by guest contributor John Pollack

‘Tis the season. Not that season—but rather, the curious period in the United States between the holidays of “Columbus Day” and “Thanksgiving” when, at least on occasion, the issues confronting America’s Native peoples receive a measure of public attention. Among this year’s brutal political battles has been the standoff at Standing Rock Reservation, where indigenous and non-indigenous peoples from the entire continent have gathered to support the Standing Rock Sioux’s opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline, the construction of which would threaten sacred lands. Although this conflict will not be a subject of discussion at every Thanksgiving table, at the very least the resistance at Standing Rock serves as a reminder of the very real environmental and political battles that continue to play out in “Indian Country.”

Standing Rock Protestors. Image courtesy of The Lakota People’s Law Project.

On October 13, 2016, I attended a lecture given by Winona LaDuke to open the conference “Translating Across Time and Space,” organized by the American Philosophical Society and co-sponsored by the Penn Humanities Forum. I was in an auditorium at the University Museum at the University of Pennsylvania, but Ms. LaDuke did not attend the conference in person. She spoke instead from an office at Standing Rock, where she is leading resistance to the pipeline. Ms. LaDuke’s remarks at a conference focused upon the study and revival of endangered Native languages were a reminder to me and other audience members that being a “Native American Intellectual” means being a political figure, a public voice speaking and writing in contexts of imperial expansion and ongoing legal, military, and economic conflicts over territory. We may date the creation of the term “intellectual” to the late 1890s, with Emile Zola’s public attack upon the French military for covering up the innocence of Alfred Dreyfus—but it is arguably the case that Native American public leaders, whatever labels we assign them, have been speaking truth to power since 1492.

Over the past year, a team at Amherst College, in conjunction with the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums; the Mukurtu project; and the Digital Public Library of America, has been planning a framework for a “Digital Atlas of Native American Intellectual Traditions.” This exciting initiative promises to develop a new set of lenses through which we may observe and connect the intellectual histories of America’s indigenous peoples, across time and across territories. All students of the “history of ideas” should welcome this extension of the boundaries of the field in new directions.

From Collection(s) to Project

Collectors of books and documents can play surprising roles in shifting scholarly attention in new directions, and this project is a case in point. In 2013, Amherst College Library’s Archives and Special Collections acquired the Pablo Eisenberg Native American Literature Collection. Known now as the The Younghee Kim-Wait (AC 1982) Pablo Eisenberg Native American Literature Collection, after its collector and the donor whose gift enabled the purchase, the collection, Amherst suggests, is “one of the most comprehensive collections of books by Native American authors ever assembled by a private collector.” (I would add that this is really a collection of mainly Native North American authors.) Few of the titles in the Eisenberg Collection are unknown or unique exemplars—but their assembly by one collector into one collection motivated Mike Kelly, Kelcy Shepherd, and their Amherst colleagues to investigate how such a collection might help reshape discourses about Native Americans and their intellectual histories.

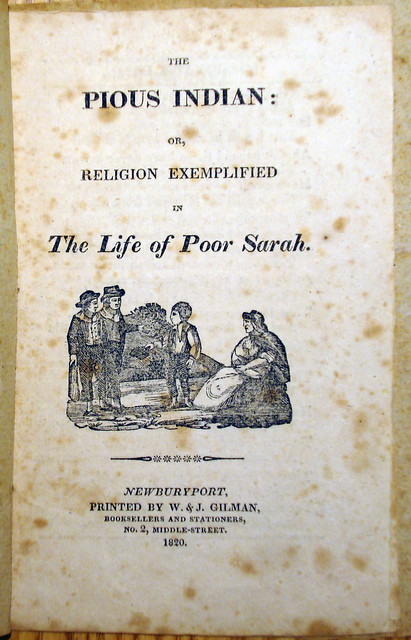

Click to view Amherst’s Flickr gallery of images from the Kim-Wait/Eisenberg Native American Literature Collection.

Working outward from this impressive body of material, their project will create a framework drawing together “Native-authored” materials held in widely scattered repositories. They seek a digital solution to one of the problems researchers working in digital environments regularly confront: the difficulty of connecting related items across institutions. The authors note:

Search and retrieval of individual items allows for only limited connections between related materials, erasing relevant context. Tools for visualizing and representing these networks can ultimately provide even greater access and understanding, challenging dominant interpretations that misrepresent Native American history and obscure or de-emphasize Native American intellectual traditions.

Digital projects, I would add, can often exacerbate rather than reduce this effect of disaggregation and de-contextualization. Working online, we can easily fail to comprehend a collection of documents or printed materials as a collection, in which the meaning of individual items may be shaped by the collection as a larger whole. Some online projects select out particular items, extracting and featuring them—much as an old-style museum might present an artifact in a display with a rudimentary label, disconnected from its cultural origins. Others provide digital results in an undifferentiated mass. The immediate benefit of finding new materials online can feel impressive, but the tools for interpreting what we access can feel strangely limited.

The Digital Atlas, the authors argue, will fill a void, the current “absence of a national digital network for Native-authored library and archival collections.” Here they invoke that recurring librarians’ dream—the search for the perfect search tool. This can take the form of “union” catalogs that gather information from many places into one data source and make them easily searchable; or of “federated” searching, the creation of tools that straddle multiple data platforms and present results for researchers in a single, coherent view; or of the “portal,” an organized launching point that gathers disparate research materials together. Still to be negotiated, I imagine, is how this “national digital platform” will connect with other such “national” platforms, including the Digital Public Library of America.

Searching protocols represent only one of the challenges; the work of classification itself must be subjected to scrutiny. One of the project’s partners is Mukurtu, an open source Content Management System (CMS) that has been designed to encourage the cooperative description of indigenous cultural materials using categories designed by Native peoples themselves. Mukurtu, which describes itself as “an open source community archive platform,” provides tools allowing repositories to rethink the ways in which materials by or about Native peoples are categorized, cataloged, and accessed.

This new methodology will make “Native knowledge” more visible in collections held by libraries, archives, and museums:

The project will develop methods for incorporating Native knowledge, greatly enriching public understanding of Native culture and history. It will identify approaches for enhancing metadata standards and vocabularies that currently exclude or marginalize Native names and concepts. We will share this work with the digital library community and with Native librarians, archivists, and museum curators.

The project will “include both tribal and non-Native collecting institutions, building relationships between the two.” This promise to create new partnerships between academic and institutional collections and Native communities is a welcome vision of sharing and exchange. A number of institutions are redefining what the “stewardship” of Native documents or artifacts means and reconsidering the thorny question of who “owns” the cultural productions of Native peoples. At the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, for example, the Center for Native American and Indigenous Research has embraced a community-based methodology that actively shares indigenous linguistic collections with Native peoples and invites Native researchers to take intellectual if not physical ownership of these collections, wherever they reside.

This proposal’s creators have, for now, chosen to avoid a discussion of what is, and what is not, “Native-authored.” Authorship and authority are always contested domains, and Native authorship has been a subject of debate since the eighteenth century. Like African American writers, Natives have had to work with or against non-Native editors, printers, publishers, and of course readers. I hope that the Digital Atlas will give us new tools for studying these tensions and new ways to chart the impacts of Native author-intellectuals over time, in printed books, in periodicals and newspapers, at public events, and in letters.

Mapping an “atlas”

Another argument behind the Digital Atlas is that Native writing must be understood in its relationship to place: to location, to land, to social memory, and to the environment. At the same time, the authors insist that we cannot adopt a static spatial view but instead must focus on mobility—that is, on the connections between authors, texts, and routes.

The proposal poses this question: “What tools, methodologies, and data would be required to visualize and represent the networks through which Native people and authors traveled and maintained/produced Native space?” Data “visualization,” the use of mapping software to show nodes of activity and networked connections, has become a standard tool in the field of digital humanities and a frequent complement to scholarship in fields including book history, medieval and renaissance studies, and American literary studies. Indeed, Martin Brückner has recently argued that literary studies is in the midst of a widespread “cartographic turn,” noting the pervasive language of cartography—the map as tool and the map as metaphor—throughout the field.

Given the project’s focus upon geography, visualization, and mobility, though, I confess that I find the Atlas’s emphasis that it will be a “national” product disappointing, if understandable—with its suggestion of a continuing focus upon the old familiar geography of the nation-state. I suspect that the project’s authors are well aware of this tension. Scholars like Lisa Brooks (an advisor to the Digital Atlas) and others have pushed us to think about the many routes along which Natives and their words have circulated: through territories shaped by geographic features and personal connections; along riverine networks; and over trading and migration paths that long antedate and overlap the national, state, or territorial borderlines drawn by European surveyors and colonial agents. Will the Atlas help us follow the movements of ideas along non-national paths and across networks other than those circumscribed by nations? I hope so.

Intellectual traditions, Intellectual histories

With its focus on assembling and mapping intellectual traditions, the Atlas proposal also makes the implicit argument that it is time to move beyond the old debate about the influence of the “oral tradition” and the impact of “written culture” upon Native peoples.

As Brooks and others have persuasively argued, anthropologists in the nineteenth and early to mid twentieth centuries often ignored the ways in which Native peoples used various forms of writing, including European ones, for their own purposes (cultural, literary, and legal), preferring instead to search for presumably older oral traditions that were somehow isolated from and uncontaminated by writing. Historians of Native America now question the dichotomy between oral and written. We must be particularly cautious about identifying the former as essentially Native and the latter as essentially Western or European.

In the European context too, the dichotomy has been questioned. Scholars including Roger Chartier and Fernando Bouza have pointed out the permeability of oral and written discourses within the European context and shown that these categories were both unstable and contested in the early modern period. Texts and images circulated through the social orders in complex ways, and oral, written, and visual forms maintained overlapping kinds of authority.

To be sure, European colonists, missionaries, and political leaders sought to create colonial regimes in which the written and the printed word would be dominant, even as orality continued to occupy an important place within their own cultures. Yet Native peoples in many regions, from Peru, to Mexico, to Northeastern North America often successfully retained their own highly developed cultures of oratory. And rather than classifying indigenous populations as peoples “without writing,” we have come to understand that the definitions of communication must be broadened to include the range of semiotic systems Native peoples used to share and exchange goods and information, and to preserve narratives and historical memory. Native peoples also adopted, adapted to, appropriated, or resisted European writing and print culture in a wide variety of ways.

But why, I wonder, will this be an atlas of intellectual traditions and not of intellectual histories? With this title, the project softens its potential impact upon the field known as intellectual history or the history of ideas. It seems to locate the project in an anthropological and not a historical mode. Native peoples, like peasants, workers, lower class women and other so-called “peoples without history” (to borrow Eric Wolf’s ironically charged phrase), are still too often relegated to the realm of tradition, and locked into a static past.

In 2003, Robert Warrior pointed out that the field of American Studies had only just begun to include the voices of Native American Studies scholars. We might now extend his point to encompass the field of the “history of ideas” or intellectual history. A search across the content of the Journal of the History of Ideas turns up not a single reference to Warrior or his work, and I am hard pressed to find a discussion in its pages of the “history of ideas” in Indian Country. Rather than assuming that the field’s concepts are too Euro-centric and have no bearing upon an equally complex but distinctly different realm of Native ideas and philosophies, I would prefer to work toward more common ground. We can expand the history of ideas to encompass Native American intellectual histories—while respecting Warrior’s call to maintain the “intellectual sovereignty” of Native America (Secrets 124).

I eagerly await the results of the Digital Atlas of Native American Intellectual Traditions. I look forward to studying its reimagined maps of American intellectual history, and to hearing more voices of the public intellectuals of Native America, past and present.

John H. Pollack is Library Specialist for Public Services at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania. He holds a Ph.D. in English from Penn; he has published on colonial writings from New France and edited a volume of essays on Benjamin Franklin and colonial education. He is currently working on a monograph about the circulation of Native words in early European texts on the Americas.

November 23, 2016 at 12:44 pm

Reblogged this on O LADO ESCURO DA LUA.