Category Broadly Speaking: A Companion Interview

Tejas Parasher in conversation with Grant Wong about his recent JHI article, “M. N. Roy and the Problem of Parliamentary Democracy”

Daniel Luban and Alexander Collin discuss his recent JHI journal article “Prisoner, Sailor, Soldier, Spy: Hobbes on Coercion and Consent.”

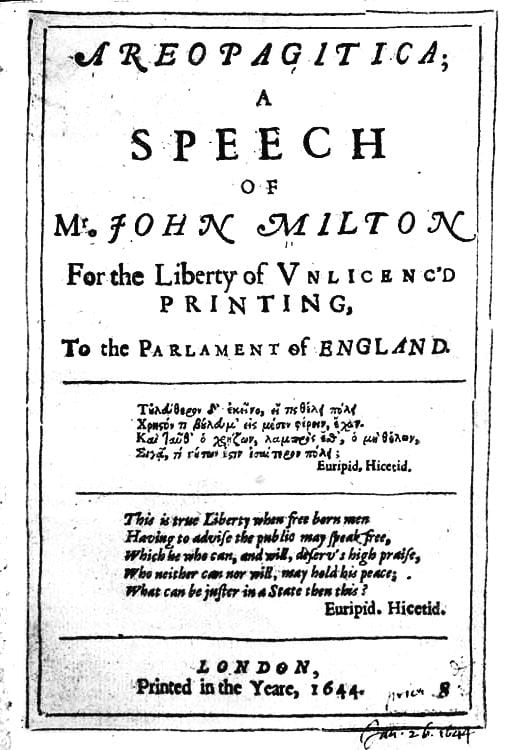

Ruby Lowe and Grant Wong discuss her recent JHI article “The Speech without Doors: A Genre, 1627–1769.”

Alexander Collin interviews Benjamin Woodford about his recent JHI article, “The right we have to our owne bodies, goods, and liberties: The Freedom of the Ancient Constitution and Common Law in Milton’s Early Prose”

Nuala Caomhanach interviews Felix Schlichter about his recent JHI article, “Euhemerus and Euhemerism in the Seventeenth and Eighteeth Centuries” (volume 84, issue 4).

Ana Antić in discussion with Tom Furse about her review essay, “Psychiatry and Decolonization: Histories of Transcultural Psychiatry in the Twentieth Century,” published in the January 2024 issue of the journal.

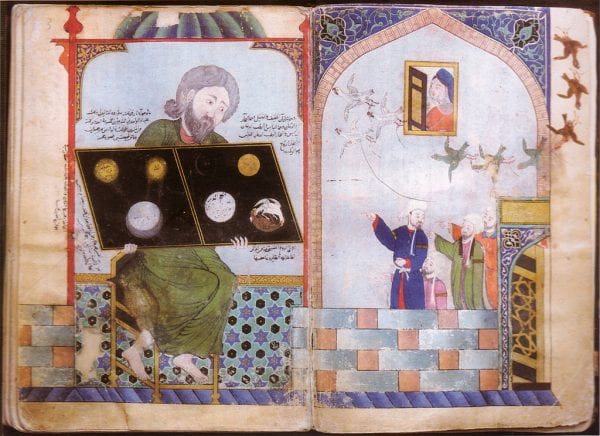

Alexander Collin interviews Alexandre Roberts about his recent JHI article, “Thinking about Chemistry in Byzantium and the Islamic World.”

Alec Israeli interviews Joyce E. Chaplin about her review essay considering recent books on the concept of the Anthropocene. (Part two of a two-part interview.)

Alec Israeli interviews Joyce E. Chaplin about her review essay considering recent books on the concept of the Anthropocene. (Part one of a two-part interview.)