By guest contributor Emily Yankowitz

On December 30, 1806, on the inner cover of his first attempt at writing a historical work, the New Hampshire statesman William Plumer wrote, “An historian, like a witness, is bound to relate the truth, the whole truth, & nothing but the truth.” He would take up his project of writing a “History of North America” in November 1809 after three years of research. In what appears to be typical of Plumer’s personality, he intended to write a history of the United States government, but the project quickly expanding into “a general history of the United States” from its discovery by Europeans to his own time It was to include accounts of administrations, laws, presidents, heads of departments, members of Congress, judiciary, foreign relations, negotiations, relations with Indian tribes, purchases of lands, and commerce. Reaching even further into the past, he began with an overview of classical history, including the invention of hieroglyphics, and a detailed study of European political events, before arriving at the settlement of Jamestown in 1607 over 220 pages later. Yet having worked on the project for nine years and seeing little progress, Plumer unceremoniously put it aside, writing, “The undertaking I have abandoned” on the last page.

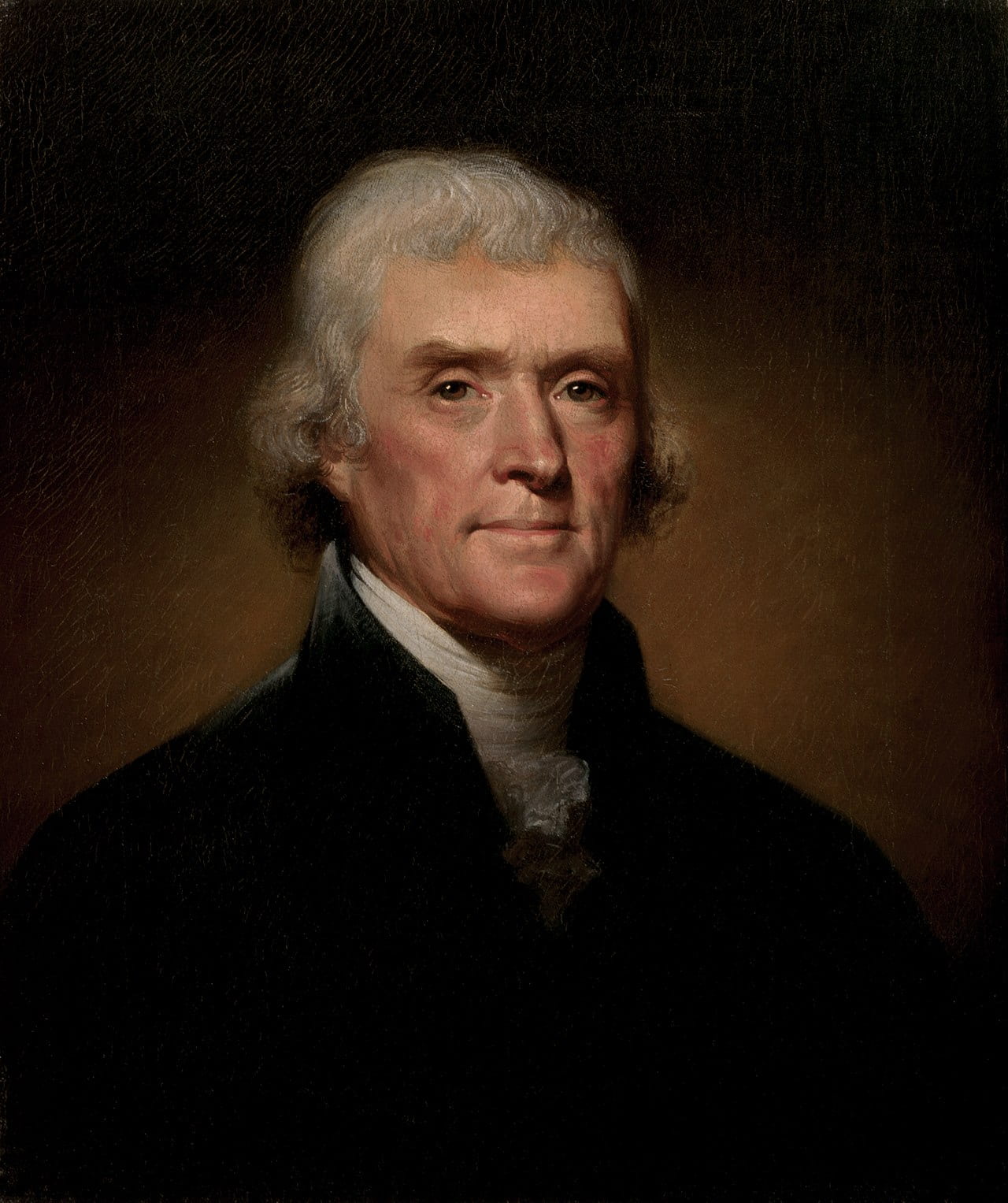

William Plumer, engraving by Charles Balthazar Julien Fevret de Saint-Mémin (1806). Photo credit: Library of Congress

A Federalist senator in a Congress dominated by President Thomas Jefferson and the Republicans, Plumer had little hope of influencing politics. Watching his vision of the world collapse around him, Plumer recalled that with nearly every measure Jefferson proposed, he was reminded of the angel’s declaration to Ezekiel, “Turn, & thou shall behold yet greater abominations” (Plumer to Jeremiah Smith, January 27, 1803, quoted in Turner, “Thomas Jefferson,” 207). These “abominations” included the Louisiana Purchase, the Twelfth Amendment, and the impeachment of New Hampshire judge John Pickering. Frustrated and alarmed, Plumer helped to plan a scheme for New England secession in 1803–1804, hoping to create a “Northern confederacy.” But the project quickly fell apart, although intransigent Federalists would take up a similar plan at the 1814–1815 Hartford Convention.

Amid a career in jeopardy and anxieties about the future, Plumer found solace in historical pursuits. Overwhelmed by his country’s fast-paced development, history offered Plumer a method of “preserving facts & opinions” that were “rapidly hasting to oblivion” as a result of the “changes & revolution of time and parties” (May 2, 1805). Unlike other senators who indulged in horse racing and gambling, Plumer spent his free time hidden for hours in the Congressional Library, reading voraciously. This curiosity was one of Plumer’s most pronounced traits; the son of a farmer, Plumer received little formal schooling beyond elementary studies, and pursued much of his education through books.

Over time, Plumer’s intellectual interests expanded. Spotting a mound of scattered government documents in the damp, mildewed lumber room above the Senate chamber, he devoted himself to preserving them, methodically sorting through the soiled records. Through the next four years, Plumer collected journals of every Congress from 1774 to his own, enough to fill between four and five hundred bound volumes. He eventually came to possess one of the largest and most complete collections of public papers held by a private citizen, even after he donated a substantial amount to the Massachusetts Historical Society. This effort rescued valuable documents from destruction, and also provided Plumer with a substantial number of sources for his later historical works. According to his son, it was this collecting effort that inspired Plumer to write a history of the country (For more information, see Freeman, Affairs of Honor, 262-4).

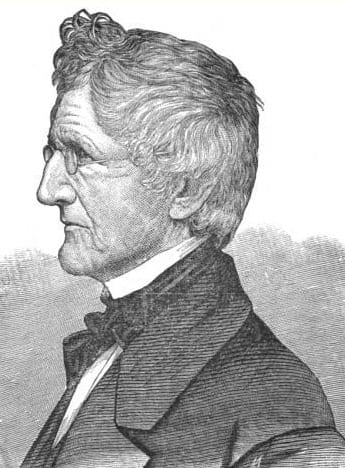

President Thomas Jefferson, painted by Rembrandt Peale (1800)

With the end of his term approaching, Plumer set about preparing for this enormous task—consulting with government officers, copying private letters shown to him by friends, and corresponding with antiquarians and scholars. He conferred with Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury, who offered him any materials needed from the Treasury department. Not everyone was supportive—at least one friend advised Plumer to publish his history posthumously to avoid giving “mortal offence” to contemporaries (February 28, 1807). His meeting with President Jefferson showed how complex the publication of his history might be. Plumer observed that Jefferson’s “countenance […] repeatedly changed.” Jefferson expressed “uneasiness and embarrassment—at other [moments] he seemed pleased.” Seemingly affected by a range of emotions, Jefferson alternated between looking at Plumer and staring at the floor. Jefferson’s reaction perplexed Plumer, who reasoned that Jefferson must have been “embarrassed,” and “disapproved” of the project (February 4, 1807). But he also discussed Jefferson’s strange response with John Quincy Adams, who informed him that Jefferson “cannot be a lover of history,” as he did not want certain “prominent traits in his character” and “important actions in his life” to be outlined and communicated to posterity (February 9, 1807). Jefferson’s own actions appear to echo this sentiment. Out of a desire to control how he would be remembered, Jefferson later professed to have “no materials whatever” for Plumer’s project despite its usefulness to the country.

Plumer’s background and personality did not make him a particularly obvious candidate for the project. In his diary, he mulled over his doubts about his efforts, noting his personal shortcomings, the complications of his private life, and the magnitude of the project. He was not a “scholar” or a “master of the English grammar,” he noted, and could not read any foreign language or express his ideas quickly on paper. Regarding his personal life, his wife was often sick and he himself had a “weak & feeble constitution.” However, Plumer was also highly aware of the shortcomings of existing “historic performances,” namely state histories, which were written too quickly. They contained factual errors, had a “loose & slovenly” style, and “fall short of the true style & dignity of history.” He found Benjamin Trumbull’s Complete History of Connecticut to be “written in the style of a low dull Chronicle,” while James Sullivan’s History of the District of Maine was a “jumble of fact & fable” (July 22, 1806). Yet his task would take “indefatigable industry, & patient labour to render it useful to others and honorable to myself.” Virgil took twelve years to write the Aeneid, Plumer worried, while Edward Gibbon took twenty years to write The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Plumer would exceed both Virgil and Gibbon, ultimately devoting the remainder of his life to historical works that ultimately remained unpublished.

While Plumer believed the work would be useful for “future statesmen,” he also hoped to enhance his reputation. If he successfully produced the work, it would be an “imperishable monument that would perpetuate” his name. Highlighting the inextinguishable impact of history, Plumer noted that it would exist when “columns of marble are dissolved & crumbled to dust.” However, if he did not execute it well it would “tarnish & destroy” the little “fame” he had acquired (July 22, 1806). Thus, writing history had political as well as personal consequences.

William Plumer, Jr., depicted in The Granite State Monthly (1889)

Plumer was not alone in using history to achieve a recognition he would never receive through politics. In fact, one of his sons, William Plumer Jr., would take up a similar project in 1830, after completing his term as a representative. Reflecting on the project, he noted that if “executed with any tolerable success, it would be a more important service rendered to the public than I can hope in any other way to perform” and he might be able to acquire a “reputation, however small” if the work was successfully produced (“Manuscript History of the United States”). While the boundaries of Plumer Jr.’s intended project were smaller (he planned to begin with Columbus’s voyage in 1492), he made little progress.

Unable to acquire national political fame, Plumer sought recognition through history, while also pursuing a political (though nonpartisan) agenda. Even after his formal political party had changed to the Republican position, Plumer retained much of his Federalist view of the world, in part because of his own distaste for partisanship and in part because he lived in Federalist-concentrated New England. In particular, much like the Federalists of the 1790s, Plumer never fully supported the existence of political parties, viewing them as agents of division that distracted men from effectively evaluating candidates based on their abilities. Just as Plumer disapproved of partisanship in politics, he also disapproved of it in historical writing. For example, he wrote that historians and biographers should have “no other object than faithfully narrate facts & justly delineate characters” for when they “stoop to the support of a party or a sect” their “facts are misstated and their reasoning is sophistry” (“May 25, 1808”). Plumer argued that a historian should be “of no party in politic’s [sic] … without prejudice, & have more judgement than fancy” (“October 1, 1807”). Thus, for Plumer, historians did a disservice not only to the integrity of their subject, but also to the influence of their work, if they espoused partisan views.

Looking a bit further into the nineteenth century, historians would divide over whether it was acceptable to combine history and politics. In particular, following the decline of the Federalist party and the rise of Andrew Jackson, New England historians attempted to use history as a mechanism of regaining the power and influence they had lost in politics. Some followed both paths, like George Bancroft, who pursued a political career while working on his History of the United States, while others such as William Prescott and Jared Sparks believed that the two disciplines were incompatible (Cheng, The Plain and Noble Garb of Truth, 36-41). However, many members of both groups believed that history could be used as a method of advancing political agendas.

In an attempt to save their party from destruction in the wake of the Hartford Convention, some Federalists wrote historical works that tried (largely unsuccessfully) to shape how posterity remembered the event. Prompted in part by the publication of Matthew Carey’s wildly successful The Olive Branch and the Nullification Crisis, Federalists turned to writing histories to justify their actions. These works included Theodore Lyman’s 1823 A Short Account of the Hartford Convention, Harrison Gray Otis’ 1824 Letters in Defence of the Hartford Convention, and the People of Massachusetts, and Theodore Dwight’s 1833 History of the Hartford Convention. However, these works were generally unsuccessful.

Eager to shape both policies and how they would be remembered, early American politicking occurred both in the halls of Congress and in the pages of books. Plumer hoped to play a central role in constructing the young nation’s emerging identity and its memories of the early figures of the founding era. Thus, his historical writings—which he would continue for decades after his failed “History,” but largely never publish—serve as a reminder that our very understanding of the past has often been shaped by the individuals in the moment who had the foresight to record it. Given how the historical discipline has changed over time, it is perhaps tempting to dismiss early historian’s writings. However, they nonetheless offer a useful perspective on how contemporaries perceived the world around them and how they wanted it to be remembered.

Emily Yankowitz recently graduated from Yale University and is an incoming M.Phil. student in American History at the University of Cambridge. She is interested in the intersection of politics, culture, and memory in the early American republic.

1 Pingback