by guest contributor Matthias Pfaller

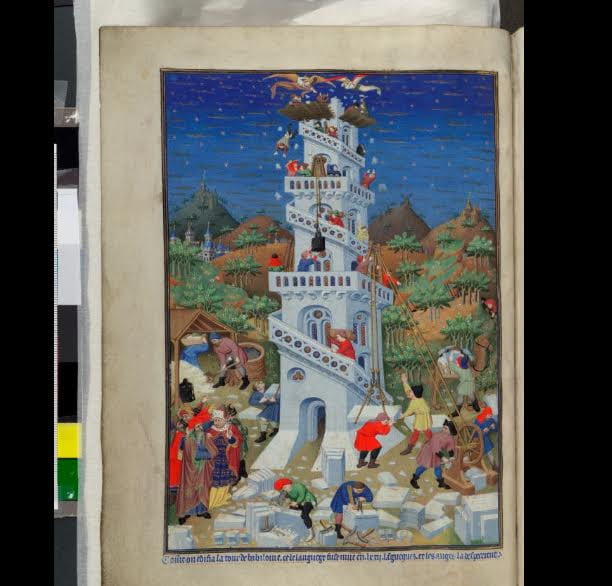

The Tower of Babel, one of the images made for Henry VI. BL Add MS 18850, f. 17v (photo courtesy British Library)

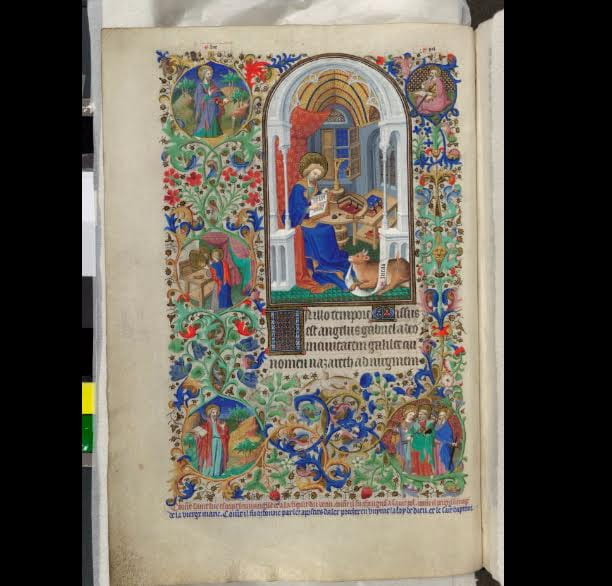

The Bedford Book of Hours, illustrated by the most capable artists of Paris of the fifteenth century, is one of the most splendid of late-medieval illuminated manuscripts, and one of the most famous pieces in the British Library’s present collection. Commissioned some time between 1410 and 1415, in the midst of the Hundred Years’ War, it was intended for the French dauphin; this, at least, is what scholars guess from its lavish production. However, in 1423, the book switched sides: it was bought by the Duke of Bedford, the brother of English King Henry V, who married that same year. The newlyweds customized the almost-finished book, and had their portraits and emblems added on several folios.

In 1430, the book again received a new owner, the Bedfords’ nephew King Henry VI of England, who had just become old enough to be crowned king of France under the provisions of the Treaty of Troyes. Accordingly, the book of hours was adapted to the needs of the boy king and got new miniatures, emblems, and, curiously, two lines of descriptive text underneath the border decoration on almost every folio.

These captions have been passed over in almost every article and monograph on the Bedford Book of Hours. Scholars made attempts to date them and roughly reflected on their purpose, but left it at that. The real problem for me, however, is not the scarce material, but the description and proper classification of this feature. They do not belong to any established text genre like prayers, bible excerpts, or standardized exegesis. Nor are captions generally an inherent part of genres such as books of hours, apocalypses, moralized bibles, and psalters. There is a standardized categorization known as “extra-textual content,” where we find all kinds of text too idiosyncratic to be subsumed under general terms, like speech in banderoles, occasional subtitles, and scribbles. But as the basis of a detailed analysis of the captions, this seems not at all satisfying in accuracy and meaningfulness.

Since these captions—an elaborate program on almost 300 folios in a royal commission—can hardly be a side-product of some other decoration, the idea was to look for predecessors. Indeed, a descriptive one to three lines beside miniatures is actually quite a common feature in a range of books from the twelfth to the fifteenth century across Europe. Yet no classification in manuscript studies considers this element, which makes every description specific to the object in question, without the possibility of grouping the findings under common traits.

The usual detour in such instances is to connect the objects in question through a demonstrable influence, still keeping the texts separate. In this case, a corpus of English manuscripts from the thirteenth and fourteenth century with captions suggests an English tradition of descriptive subtitles. A group of apocalypses (Bodleian Oxford MS Auct. D. 4.17, Pierpont Morgan MS 524, Trinity Cambridge MS R. 16.2) dating from around 1255, as well as the Holkham Bible Picture Book from 1330 (BL Add MS 47682), and the Psalters of Peterborough (KBR MS 9961-62) and of Queen Mary (BL Royal 2 B VII) from around 1315, all feature captions in the same manner as in the Bedford Hours. The Psalters were made for the English royal family or came into their possession, which is why it is reasonable to assume later kings have known them. It is therefore possible that the Duke of Bedford may have chosen to have captions added in the French manuscript to remind the young king of his English roots (aside from the obvious descriptive factors of such text).

This theory ties together a small number of subtitled manuscripts, but does not solve the categorization problem of treating captions as random extra-textual content. Upon closer examination, the English manuscripts mentioned above — besides inhabiting traditional genres such as the apocalypse, bibles and psalters — all show links to the French genre of the moralized bible, which is itself a strict corpus of a few manuscripts from the thirteenth century onwards, created for the French royal family. When the first of these bibles came to the English court in 1250, it massively influenced local book production, so that the standard text of English apocalypses actually derives from the French moralized bible. In the Peterborough and Queen Mary psalters, too, the narrative of typological cycles was inspired by the French type. Most important, the pictorial program of the Bedford Book of Hours follows the same scheme. From there it is only a small step to suggest that the captions, added at least a decade after the painting of the miniatures, were intend to complete the moralized bible that the images had begun.

Seeing a moralized bible within a book of hours stretches the boundaries of classic genres in manuscript studies. Indeed, the format of the moralized bible in the Bedford Hours does not at all correspond to what a moralized bible usually looks like. However, the structure, content and purpose of both pictorial and caption program allow this association and, what is more, finally offer a possibility to describe captions of this particular sort as part of a genre which turns out to be more flexible than initially conceived. This allows features like captions to be integrated into our understanding of medieval book production, instead of being treated “extra-categorically.”

Matthias Pfaller received an MSc in Art History from Edinburgh University. From September, he will be a graduate intern at the Getty Museum.

Leave a Reply