by guest contributor Agnieszka Smelkowska

At first, Russian TV surprises and disappoints with its conventional appearance. A mixture of entertainment and news competes for viewers’ attention, logos flash across the screen, and pundits shuffle their notes, ready to pounce on any topic. However, the tightly controlled news cycle, the flattering coverage of President Vladimir Putin, and a steady indignation over Ukrainian politics serve as reminders that not all is well. Reporters without Borders, an international watchdog that annually ranks 180 states according to its freedom of press index, this year assigned Russia to a dismal 148th position. While a number of independent print and digital outlets persevere, television has been largely brought under state control. And precisely because of these circumstances, television programming tends to reflect priorities and concerns of the current administration. When an ankle sprain turned me into a reluctant consumer of state programming for nearly three weeks, I realized that despite various social and economic challenges, the Russian government remains preoccupied with the Soviet victory in WWII.

Celebrated on May 9th, Victory Day—or Den Pobedy (День Победы) as it is known in

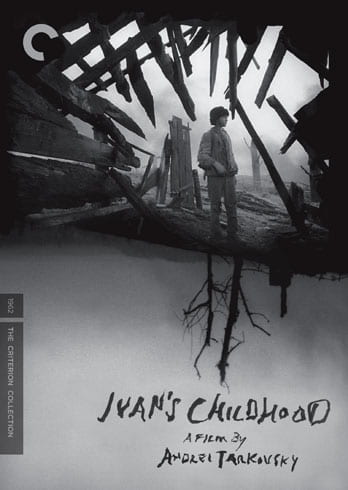

Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood (1962)—the child protagonist encounters the reality of war.

Russia—marks the official capitulation of Nazi Germany in 1945 and is traditionally celebrated with a military parade on the Red Square. During the few weeks preceding the holiday, parade rehearsals regularly shut down parts of Moscow while normal programming gives way to a tapestry of war-related films. The former adds another challenge to navigating the already traffic-heavy city; the latter, however, provides a welcome opportunity to experience some of the most distinguished works of Soviet cinematography. Soviet directors, many veterans themselves, resisted simplistic war narratives and instead focused on capturing human stories against the historical background of violence. Films like Mikhail Kalatozov’s Cranes are Flying (1957), Andrei Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood (1962) or Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) are widely recognized for their emotional depth, maturity and an uncompromising depiction of the consequences of war. Unfortunately, these Soviet classics share the silver screen with newer Russian productions in the form of Hollywood-style action flicks or heavy-handed propaganda pieces that barely graze the surface of the historical events they claim to depict.

The 2016 adaptation of the iconic Panfilovtsy story exemplifies the problematic handling of historical material. The movie is based on an article published in a war-time Soviet newspaper, which describes how a division of 28 soldiers under the command of Ivan Panfilov distinguished itself during the defense of Moscow in late 1941. The poorly armed soldiers who came from various Soviet Republics managed to disable eighteen German tanks but were all killed in the process. The 1948 investigation, prompted by an unexpected appearance by some of these allegedly dead heroes, exposed the story as a journalist exaggeration, designed to reassure and inspire the country with tales of bravery and an ultimate sacrifice. Classified, the report remained unknown until 2015 when Sergei Mironenko, at the time director of state archives, used its findings to push against the mythologization of Panfilov and his men, which he saw as a sign of increasing politicization of the past. His action provoked severe, public scolding from the Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky that eventually cost Mironenko his job, while Panfilov’s 28 (2016) was shown during this year’s Victory Day celebration.

Panfilov’s 28 (2016): Soviet heroism in modern Russian cinematography.

Many western commentators have already noted the significance of Victory Day, including Neil MacFarquhar, who believes that President Putin intentionally turned it into the “most important holiday of the year.” The scale of celebration seems commensurate with this rhetorical status and provides an impressive background for a presidential address. The most recent parade consisted of approximately ten thousand soldiers and over a hundred military vehicles—from the T-34, the venerable Soviet tank to the recently-developed Tor missile system, which can perform in arctic conditions. Predictably the Russian coverage differs from that presented in the western media. The stress does not fall on the parade or President Putin’s speech alone but extends to the subsequent march of veterans and their descendants, emphasizing the continuation between past and present. The broadcast of the celebration, which can be watched anywhere between the adjacent to Poland Kaliningrad Oblast and Cape Dezhnev only fifty miles east of Alaska, draws a connection between Russia’s current might and the Soviet victory in the war. Yet May 9th did not always hold its current status and only gradually became the cornerstone of modern Russian identity.

While in 1945 Joseph Stalin insisted on celebrating the victory with a parade on the Red Square, the holiday itself failed to take root in the Soviet calendar as the country strived for normalcy. The new leader Nikita Khrushchev discontinued some of the most punitive policies associated with Stalinism and promised his people peace, progress, and prosperity. The war receded into the background as the Soviet Union put a man into space while attempting to put every family into its own apartment. Only after twenty years was the Victory Day officially reinstated by Leonid Brezhnev and observed with a moment of silence on state TV. Brezhnev also approved the creation of a new Moscow memorial to Soviet soldiers killed in the war—a sign that Soviet history had taken a more

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Aleksandrovsky Sad, Moscow – Russia, 2013. (Photo credit: Ana Paula Hirama/flickr)

solemn turn. Known as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Могила Неизвестного Солдата), a bronze sculpture of a soldier’s helmet resting on a war banner with a hammer and sickle finial pointing towards the viewer symbolizes the massive casualties of the Soviet Union, many of whom were never identified. Keeping an exact list of the dead was not always feasible as the Red Army fought the Wehrmacht forces for four years before taking Berlin in April of 1945. Historians estimate that the Soviet Union lost approximately twenty million citizens—the largest absolute (if not proportional) human loss of any state involved in WWII. For this reason, in Russia and many former Soviet republics the 1941-1945 war is properly known as the Great Patriotic War (Великая Отечественная Война).

The victory over Nazi Germany, earned with a remarkable national sacrifice, was a shining moment in otherwise troubled Soviet history and a logical choice for the Russian Federation, a successor state of the Soviet Union, to anchor its post-ideological identity. Yet the current Russian government, which carefully manages the celebration, cannot claim credit for the popularity that the day enjoys among regular people. Many Russian veterans welcome an opportunity to remember the victory and their descendants come out on their own volition to celebrate their grandparents’ generation. This popular participation has underpinned the holiday since 1945. Before Brezhnev’s intervention, veterans would congregate informally and quietly to celebrate the victory and commemorate their fallen comrades. Today, as this war-time generation is leaving the historical stage, their children and grandchildren march across Moscow carrying portraits of their loved ones who fought in the war, forming what is known as the Immortal Regiment (Бессмертный полк). And the marches are increasingly spilling into other locations—both in Russia and worldwide. This year these processions took place in over fifty countries with a significant Russian diaspora, including Western Europe and North America.

The Immortal Regiment in London, 2017. (Photo credit: Gerry Popplestone/flickr)

This very personal, emotional dimension of the Victory Day has been often overlooked in western coverage, which reduces the event to a sinister political theater and a manifestation of military strength. The holiday is used to generate a new brand of modern Russian patriotism precisely because it already resonates with the Russian public. People march to uphold the memory of their relatives regardless of their feelings towards the current administration, views on the annexation of Crimea, or attitude towards NATO. Although this level of filial piety can be manipulated, my Russian friends seem to understand when the government tries to capitalize on these feelings. Mikhail, my Airbnb host, who belongs to the new Russian middle class, and who few years ago carried a portrait of his grandfather during the Victory Day celebration, remarked that the government attached itself like a “parasite” to the Immortal Regiment phenomenon because of its popularity. The recent clash over the veracity of the Panfilovtsy story also given many Russians a more nuanced understanding of their history even as some enjoyed the movie’s action sequences. Additionally, the 1948 investigative report that Mironenko had posted online, remains accessible on the website of the archive.

At the same time, many Russians are genuinely frustrated with what they perceive as the western ignorance of their elders’ sacrifices or what seems to them like the Ukrainian attempt to rewrite the script of the Victory Day. In this respect, they are inadvertently playing to their government’s line. This interaction between the political and the personal, family history and national narrative occurs in every society but in Russia seems particularly explicit because the fall of the Soviet Union shattered Soviet identity, creating an urgent need for a new one. While the current administration is eager to supply the new formula, based on my recent experience in Moscow, Russian citizens are still negotiating.

Agnieszka Smelkowska is a Ph.D candidate in the History Department at UC Berkeley, where she is completing a dissertation about the German minority in Poland and the Soviet Union while attempting to execute a perfect Passata Sotto in her spare time.

Leave a Reply