by editor Erin McGuirl, and guest contributor Roger Gaskell

The Rare Book School Replica Copperplate Press, in the Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

In the inaugural issue of the Journal of the Printing Historical Society (1965), Philip Gaskell defined the bibliographical press as “a workshop or laboratory which is carried on chiefly for the purpose of demonstrating and investigating the printing techniques of the past by means of setting type by hand, and of printing from it on a simple press.” Just a few weeks ago, we had the honor and pleasure of inaugurating the bibliographical pressroom and exhibition space at the University of Virginia, in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Thanks to a collaboration between the University Library, Rare Book School, and the bookseller Roger Gaskell, UVa is now home to two bibliographical presses for use in public demonstrations, bibliographical instruction, and scholarly research. One is a common letterpress, used for printing text and images from type and relief blocks; the other is a rolling press, used for printing from intaglio plates. This is the first and only bibliographical rolling press, and it is a significant step for scholars not only of the history of printing, but also of the history of art, science, cartography, and other disciplines which rely on historical texts printed from intaglio plates, either exclusively or in combination with letterpress text.

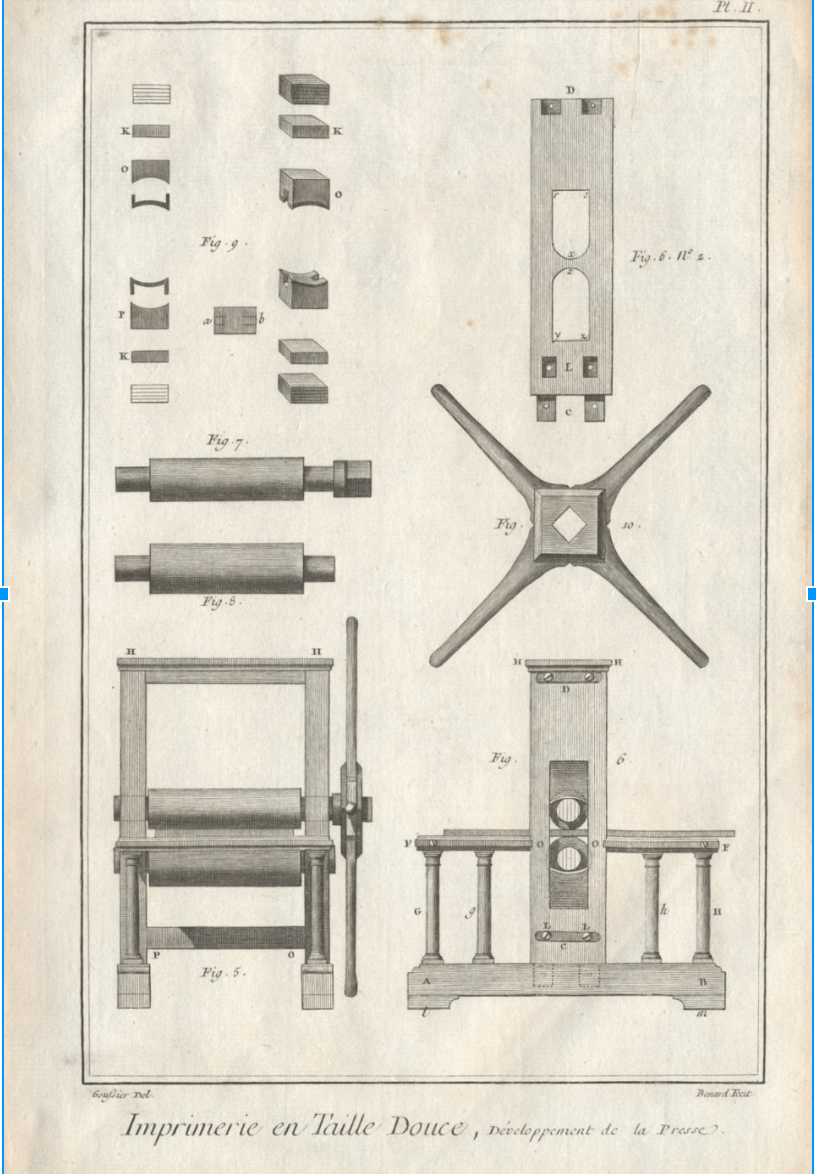

Roger Gaskell, a scholar and bookseller, designed the new bibliographical rolling press, a replica based on the designs published in Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie in 1769. As an antiquarian bookseller specializing in natural history and science books, Roger has always been interested in the production history and bothered by the lack of rigorous bibliographical language for the description of illustrated books. In 1999, a fellowship at the Clark Library in Los Angeles allowed him to study intaglio plates inserted into letterpress printed books, and he formed the idea then that building a replica wooden rolling press was essential for a better understanding of the mechanics and workshop practices of intaglio printing. Six years ago, Michael Suarez invited him to teach at Rare Book School and over dinner, Roger pitched to Michael the idea that Rare Book School should commission the building of a wooden rolling press based on a historical model. Some years later they discussed this again. But what to build? A press based on the design published by Bosse in 1645? That has been done: there is a fine replica in the Rembrandt House in Amsterdam that is frequently used for public demonstrations. A copy of an existing press? Gary Gregory was doing this for his Printing Office of Edes and Gill in Boston. It was the inspired suggestion of Barbara Heritage to build a press based on the Encyclopédie engravings. By good fortune Roger had seen a surviving press of very similar design on display in the print shop of the Louvre in Paris some years earlier. This made the Encyclopédie the perfect source as its accuracy, as well as a number of constructional details, which could be verified by examination of a contemporary press. The Chalcographie du Louvre press is now in storage at the Atelier des Arts, Chalcographie et Moulage at St Denis to the North of Paris where Roger spent a day photographing and measuring, in preparation for his new press.

Robert Bernard (b. 1734) after Jacques Goussier (1722–1799). Imprimerie en taille-douce, Développement de la Presse, in Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 7 (plates). Paris, 1769.

The Chalcographie du Louvre press at the Atelier des Arts, Chalcographie et Moulage at St Denis. Photograph by Roger Gaskell.

The use of working replicas gives students and researchers access to the technologies of book production that shaped the transmission of texts and images. Traditionally, the production of literary texts has driven the development of bibliography, bibliographical teaching, and the bibliographical press movement. But it has also long been understood that the ability to print images in multiples was as revolutionary for the development of other disciplines, including medicine, science, technology and travel literature, as the printing of texts has been to religious movements and imaginative literature. At UVa and Rare Book School, students and researchers can now work with the two – and only two – printing technologies responsible for all book production before the nineteenth century: relief and intaglio printing. There we can develop the habits of mind necessary to understand the implications of the extraordinary synergy of mind, body and machine which shaped the modern world in the west. Presses like these were used to print engravings and etchings for collectors, popular broadsides and ballads, indeed all kinds of ephemera as well as printed books.

Erin McGuirl, the rolling press, and prints in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, UVa

As a discipline, bibliography has been shaped by its leading scholars’ interests in English drama, poetry, and fiction, and in incunabula. Scholars working in the history of art and science, and anyone working with books on travel and exploration, are at a bibliographical loss – it’s hard to understand why an illustrated book came to be the way it is because bibliographical literature (with a very few exceptions) does not address the problems raised by printing in non-letterpress media. What’s more, this problem extends beyond rolling press printed matter and the handpress period and into twentieth century non-letterpress materials made on mimeograph, ditto, and Xerox machines. Much of the work by media historians is rightly viewed with skepticism by the bibliographical community, yet this community has not yet figured out how to think about printed matter that isn’t made from folded sheets of letterpress.

Printing is the work of the body as much as it is the work of the mind; it’s time to roll up our sleeves. Particularly in the absence of substantial archival records of rolling press printers and intaglio plate artists, we must get our bodies behind the press to confront the constraints of printing for books from intaglio plates. We need to print images and put them in books, we need to confront the reality of doing this in multiples (and probably also in debt), and in coordination with the production of letterpress text. Doing this work will make way for the kind of grounded thinking about print that makes for good scholarship.

Megan McNamee, RBS Mellon Fellow & A.W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery, pulls a print on the Rare Book School Copperplate Replica Press.

Roger Gaskell is a scholar and bookseller, now living and working in Wales. He teaches The Illustrated Scientific Book to 1800 course bi-annually at Rare Book School, and teaches a regular seminar, Science in Print in the Department of History and Philosophy at the University of Cambridge.

Leave a Reply