our present day strongmen. These politicians have established their totalitarian regimes as leaders of conservative parties which have managed to garner electoral hegemony. This has in turn caused a veritable crisis evident through curtailment of free speech, and a systematic erasure of dissent rendering any sort of opposition a virtual impossibility. Therefore, not only is it imperative to revisit the rich corpus of anti-fascist literature, but it is also crucial to analyze its vernacular reception and reconceptualization, in the works of Indian anti-colonial, and anti-capitalist political thinkers such as Saumyendranath Tagore. This piece contemplates how anti-colonial narratives from the Global South transcended the narrow confines of nationalism, as anti-Fascism and communism was getting intimately entwined with the vision of decolonization generating a truly global discourse.

Tagore was born in 1901 and belonged to the elite upper caste-class group of intellectuals in colonial Bengal, known as the bhadralok. He was the grand-nephew of the renowned poet, artist, and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, and because of the tremendous cultural capital which the Tagore clan offered him he was trained in performing arts and literature. The Tagores represented a strong voice of dissent against the colonial injustices. The pen was their preferred weapon of offensive; however Saumyendranath broke this stereotype when he joined active mass politics during the heyday of the Gandhian Non-Cooperation Movement in the 1920s. His disillusionment with the movement was inevitable as it was called off in 1922 over a spontaneous incident at Chauri Chaura, Gorakhpur in Bihar where a group of protesters were fired upon by the police and in retaliation they set the police station on fire killing all its occupants. . Tagore belonged to the newer brand of trade union vanguards who were caught up in the ebb and flow of mainstream anti-colonial struggle characterized by the Indian National Congress which was essentially a bastion of upper-caste Hindu bhadralok. The general disillusionment with appeasement politics laced with heavy overtures of Hindu revivalism and enchantment towards a new egalitarian world pushed them towards communism. Their transformed political ambitions and visions barely found any niche in an organization hegemonized by upper-class bureaucrats, barristers, and white-collar clerical conglomerates. This disenchantment ensued his acquaintance with the “Language of the class”. He chanced upon a journal with a fairly unwonted name while traversing the by lanes of Harrison Road in North Calcutta. The unusual nomenclature, Langal (The Plough) triggered his interest, and by writing a letter to its editor, Shamshuddin Ahmad, Tagore’s tryst with Indian communism began. Soon after he joined The Labour Swaraj Party in 1925, Tagore was on the radar of the intelligence officers as “a zealous and dangerous Communist and revolutionary”. However, the Commissioner of Bengal Police, Charles Tegart knew that there would be tremendous public criticism of the British government, if they arrested a member of a Tagore family. In May 1927 Saumyendranath left for the Soviet Union where he attended the Sixth International of the Comintern in 1928. He left for Berlin right after, where his close association with the League Against Imperialism and direct exposure to contemporary European politics led to the sagacious comprehension of the multifarious ways in which “ultra nationalism” can manifest itself and exacerbate the social inequalities besides the political and economic ones.

Saumyndranath became a prolific writer engaging himself in active propaganda against Nazism during this time. The transcontinental ties and the budding solidarities to combat the rising tide of fascism marked an epoch of vibrancy in intellectual and ideological exchange. The inexorable repression from the Gestapo and the Nazi state culminated in his arrest in 1933 on the absurd ground of conspiring to assassinate the Fuhrer. After his release from the prison in Munich, he headed straight to Paris. Paris in the 1930s was a refuge to exiled revolutionaries from different corners of the globe. Notwithstanding the heterogeneity of the range of their ideological adherence, erecting a proletariat front against fascist onslaught was the call of the times. In the bid to counter fascism with communism he became overtly active in the Anti-fascist circles of Paris. These intellectual encounters shaped his political thought and praxis profoundly. The year also marked the release of Hitlarism: the Aryan Rule in Germany, an anthology of his essays written between April and December, divulging the sinister face of Nazism and the racial apartheid engendered by it.

In the article, Who Paved the Way for Fascism in Germany?, he highlighted how the German socialists had betrayed the interests of the working-class. In the garb of stabilizing the economy of the country after the First World War, they had systematically deprived workers of their basic rights as unemployment and fall in the standard of living became rampant. This essay was a scathing attack on Socialists like Ebert Noske and their pivotal role in the assassination of dissenting communist voices like Karl Liebrecht and Rosa Luxemburg. He critiqued the counter-revolutionary nature of the Socialists and pointed out their capitalist roots which caused them to launch a flagrant onslaught on the communists. Their sheer apathy towards the downtrodden led to the displacement of the International theory of ‘solidarity of the working class’ with the bourgeois theory of ‘solidarity of all classes’. Tagore, like many of his contemporary socialists and communists were conflicted on the question of class collaboration with the Bourgeoisie to launch any revolutionary struggle due to the intrinsic dialectical relationship between the classes, denouncing the theory of “solidarity of all classes” against “solidarity of the working class”. What transpired was the most vicious of crimes against humanity orchestrated by the authoritarian German state in the form of Anti-Semitic violence. In his speech delivered at a protest meet in Paris around September 1933 against the Reichstag Fire, Tagore emphasized that racial bigotry against Jews served two specific purposes, ‘one is to divert the class struggle of working-class into blind alleys of racial struggle’, and second was holding the Jews accountable for the economic distresses of the German mass. He described the Nazi regime as a diabolical ‘racial cannibalism’ and called for condemnation by any “civilized individual”. Scholars have dealt with his views on Nazism whilst assessing the broader Indian intellectual response to, and ties with, the Third Reich. However his deliberations on Italian Fascism often get overlooked in these works though, his monograph titled, Fascism (1934) written in Bengali, was one of the earliest Bengali critiques of an authoritarian state. This tract encapsulates conscientiously his perspective on fascism anchored in Imperialism, expansionism, and ultra nationalism (‘ugro-jatiyotabad’). Through a careful dissection of the body politic of the Italian fascist state, he analyzed how Fascism effectively used jingoism, and insecurities of the petty bourgeoisie to create and legitimize a centralized government which aimed at erasing individual dissent and agency. In the preface, he writes,

with the imminent crisis of the 20th-century dawning upon us never before in the history of mankind the world has been polarized into two specific camps: the Communists and the Bourgeoisie. Despite coming from disparate backgrounds all sections of the bourgeoisie ultimately have the common goal of saving capitalism, and hence pits itself as the class enemy of the proletariat. As the decisive moment of the Working-class revolution is nearing, the insecurities among these various sections of the Bourgeoisie are making them endorse various fascist groups. The days of saving capitalism through bourgeois liberalism are long gone. Hence, they have given up the facade of democracy and liberalism and have resorted to the use of brute force. (Tagore, Fascism, p.7)

His ‘longue duree’ approach towards analyzing the genesis of fascism can be seen in his essay, Mussolini, in which he makes a comparative study of the dictator’s writing before and after the initiation of The First World War(1914-19). By looking at Mussolini’s pieces in socialist mouthpieces like Avanti and later Il Popolo d’Italia, Tagore illustrated how he used the veil of socialism to win the trust of the working-class and recruit them in an imperialist bourgeoisie war to serve the interests of their class enemies. He advised the masses to stay neutral during Italy’s war efforts against Austria in the initial days, but by the end of 1914 he engaged in vigorous war propaganda inciting popular sentiments through the tool of ‘patriotism’ and ‘love and sacrifice for the motherland’. The anthology stands out owing to its range, encompassing theoretical rumination on fascism as well as analysis which emerged from his punctilious observations of the regime during his stay in Italy. Critiquing Mussolini’s false claim that he will improve the standard of living of the Italian mass, despite the Global Depression of 1929, Tagore wrote Fascism and the Labor-Peasant problem. The essay is not only contingent upon statistical data but also a testament to how political praxis and political thought shape one another. He pointed out that smaller cities like Naples were swarmed with destitutes in public places, whilst Rome, the capital, had its streets sanitized of such manifestations of poverty and pain. The Italian Government had orchestrated the coerced evacuation of the streets of Rome, and it was made out of bounds for beggars. He unmasked the true nature of the fascist state as it continued to engage in false propaganda maintained an outward show of political might, while the economy was plummeting. In Tagore’s eyes, “the deplorable state of the working-class living quarters” in Naples, was comparable to the “indigence in a colony, like India”. (Fascism, pp. 56-57)

Tagore implemented fascism as an analytical tool to comprehend colonialism and the systematic inequalities engineered by it. Introspected through the twin lenses of militarism and expansionism, he expounded how cultural movements such as Futurism aggravated the existing crisis caused by colonialism along with fascism. Tagore, encountered the Italian futurist figurehead, Filippo T. Marinetti, and extensively engaged with the Futurist Manifesto which upheld and celebrated war as the sole source of regeneration for a moribund nation. This proposition made Tagore conclude how fascism was the perfect tool in the hands of warmongering capitalists to forward their colonial extractivist designs. He remarked,

‘Futurism, far from insinuating cultural efflorescence have been commemorating anti-intellectualism and anti-egalitarianism since decades. The only difference being they are doing it adorning the fascist blackshirts now’. (Fascism, p.72)

Throughout the length of the book, Tagore interrogated extensively how fascism and colonialism were intricately connected and analysed the ways in which the trope of ‘mystic nationalism’ was conveniently appropriated to justify brazen expansionism.

Tagore never saw the rise of fascism in isolation or as a strictly European phenomenon and stressed upon the possibility of upsurge of this vicious trend within the anti-colonial struggle in India. He dreaded the efforts towards national liberation which elicited from unfettered and uncritical patriotism. Referring to professors from Calcutta University like Promotho Roy and Sunitikumar Chattopadhyay and their efforts at translating the speeches of Mussolini and eulogizing him, he was unveiling the reactionary nature of the Nationalist Bourgeoisie. The sojourn in Europe further nuanced his vision on trade unionism, a discourse that primarily emerged as a fierce polemic against Gandhian mass politics embedded in the rhetoric of spiritualism and non-violence. Saumyendranath wrote, Gandhism and the Labour Peasant Problem, in Europe commenting on the absurdity of the Gandhian tactics of arbitration as the ideal strategy for wage bargaining instead of striking. Drawing a parallel between the German state under the Social Democrats at the verge of transforming into a fascist state and their coercive action which made arbitration compulsory and Gandhi’s enticement with the same, he stressed how Arbitration was becoming ‘a mighty weapon in the hands of the capitalists’. The critical insight that the Gandhian tenet of ‘class collaboration’ was intrinsically flawed as dialectically the two classes harbor opposite interests was a reflection of his interaction with officials of fascist industrial trade unions in Italy. Tagore divulged how these unions were instrumental in the depletion of the ideal of ‘class struggle’, and supplanting it with one of collaboration and total submission to the profit-driven whims of the capitalists through systematic propaganda.

One might argue that Fascism, was simultaneously published with British communist R.P. Dutt’s Fascism and Social Revolution and coincided with the occurrence of the 17th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, which officially considered fascism as a terrorist onslaught of the most vicious of the reactionary capitalists, and reflected similar arguments as that of Tagore’s. However, Saumyendranath far from being a full-fledged left theorist was a labor activist, whose appraisals emanated from his first-hand encounter as a colonized subject in the European heartland of fascism. Hence, it was a veritable local response to a global crisis, where the employment of the vernacular, riddled with scintillating metaphors was making Tagore’s ideas accessible to a wider population. His endeavor democratized the constricted space of ideological introspection monopolized by the anglicized upper-class intellectuals.

Tagore’s crusade against fascism found expression in his effort to open a branch of League Against Fascism and War in India in 1936, when Spain was ravaged by a horrific Civil War insinuated by fascist elements in the country. Addressing several working-class meetings he stressed how the Spanish struggle for democracy was an extended fight for Indian independence. In a conflict where the revolutionary was pitted against the reactionary, he called for collective action by the workers, peasants, and youths from India against it in a bid for manufacturing internationalism from below. Saumyndranath’s discourse on fascism transcended the confines of nationalism as proletarian internationalism was his answer to the onslaughts of totalitarianism. The most enduring of his contribution, however, is the provision of an alternative vision of anti-colonialism, which is grafted not in the orthodox trope of nationalism. Saumyndranath’s anti-fascist championing thus indeed led to the recovery of globalism within a history of eternal localism.

Manaswini Sen is an early career researcher and a Ph.D. candidate currently enrolled at the University of Hyderabad, India. Her thesis, tentatively titled, ‘The Unsettling Decades: Mapping the Changing Trends in the Trade Union Movement of Late Colonial Calcutta (1930-1947)’, will help in establishing why the period between 1930 -1947 was a decisive break in Labour Politics of Bengal and how it finally turned into a full-fledged radical Trade Union Movement. Her research interests straddle the fields of Labour History, History of Decolonisation in South and Southeast Asia, Intellectual History, History of Surveillance, and History of Communism in the Global South. She is the Grantee of the Charles Wallace India Trust Fellowship (2022-23). She is also an Asian Graduate Student Fellow at National University of Singapore for 2022. Her article titled, “Mapping the Changing Notions Inequality Among the Trade Union Leaders of Colonial Bengal”, has recently been published in The Journal of Global Intellectual History, Taylor & Francis (ISSN:2380-1891).

Edited by Shuvatri Dasgupta

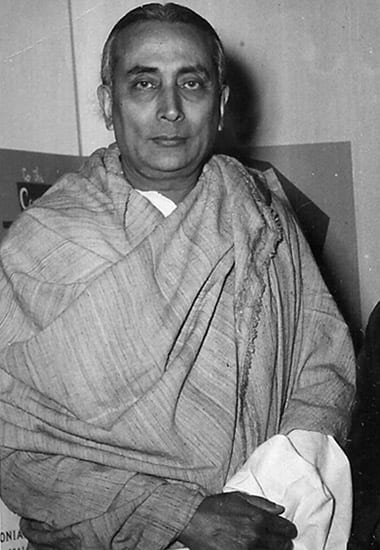

Featured Image: Saumyendranath Tagore, Courtesy of the Revolutionary Communist Party of India.