By Andrew W. Wiley

Civil War era historians have illuminated how crucial concepts of loyalty, duty, and treason were to nineteenth-century Americans. During the war, those who embraced unionism employed rhetoric around each to attack Confederate sympathizers and others they viewed as disloyal to the country. My research furthers this scholarship by looking at John C. Frémont’s 1864 challenge for the presidency in the Midwest. Abraham Lincoln’s supporters took Frémont’s challenge seriously. They feared the former general might wrest the Republican Party’s presidential nomination or make an independent run for the White House. Even if unsuccessful, a challenge for a presidential nomination could damage the incumbent. In response, Lincoln’s political allies turned the rhetoric of treason and loyalty they had honed against Confederate sympathizers on Frémont. Their efforts helped block a threat to the president at a crucial time in his campaign for a second term.

While some historians have downplayed the seriousness of antiwar activity in the Civil War North because of the lack of overt support for the Confederacy, Jennifer L. Weber and others have broadened our understanding of what constituted opposition to the war. Helping the Confederacy was only one facet of antiwar opposition in the North. Opposition could take the form of draft dodging, printing antiwar newspapers, backing certain political candidates, promoting a peaceful settlement, and encouraging soldiers to desert. Robert M. Sandow has also reminded us that antiwar northerners resided throughout the free states, including in places far removed from the battlefields. Recently, Julie A. Mujic has noted how the rhetoric of loyalty to the Union even filtered into courtship rituals between young couples. Northerners debated these questions of duty, loyalty, and treason until the war ended in 1865.

As noted above, Republicans and Democrats who supported the war effort developed and employed rhetoric around concepts of loyalty and treason to attack those they considered disloyal, including Lincoln’s political rivals. Though the sixteenth president faced several political competitors leading up to the 1864 presidential election, I will focus on Frémont’s rival campaign for the Republican or Union Party’s nomination in the Midwest. The erstwhile general found much support in the region due to his popularity with German abolitionists and former revolutionaries: his 1861 emancipation while commanding U.S. soldiers in Missouri had cemented him as a dedicated abolitionist in their eyes. In the contest, Frémont pitched himself as a radical challenger to the more moderate Lincoln who had delayed moving against slavery and proposed lenient reconstruction policies (he had rescinded Frémont’s 1861 order). Believing the former general was a threat to Lincoln’s nomination, those who backed the president turned their well-developed language of treason against Frémont and his supporters.

Lincoln had reason to fear a political challenger. By early spring 1864, the president and the country faced numerous challenges. Civilians were dissatisfied with the draft which excluded the wealthier members of society, the Lincoln administration had suspended habeas corpus and shut down some opposition newspapers, and worst of all for those hoping for a quick end to the war, the two main U.S. armies were stalled in front of Richmond and Atlanta. The war’s sour turn had alienated much of the northern public as casualties mounted. With many moderates and plenty of radicals dissatisfied with Lincoln’s performance, the environment seemed ripe for a political challenger to rise against the first Republican president. While there were many possibilities, one potential rival stood out due to his support from radicals and his willingness to challenge Lincoln—Frémont.

In 1864 one group of determined and disaffected Republicans called for a convention the following May to discuss the incumbent president’s chances in the upcoming election and possibly nominate an alternative. The convention assembled in Cleveland, Ohio, where attendees railed against the administration for delaying emancipation. As a more radical alternative to Lincoln, the convention nominated Frémont for president (Weekly Wabash Express, Terre Haute, IN, June 1, 1864). Making his opposition to Lincoln clear, the former general accepted the nomination via letter a few days later (Greencastle Banner, IN, June 23, 1864). The feared split in the Republican Party seemed a foregone conclusion with radicals supporting Frémont as their candidate. As Democrats gloated over the events in Cleveland, Lincoln supporters prepared for a pitched battle against Frémont and his run for the presidency in the court of public opinion.

For many Republicans, calling Frémont men traitors was not a giant leap: many Republicans already equated a potential Lincoln defeat in 1864 with a victory for the Confederacy (Macomb Journal, IL, April 15, 1864). Shortly after the convention broke, administration loyalists in the Midwest labeled the Frémont delegates copperheads, the same name they called opponents of the war. Even before he received news of Frémont’s acceptance of the nomination, one Republican commenter called the meeting a “copperhead convention” (Grand Traverse Herald, Traverse City, MI, June 10, 1864). While downplaying the convention, a Wisconsin Republican blamed copperheads for the meeting, predicting Democrats would use the Frémont nomination in the fall canvass to boost their own nominee (Dodgeville Chronicle, Dodgeville, WI, June 9, 1864). For these supporters of the administration, Frémont men had earned the treason label. In their view, a defeat for Lincoln might mean a defeat for the Union.

Some of the loudest cheers against Frémont came when his name was barely mentioned at all. Republicans and War Democrats met in Baltimore, Maryland, on June 7th for their national convention. At the meeting, sticking with the theme of unity, few brought up the Cleveland convention or the former general himself. A fleeting reference came from Tennessee firebrand Parson G. Brownlow who, drawing similarities between peace Democrats and the Frémont men, assured the convention of the Tennessee delegation’s loyalty. He insisted they could never have attended either the Democratic convention in Chicago, Illinois, that had nominated George B. McClellan, or the Cleveland convention that had nominated Frémont. Brownlow’s comment drew thunderous applause from the delegates. When attendees voted for a presidential nominee, Lincoln won an overwhelming victory. Despite their success at the convention, Lincoln supporters stepped up their campaign against Frémont after delegates returned home.

With a nomination, Lincoln supporters intensified their attacks on the Frémont men. Hoping to motivate their hesitant brethren to vote for Lincoln, they assured the potential defectors that staying home or voting for Frémont meant a vote for McClellan (Marshall County Republican, Plymouth, IN, July 14, 1864; Weekly Wabash Express, Terre Haute, IN, August 3, 1864). An Ohio Republican repeated the charge, saying Frémont men were doing the work of butternuts and draft dodgers, opponents who had weakened the war effort (Hancock Jeffersonian, Findlay, OH, August 19, 1864). Illinois Republicans joined in. A reporter for the Chicago Tribune comically noted a failed effort to form a Frémont club in southwestern Illinois.Calling Union County “one of the worst copperhead counties” in the state. The reporter labeled the Frémont backers Confederate sympathizers, and noted the meeting broke up in disgust at not finding enough members in the county to even form a small club (Sangamo Journal, Sangamon, IL, July 14, 1864).

Frémont’s campaign prompted many Lincoln supporters to chide any opposition to the president. Those who publicly endorsed the president were called out for aiding and abetting the enemy if they wavered in any degree. In August, Ohio Senator Benjamin Wade and Maryland Congressman Henry Winter Davis, both Republicans, published a critical message about Lincoln and his pocket veto of a congressional reconstruction bill (New York Tribune, August 5, 1864). Indiana Republican John D. Defrees wrote to Wade urging him to be more circumspect in his criticism, arguing if Lincoln lost it meant a “restoration of the slave power.” Although Lincoln faced many conservative critics, Defrees was far more concerned with those who had pushed for emancipation earlier in the war. The Republican noted that most of Lincoln’s critics in 1864 were among those “Union men” who had celebrated the Emancipation Proclamation two years earlier. Defrees’s rhetoric against Frémont’s supporters matched the words he had lobbed at Confederate sympathizers (John D. Defrees to Benjamin Wade, August 7, 1864, The Papers of Abraham Lincoln, Library of Congress).

Despite his early prospects, the general’s support weakened late in the summer as U.S. armies made progress on the battlefield. Hoping to gin up one last show of support, some backers assembled in August at the local Masonic Hall in Indianapolis, where they endorsed the resolutions adopted in Cleveland and criticized the administration. Delegates railed against the arrests of civilians in the border states, the closing of newspaper offices by the U.S. army, and the continued war. Unsurprisingly, they endorsed Frémont in the convention’s waning hours. Despite the enthusiasm of the Frémont men, the meeting drew little Republican attention outside those discontented with the Lincoln administration. Recognizing that he did not have a realistic chance at the nomination, Frémont himself ended his candidacy in September and endorsed Lincoln rather than see McClellan win (Daily State Sentinel, Indianapolis, IN, August 26, September 23, 1864). Without another candidate siphoning votes, the president cruised to a second term, easily defeating the Democratic nominee McClellan in the general election.

Frémont’s failed 1864 bid for the Republican or Union Party’s presidential nomination provoked a strong response from northerners loyal to Lincoln and his administration. Believing Frémont’s run for the presidency was a direct threat to Lincoln, midwestern Republicans and War Democrats turned their rhetoric of treason and disloyalty on Frémont and his ardent supporters. Using the same language they had employed against Confederate sympathizers, the administration’s supporters labeled some of its former allies copperheads and enemies. Once Frémont renounced the Cleveland convention’s nomination in September 1864, the attacks ended; most Republicans and War Democrats welcomed their former brethren back into the fold. Despite the reunification, their efforts showed just how far the Lincoln men would go to defend the president, his administration, and the Union, turning their rhetorical barbs of treason against their sometime allies.

Andrew W. Wiley (PhD University of Calgary) is the editor of the Papers of Martin Van Buren and an Assistant Professor of History at Cumberland University, in Lebanon, Tennessee. His dissertation focused on how a fusion of economic liberalism and racism that emerged in the Civil War Era Midwest became crucial elements of American conservatism. He is currently revising his dissertation and will submit it to a university press by the end of Summer 2023.

Edited by Zach Bates

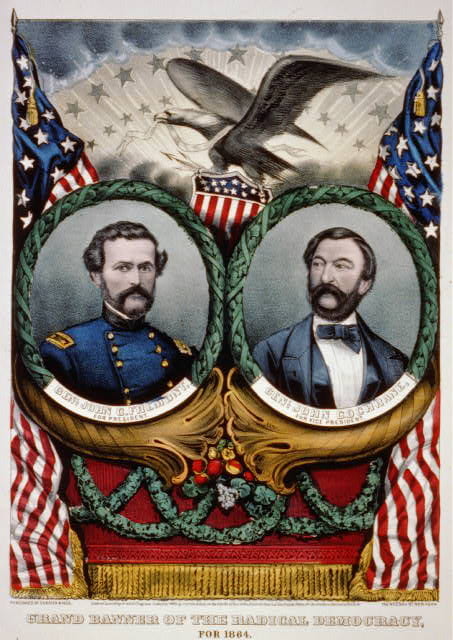

Featured Image: Grand banner of the radical democracy, for 1864. Courtesy of The Library of Congress.

1 Pingback