By guest contributor Burkhard Conrad O.P.L.

Any history of ideas and concepts hinges on the observation that ideas and concepts change over time. This notion seems to be so self-evident that the question of why they change is rarely addressed.

Interestingly enough, it was only during the course of the nineteenth century that the notion of a history of ideas, concepts, and doctrines became widespread. Ideas increasingly came to be seen as contingent or “situational,” as we might phrase it today. Ideas were no longer regarded as quasi-metaphysical entities unaffected by time and change. This hermeneutic shift from metaphysics to history, however, was far from sudden. It came about gradually and is still ongoing.

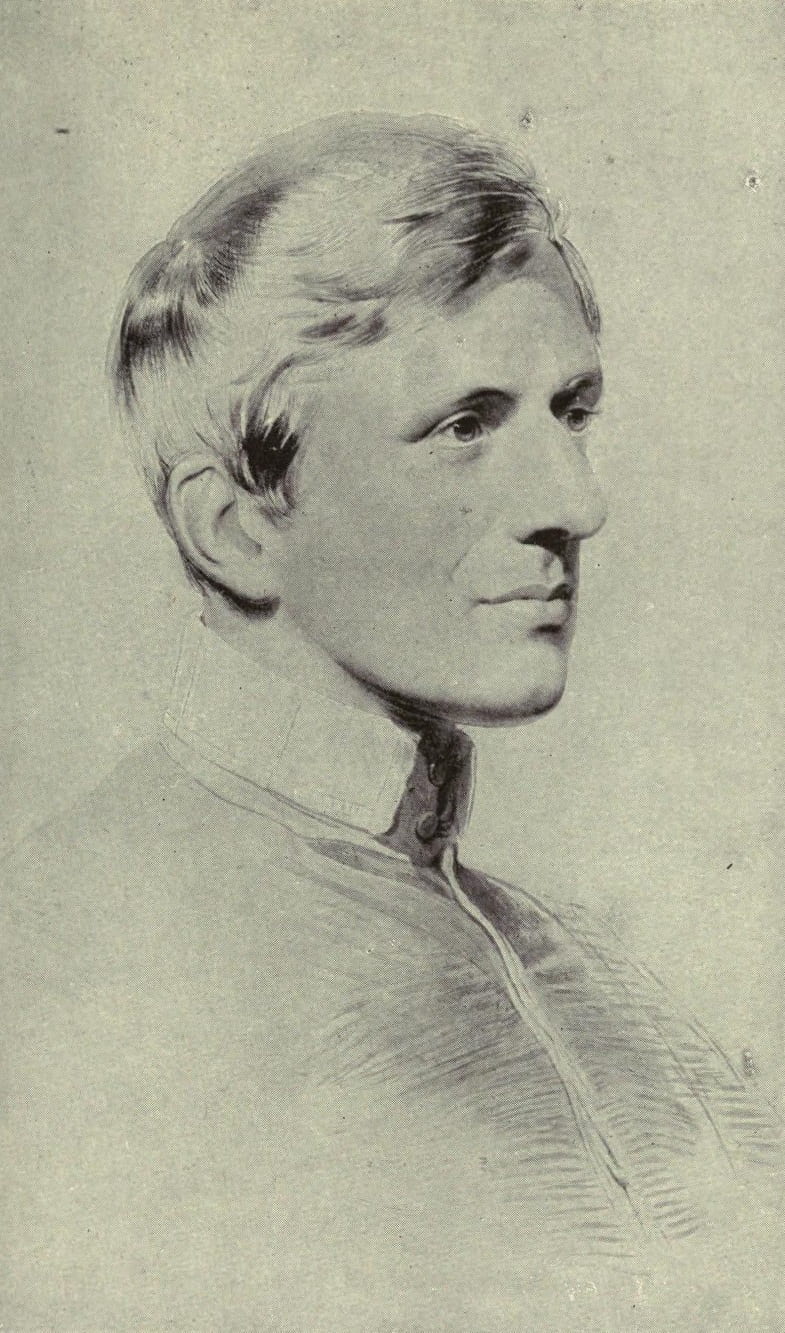

John Henry Newman in 1844, a year before he wrote his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (portrait by George Richmond)

The theologian and controversialist John Henry Newman (1801–1890) must be regarded as one of the intellectual protagonists of this shift from metaphysics to history. An eminent intellectual within the high-church Anglican Oxford Movement, Newman decided mid-life to join the Church of Rome, eventually to become one of the foremost voices of nineteenth century Roman Catholicism in Britain. Newman exerts an influence well into our time with figures such as Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) paying tribute to his thought. Benedict eventually beatified Newman in 2010.

Rarely quoted in any non-theological study in the history of ideas, Newman’s work is eminently important for understanding both the quest for a historical understanding of ideas and the anxious existential situation of those thinkers who found themselves in the middle of a momentous intellectual revolution. In Newman’s day, it was not uncommon for such intellectual and personal queries to go hand in hand.

In Newman’s case, this phenomenon becomes particularly obvious when we look at his contribution to the history of ideas. In 1845, during his phase of conversion from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism, Newman wrote his famous Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. I wish to focus on two of Newman’s central claims within the Essay. Firstly, he states that it is justifiable to argue that doctrines and ideas change over time. Confronting a more “scriptural”—i.e. Protestant—understanding, Newman affirms that ecclesiastical doctrines hinge not only on the acknowledgement of divine, biblical revelations, but also on a tradition of teaching that has evolved since the early church. Newman writes in one of his sermons that “Scripture (…) begins a series of development which it does not finish; that is to say, in other words, it is a mistake to look for every separate proposition of the Catholic doctrine in Scripture” (§28). He complements this thought by adding in the Essay that “time is necessary for the full comprehension and perfection of great ideas” (29), which is to say that doctrine is not something given only once, but rather possesses a dynamic quality.

But why does doctrine evolve in the first place? Why is it important to speak of a history of ideas? It is remarkable that Newman answers those questions in much the same way as we would do today. Doctrine, according to Newman, is ever-evolving because there is a need for such transformation. Ideas are simply “keeping pace with the ever-changing necessities of the world, multiform, prolific, and ever resourceful” (56).

Newman speaks of “a gradual supply [of doctrine] for a gradual necessity” (149). The logic behind doctrinal change may thus be explained as follows: a given or conventional doctrine comes into contact with or is challenged by alternative expressions of doctrine. These alternative expressions come to be regarded as false, as heresy. Hence, an adequate doctrinal reaction is necessary. This reaction may take the form either of a doctrinal change through the absorption of novel thought, or of a transformation through counter-reaction. Hence, Newman is even able to rejoice in the fact that false teaching may arise. He writes in the aforementioned sermon: “Wonderful, to see how heresy has but thrown that idea into fresh forms, and drawn out from it farther developments, with an exuberance which exceeded all questioning, and a harmony which baffled all criticism”(§6).

Hans Blumenberg © Bildarchiv der Universitätsbibliothek Gießen und des Universitätsarchivs Gießen, Signatur HR A 603 a

The necessity for doctrinal development, hence, is born within situations of discursive tension. These situations—the philosopher Hans Blumenberg once called them “rhetorical situations” (Ästhetische und metaphorologische Schriften, 417)—demand a continuous, diachronical stream of cognitive solutions. The need has to be answered. As Quentin Skinner once noted, “Any statement (…) is inescapably the embodiment of a particular intention, on a particular situation, addressed to the solution of a particular problem, and thus specific to its situation in a way that is can only be naïve to try to transcend” (in Tully, Meaning and Context, 65). The need for development and change, thus, is born in distinctive historical settings with concrete utterances and equally concrete counter-utterances. That is why ideas and concepts change over time: they simply react. “One proposition necessarily leads to another” (Newman, Essay, 52). This change is required in order to come to terms with new challenges, both rhetoric and real.

To be frank, Newman would hardly agree with Skinner on the last part of his statement, namely, that statements are never able to transcend their particular context. For all his historical consciousness, Newman was, like most his contemporaries, fixated on the idea that, despite its dynamic character, the teaching of the Church forms a harmonious, logical and self-explaining system of thought, a higher truth. He writes, “Christianity being one, and all its doctrines are necessarily developments of one, and, if so, are of necessity consistent with each other, or form a whole” (96).

Newman was also convinced—again contrary to Quentin Skinner—that the history of theological ideas had to be looked at with a normative bias. He identified certain “corruptions” in the history of theological ideas (169). It was important to Newman to be able to distinguish between “genuine developments” and these “corruptions.” A large part of his Essay is devoted to setting out apparently objective criteria for such a normative classification.

Who is to decide what is genuine and what is corrupted? Newman’s second claim in the Essay deals with this question. According to Newman, the only true channel of any genuine tradition is found within the Roman Catholic Church, with the pope as the final and supreme arbiter. Newman could not do without such a clear attribution of doctrinal decision-making power. It was necessary “for putting a seal of authority upon those developments;” that is, those which ought to be regarded as genuine (79).

In consequence, Newman mobilized his first claim about the dynamic nature of doctrines with regard to his second claim, the idea of papal infallibility in deciding matters of doctrine. It was clear even to the nineteenth-century theologian that the notion of papal infallibility was not explicitly contemplated by anyone in the early Church. But, according to Newman, the requirement for an “infallible arbitration in religious disputes” became more and more pronounced as centuries of doctrinal disputes passed (89). And Newman says of his own century that “the absolute need of a spiritual supremacy is at present the strongest of arguments in favour of the fact of its supply” (89). The idea of infallibility thus came into existence because, according to Newman, it was needed to settle doctrinal uncertainty within his own time.

Cardinal John Henry Newman, painted in 1889 by Emmeline Deane

Having admitted the pope’s supremacy in matters of doctrine, a consequent existential decision by Newman had to follow. He had no choice but to leave Canterbury for Rome. It is only fair to say that Newman required the idea of a final arbitrator, someone to decide on genuine doctrinal development, in order to fulfill his own need for certainty and a spiritual home. Even a sympathetic interpreter like the historian and theologian Jaroslav Pelikan had to concede “that here Newman’s existential purpose did get in the way of his historical vision” (Development of Christian Doctrine, 144).

And so Newman’s account of a history of ideas developing according to need was born as much out of an intellectual interest in the history of theological ideas as it was triggered by biographical motives. But which twenty-first-century scholar in the humanities could claim that his or her research interests had nothing to do with personal circumstances?

Burkhard Conrad O.P.L., Ph.D., taught politics at the University of Hamburg, Germany. He is now an independent scholar working for the archdiocese of Hamburg. Among his research interests are political theology, Søren Kierkegaard, and the Oxford Movement. He is a lay Dominican and writes a blog at www.rotsinn.wordpress.com.

4 Pingbacks