by guest contributor Megan Baumhammer

The fieldwork expeditions of William Beebe (1872- 1962) and the Department of Tropical Research aimed to “bring the laboratory to the jungle.” Beebe, an ornithologist affiliated with the New York Zoological Society (now known as the Wildlife Conservation Society), founded the Department of Tropical Research in the early twentieth century. From the beginning the DTR was part of a lineage of expeditionary, exploratory science after the model of Theodore Roosevelt and the safari-style collectors of the American Museum of Natural History and the Explorer’s Club. The New York Zoological Society poured resources into DTR expeditions to the Sargasso Sea, the Humboldt Current, the Galapagos, Haiti, Bermuda, and elsewhere around the world.

As Mark Dion, Katherine McLeod, and Madeleine Thompson–the curators of the Drawing Center’s exhibition “Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions” (at the Drawing Center in Soho until July 16, 2017)–made clear in their introductory notes to the exhibition’s catalogue, the expeditions were the investigative aspect of the DTR’s project. The DTR’s ultimate goal was to communicate the ecology of both tropical jungle and oceanic environments to broad audiences. In a remarkable presentation, the curators site the drawings generated by the expeditions within their own ecology, giving a sense of the the network of diverse actors (scientists, technicians, assistants, local guides, sailors, etc.) that produced the beautiful drawings on display. The exhibition space is divided into realms, such that half of the room covers the jungle expeditions and the other half covers the ocean expeditions, with a map in the middle tracing the geographic context.

Installation of Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions, Courtesy of The Drawing Center, Photo by Martin Parsekian, 2017

Installation of Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions, Courtesy of The Drawing Center, Photo by Martin Parsekian, 2017

Installation views of Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions, Courtesy of The Drawing Center, Photo by Martin Parsekian, 2017

Installation views of Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions, Courtesy of The Drawing Center, Photo by Martin Parsekian, 2017

The Beebe expeditions were supposed to bring the objectivity of the laboratory into the space of their investigations. The environments themselves would become the source of objective knowledge through scientific collecting, testing, and research. Beebe and his collaborators produced narratives of exploration that drew heavily on the sense of adventure and excitement that surrounded earlier, “romantic” naturalist traditions. The beautiful drawings that are the center of the exhibition were made in this context. The Drawing Center exhibition restages the groundbreaking, work done by this romantic and enterprising scientific research group within a highly aestheticized space.

Recreation of an artist’s workbench, Installation of Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions, Courtesy of The Drawing Center, Photo by Martin Parsekian, 2017

Recreation of an artist’s workbench, Installation of Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions, Courtesy of The Drawing Center, Photo by Martin Parsekian, 2017

Visitors enter an exploratory space that evokes a mix of different figures and aesthetics, from Jacques Cousteau, Maria Sybilla Merian, and Alfred Russel Wallace to Wes Anderson’s fictional Cousteau doppelgänger, Steve Zissou. Curatorial attention to the environment surrounding the expeditions highlights several issues currently in conversation in the History of Science: women in science; science and colonialism; representation in images and science communication.

All of these elements have been a part of the drawings’ world since they were put into circulation, however this exhibition adds a critical dimension to their presentation of the material. The curators show that women artists, scientists, and technicians played a central role, and that women were hired because of their aptitude and experience. They also argue that the gendering of expedition participants’ roles reinforced the explorative masculinity of the enterprise and of William Beebe, since he wanted “adaptable scientific students who fall in with my plans” on his expeditions. The curators also highlight the colonial nature of the DTR’s scientific enterprise through comments and other materials by DTR scientists and artists. A map detailing the DTR’s sites of scientific practice reinforces the colonial context that both framed and enabled the group’s work.

The artwork produced by the DTR was clearly both a tool for research and a means for communicating and disseminating findings about the ecology of the ocean or jungle.

Helen Damrosh Tee-Van, “Snapping Shrimp and Family,” Bermuda, 1931. Watercolor on paper, 14 1/2 x 11 1/2 in. (37 x 29 cm). Courtesy of the Wildlife Conservation Society. Photograph by Martin Parsekian.

Helen Damrosh Tee-Van, “Snapping Shrimp and Family,” Bermuda, 1931. Watercolor on paper, 14 1/2 x 11 1/2 in. (37 x 29 cm). Courtesy of the Wildlife Conservation Society. Photograph by Martin Parsekian.

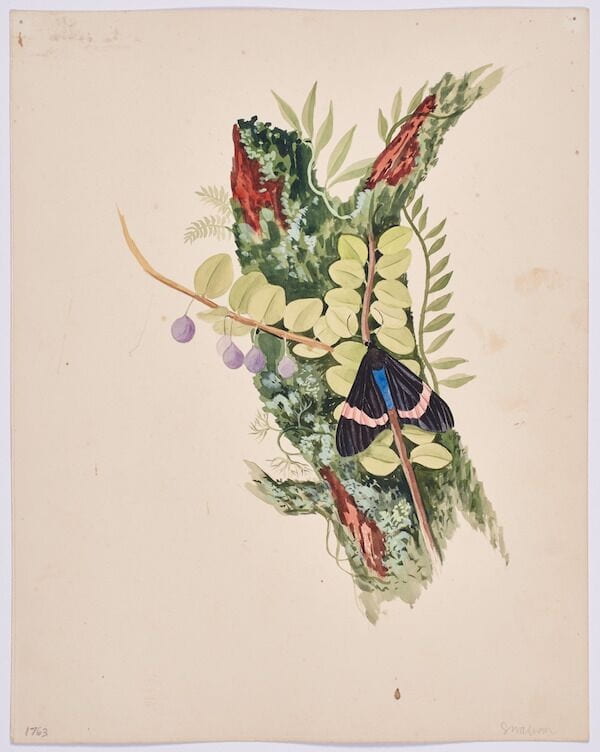

At the beginning of the twentieth century these drawings provided a clarity of form and color that photography was unable to convey. But not all of the drawings were produced to satisfy the standards of scientific illustration. DTR artists occasionally took creative liberties, and some of the drawings, such as George Swanson’s Leaf-like Mantis, include jokes. In Swanson’s drawing, a mantis dances around the lower half of the page following the movements of ballet. However, Swanson retained the representational conventions of scientific illustration, and the repeated drawing of poses on this page is exactly like those elsewhere sketched by the DTR artists to record the movements of other animals, such as fish. The joke of a mantis performing ballet looks just like the record of fish as a specimen for future study. Parsing the differences between a joke and scientific illustration thus requires both a certain expertise and knowledge, and familiarity with both the drawing’s context and its community.

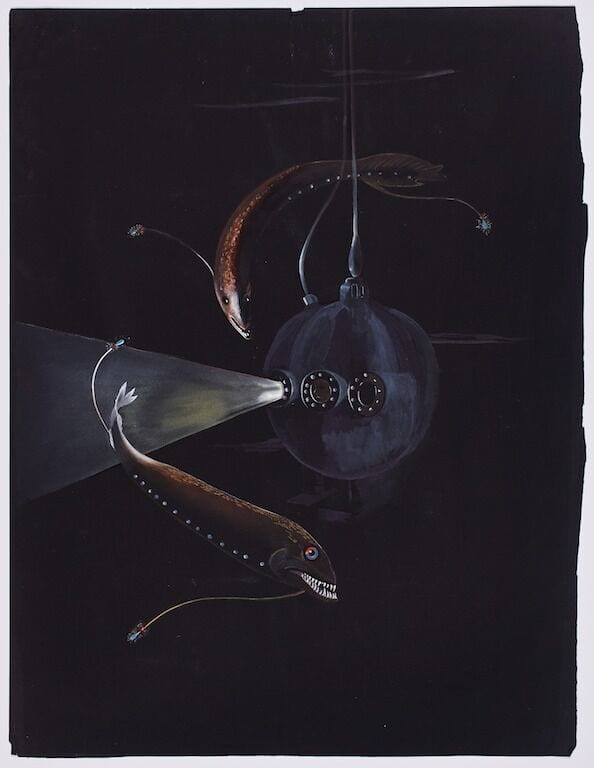

One of the most intriguing elements of the exhibition, to me, is the question of representation and imagination. The exhibition explores the theme of the imaginative space generated by and for the images. Margaret Cohen has noted the difficulty that Beebe had in communicating the unseen space found beneath the sea, either because the unfamiliar environments were difficult to describe or because it behooved Beebe to use the descriptive difficulty itself as a rhetorical tool. The curators argue that the drawings themselves are mediated and directed artifacts of research rather than direct representations. The drawings served as a link between the scientists and a reading, viewing, funding public, who accessed these spaces of research through popular magazine articles and Beebe’s bestselling books. Equally important, the images were often produced through second-hand descriptions of the phenomena, although this would have been less apparent to the public. For example, William Beebe descended to the deep sea, but the artists who drew the deep sea did not. Instead Beebe described the underwater world to the artist, who then drew it. These drawings relied entirely on Beebe’s textual cues. They are, in many ways, pure products of the artist’s imagination. This is most obviously demonstrated in Else Bostelmann’s Bathysphere intacta (Circling the Bathysphere), which depicts an impossible situation: the artist is situated outside of the protective Bathysphere diving bell, fixed by the eye of a deep-sea creature.

Else Bostelmann, “Bathysphere Intacta (Circling the Bathysphere),” Bermuda, 1934. Watercolor on paper, 18 1/2 x 24 1/2 in. Courtesy of the Wildlife Conservation Society. Photograph by Martin Parsekian.

The imaginative space of the deep ocean is here reflected in the imaginative space necessary to create it. The image compounds–and highlights–the artificiality of the artist’s experience.

The work of William Beebe and the Department of Tropical Research was a remarkable enterprise of the first half of the twentieth century. The images alone would be worth an exhibition, their beauty and color and character are so absorbing. They conveyed the first sense of a completely unknown life in the deep ocean and a further exploratory sense of the jungle or coastline. The curatorial framing of the drawings enables the visitor to see the work of the Department of Tropical Research clearly within its own context. The images are presented as a glorious production of the colorful, complicated DTR community. The group’s participation in the ongoing colonial relationship between the US and South America, underscored by the locations of its field stations, was an inextricable part of the drawings made from fieldwork, as was the group’s the “exploratory spirit” and its desire to know more about nature. The beautiful, striking images, combined with the self-presentation of William Beebe and his work, provide a world for the viewer’s imagination. Their audience found them thrilling because along with scientific knowledge of new and unfamiliar places, they provided a measure of romance as well. The images provided viewers with a means to recreate the experiences of the DTR crew. In their Drawing Center exhibition, the curators expose the distance between the various levels of an expedition’s documentation and self presentation. The exhibition pulls apart the interlocking framework of the DTR’s work to better show the workings of each part. The finely rendered portraits of jungle creatures and underwater life are situated within the material culture produced by the DTR; the sociocultural makeup of the participants of DTR studies is shown alongside the films and visual images designed to communicate their work. This presentation lays bare the assumptions and work that contribute to the scientific representations we have come to take for granted, and if you would like to explore these same questions the exhibition is certainly worth seeing before it closes in July.

“Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions” is on view at the Drawing Center (New York, NY) through July 16, 2017.

Megan Baumhammer is a PhD candidate at Princeton University studying the history of science. She works on representative depiction in early modern science, and science and the imagination.

1 Pingback