By Tamara Maatouk

Robert Rosenstone is Professor Emeritus of History at the California Institute of Technology. His previous publications include Crusade of the Left: The Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War (1969), Romantic Revolutionary (1975), Mirror in the Shrine: American Encounters with Japan (1988), Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to Our Idea of History (1995), History on Film/Film on History (2006, 2012, and 2018). He is the editor of Revisioning History: Film and the Construction of a New Past (1995), Experiments in Rethinking History (2004), and A Companion to the Historical Film (2012). Rosenstone is the founding editor of Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice.

Tamara Maatouuk is a contributing editor at the JHIBlog.

***

Tamara Maatouk: Your essay “History in Images/History in Words: Reflections on the Possibility of Really Putting History onto Film,” along with the responses it garnered from four established historians (David Herlihy, Hayden White, John E. O’Connor, and Robert Brent Toplin)—all published in the American Historical Review in 1988—placed the topic of history on film at the edge of the mainstream. However, on multiple occasions since then and in your book History on Film/Film on History, you have stated that for many professional historians, “film is suspect, something of a rival, an enemy,” and “to write extensively on film is to dare being marginalized within the profession” (xvii). Has this field made it into the mainstream or not? Does the history film still trouble and disturb historians, and more importantly, why?

Robert Rosenstone: Thank you for saying that my first comprehensive essay on the topic has put history film on the edge of the discourse. I think it has edged even a little farther into the field in the 35 years since then. However, most historians remain skeptical of both film as history and, at the same time, of the historical theorists of the last century. The insights of the latter point to the constructed and problematic nature of our written histories. Just a couple of months ago, I met a historian who, when I mentioned Hayden White, said, “Oh, you mean the guy who says you can make up anything you want about the past?” And yet, White’s body of work, as well as that of other theorists, has forcefully called into question the “truths” of traditional historical writing and has helped to open a theoretical way of taking history films seriously.

When I said, “to write extensively on film is to dare being marginalized within the profession,” I was talking directly to people like you, younger scholars who may not yet be fully acculturated into the dogmas and practices of the profession. The topic of film may still be on the margins, but now a bit less so. The rock band Buffalo Springfield has a wonderful line in one of their songs: “you step out of line, the man come and take you away.” Here the man means the police, and our field has its own cops. You are not considered a serious historian when you write about film as history. My evidence for this is largely anecdotal, based upon the remarks of younger scholars who can see the limitations of the written word in writing history. My question is, why? As White and other theorists have pointed out, the history we write is based on certain writing conventions that both enable and limit what we can say about the past. I wrote three more or less traditional narrative histories, and by the third one, I was saying to myself, “this is not precisely what happened. This is what I, after years of research, have decided what happened and why.” In the book Mirror in the Shrine: American Encounters with Meiji Japan, which embraces some of the literary techniques of the contemporary novel, I, to some extent, play with narrative to escape the confines of some traditions in academic history, which can be rigid, unforgiving, and dull for most potential readers, even historians. I think the rigidity of academic fields, which do not change very quickly, continues to make it difficult for the topic of film as history to enter the mainstream.

For many historians, film remains suspect because, and this is what we would have said in the sixties, that is where the action is—that is where people learn history for the most part—and thus, it is a genre over which historians have no control. Ignoring film, however, is just putting on blinders. Historians are in danger—perhaps we are already there?—of becoming a priestly caste. We talk to and write for each other and make rules about the world for each other, but we do not see whether we have an audience. I am not saying that everything should be popularized, or that traditional books should not be read. Of course, they are the heart of our historical knowledge. But I believe film to be another powerful medium, and it is folly not to come to grips with it.

TM: One of the responses that your 1988 essay triggered is Hayden White’s “Historiography and Historiophoty,” the latter is a term he coined and defined as “the representation of history and our thought about it in visual images and filmic discourse.” Part of your work since then, particularly your book History on Film/Film on History, is devoted to the exploration of “historiophoty,” or what historian Marc Ferro once suggested, “a filmic writing of the past.” As such, your approach to the topic of film as history has differed from other scholars who, as you put it, “write as if history films are not really about the past, but about the present” (xv). Can you tell us more about your approach, and how is that also different from similar approaches such as those of professors Pierre Sorlin and Nathalie Zemon Davis?

RR: I like the term “historiophoty,” and find it useful. I think, in a way, in History on Film/Film on History, I am responding to that term. In fact, Hayden and I became friends after his response to my AHR essay in which he coined the term. My work has changed enormously from my initial essays; it took me about 25 years to say, “why are we holding up all these barriers to a medium that is so important?” Ferro’s work, particularly the phrase “a filmic writing of the past,” was influential in this respect. I agree that is where I think my approach to history and film has differed from other scholars. These days, it seems that far more scholars in film studies than in history are working in the field of history and film, most prominent of whom is Robert Burgoyne. I roughly estimate that they seem to publish at least 75 percent of the articles, if not more, and their large questions are different from my own. They raise such questions as: Why was this film made? What does a film say about the time in which it was made? What socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural influences made it this way? In short, most film studies scholars try to understand history films as products of a particular present, as documents that tell us about the society in which they were produced and viewed. Their work is essential and their studies are often excellent, but they rarely deal with the historical contents portrayed in those films, or what they (may) add to our knowledge of the event, character, or era on which they focus. My approach has tried to shift the focus to how we, historians or non-historians, can think about these history films as contributions to our historical understanding and knowledge of the past as well as an alternative or simply a different way of retelling and reconstructing the past.

Nathalie Zemon Davis, who is also a good friend, has a somewhat similar approach to mine, but she draws back to the edge and is not quite willing to say that history film is a legitimate way of doing history. I do not know why she has pulled back, and I wonder if she still feels that way. Pierre Sorlin takes pretty much the same approach as those in Film Studies. Along the way, he makes the excellent point that “films must be judged not against our knowledge or interpretations of a topic but with regard to historical understanding at the time they were made” (21). My approach has been different, for I argue that the history film provides another discourse, a visual and oral discourse about the past, and that we historians (traditional gatekeepers of the past) have to learn how to read these visual works on their own terms and not naively by observing things like how the clothing or furniture is wrong for that period. The image, you know, cannot generalize the way a word can. You cannot show an invasion of one country by another or a revolution on the screen except by showing, for example, a small group of, say, soldiers who are doing the invading or are revolting. I am not trying to exclude the immense contributions of traditional history, but now we need to develop a clear set of guidelines that everybody can use to evaluate these visual histories. My work is an attempt to move towards such guidelines.

TM: One of the things that stood out to me in your earlier work is the way you address invention. Invention, as you argue, has been the most controversial issue when dealing with history film, for “the camera’s need to fill out the specifics of a particular historical scene, or to create a coherent (and moving) visual sequence, will always ensure large doses of invention.” You treat invention differently than how other historians would treat it; they use it more in terms of how accurate a scene is or how faithful it is to written accounts. However, you distinguish between two different kinds of invention: false invention and true invention. In other words, for you, invention is not simply about a fabricated character, event, or detail such as clothing or furniture, but about knowing the discourse of history on a particular event and ignoring it or not incorporating it in a film. Could you clarify this to our readers?

RR: I have pretty much given up the idea of true and false invention. That was an early idea, and my ideas have changed several times as I did more research over the years. I now think that the way to judge films is by how they interact with the discourse of history, with all the available knowledge on a topic and what has been published on it over the years, decades, or centuries. This is, after all, what we do with every new history book as well. You have hit the most challenging point when dealing with history on film, but I think invention is necessary for history films. They cannot do what written words do, so they do something else. “You may see the contribution of such works in terms not of the specific details they present but, rather, in the overall sense of the past they convey, the rich images and visual metaphors they provide to us for thinking historically. You may also see the history film as part of a separate realm of representation and discourse, one not meant to provide literal truths about the past (as if our written history can [ACTUALLY] provide literal truths) but metaphoric truths which work, to a large degree, as a kind of commentary on, and challenge to, traditional historical discourse” (7). In a history film, you must judge the totality of a work, and, in some ways, the details are less significant than the overall meaning. A film is essentially a dramatic work, which means it must invent some details; it is a time-limited medium, as books are not. Thus, we need different ideas of what works and what does not in this medium.

I provide many examples of how somewhat fictionalized history films can make strong historical arguments in my books. Let me mention three examples: Oliver Stone’s wholly fictional film, Born on the Fourth of July (1989), manages to convey the social upheaval of the Vietnam war era so vividly that, at certain points, I felt I was reliving my own experience of that sixties. Most of the characters in Glory (1989), focused on the 54th Massachusetts regiment in the Civil War, are fictional, as are many incidents, yet the film gives a visceral portrait of Black soldiers, the racism they suffered in the Union army, and their contributions to the Northern victory during the Civil War. The Return of Martin Guerre (1982) is a French film based on a famous and possibly true traditional tale of a man who left his village for years and either he or an imposter returns years later to his wife and children, though it is never clear if this is the same man or not. Even Natalie Davis, who wrote a book on the topic, cannot decide on this. Yet the film provides a fascinating portrait of power in a 16th-century French village.

TM: You employ the phrase “history film,” which you coined in History on Film/Film on History in opposition to the “historical film.” Can you explicate this term for our readers?

RR: For me and for the dictionary, the distinction is this: “historical” refers to anything from the past, while “history” refers to the study of the past. By using “historical film,” we are denigrating what I think is the contribution of the history film, “a film which evokes and makes meaningful the world of the past” (xii) and “engages the kind of questions which professional historians pose” (xviii), to our understanding of history. I have seen very few scholars using the phrase “history film,” for “historical film” is deeply implanted in our consciousness and has been used in the academy and by the public for a century, almost as soon as such films began to be made. That is why I have gotten to almost nowhere with my attempt to shift the reference. But I still believe that “history film” may grant the topic of film as history some academic seriousness that “historical film” has so far failed to do.

TM: Why is it important for historians to take history film seriously?

RR: Even though some historians take films seriously, they are a tiny minority of the profession, mostly, I believe, younger scholars like you. History films can offer interpretations of the past, which are certainly as interesting, and sometimes more so, than history on the page. To give an example: Hidden Figures (2016), a film about the crucial contributions of Black female mathematicians to the space program, keeps the focus on just three characters, making it much more interesting and pointed in its argument about discrimination than the book on which it is based. The latter introduces so many historical characters, whose stories dilute rather than enhance the meaning, making the narrative diffuse, confusing, and ultimately redundant.

Think of it this way: Why should the world of the past be brought to you solely by words when we have this splendid new medium for telling the past? Of course, the past on the screen and with sound is and must be enormously different from the past created in words by scholars, but it is time for historians to explore what such films add to our understanding of the past and to what extent they engage in a dialogue with written history, as some of them do. The time is surely past due for historians to take dramatic and documentary films seriously, in part, because that is where most people learn about the past, but even more because the visual media has become a giant that overwhelms us daily. Today, it is clearly the chief conveyor of public history in our culture. Who reads the overwhelming majority of history books other than historians? A sale of a few thousand copies of a work of history is considered a raging success, and the average work may never reach a thousand. This is a sad commentary in a population of more than 330 million people. Yet an audience of many millions is common for a history film.

TM: One of the main contributions of your book is that it experiments with a methodology to read history films, which you refer to as “the history film’s rules of engagement with the past.” Such a methodology cannot be but interdisciplinary, as you borrow from history and film studies and invite us to significantly change the way we think of history. What are some of these rules of engagement and the assumptions about history behind them?

In 1988, AHR editor David Ransel asked me to create a once-a-year history film review section for the journal. I edited it for six years, then turned the job over to Tom Prasch, who was doing a splendid job until the subsequent editor of the AHR canceled it on the grounds that historians did not know how to review films. This was not true of our actual reviewers, who tended to know quite a bit about film. But what we must ask is, why such a judgment? Might it not be crucial for historians to learn how to analyze the history films that shape many viewers’ sense of the past?

The first basic rule of engagement is that you have to take film on its own terms, to study it according to new standards. You cannot judge it by the same terms we judge oral history, written history, or social science history. Other people might come along and find other rules of engagement, but one must respect the medium and know its boundaries, limitations, and capabilities. Film can specify things in a way that a book cannot do and vice versa—it adds color, sound, movement, and dialogue to the past it constructs; it stretches, squeezes, slows down, and fast forwards time—and so it must be judged differently. The person who has done the most detailed study of this is Eleftheria Thanouli, the author of History on Film: A Tale of Two Disciplines.

And, of course, any such study must be interdisciplinary. I had to do a lot of reading in film theory and the theory of history, which brings us to the second basic rule of engagement: we must change how we think about history. What we know now from the great theorists of the last half century is that written history is not the same practice I was taught in graduate school in the sixties. Many historians I know and read seem to feel the same way, but this recognition has hardly changed how people write or do history. They do not teach you how to write in graduate schools. When you enter graduate school, there is an assumption that you know how to write, and then you have seminars where people only criticize the content of your work, as if the writing itself was a neutral medium. But we know that writing is not neutral; we know that there is an infinite amount of data on almost every topic, from which you pull out the bits and pieces that make sense to the thrust and aim of your work, which starts with the very choosing of a topic; and we know that your values, beliefs, and experiences underlie the choice of a topic, how you conduct research, formulate explanations, and construct your narrative or analysis. However, we still do not recognize enough that our academic historical writing is not the sole truth about our topic but only an attempt to make sense of some aspects of the vanished world of the past.

Tamara Maatouk is a Ph.D. candidate in Middle Eastern history at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. She holds a B.A. in Cinema and Television from USEK and an M.A. in History from the American University of Beirut. Her research explores the lived experiences and expectations of Egyptians during the 1960s through the lens of cinema. She is the author of Understanding the Public Sector in Egyptian Cinema: A State Venture, Cairo Papers in Social Science 35:3 (Cairo; New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2019).

Edited by Tom Furse

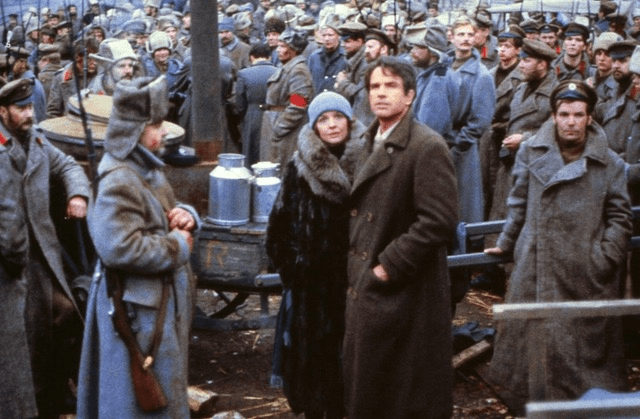

Featured Image: Diane Keaton as Louise Bryant and Warren Beauty as Jack Reed in Reds (1981). © Paramount Pictures