Category Broadly Speaking: A Companion Interview

Grant Wong interviews Charles H. Clavey about his recent JHI article, “‘The Stereotype Takes Care of Everything’: Labor Antisemitism and Critical Theory During World War II.”

Luke Wilkinson interviews Nicolas Guilhot about his JHI article, “A Primitive Kind of Superstition: The Idea of the Paranoid Style in Art, Psychiatry, and Politics” (volume 84, issue 2).

Charlotta Forss in discussion with Cynthia Houng about her recent JHI article, “Mapping Atlantis: Olof Rudbeck and the Use of Maps in Early Modern Scholarship”

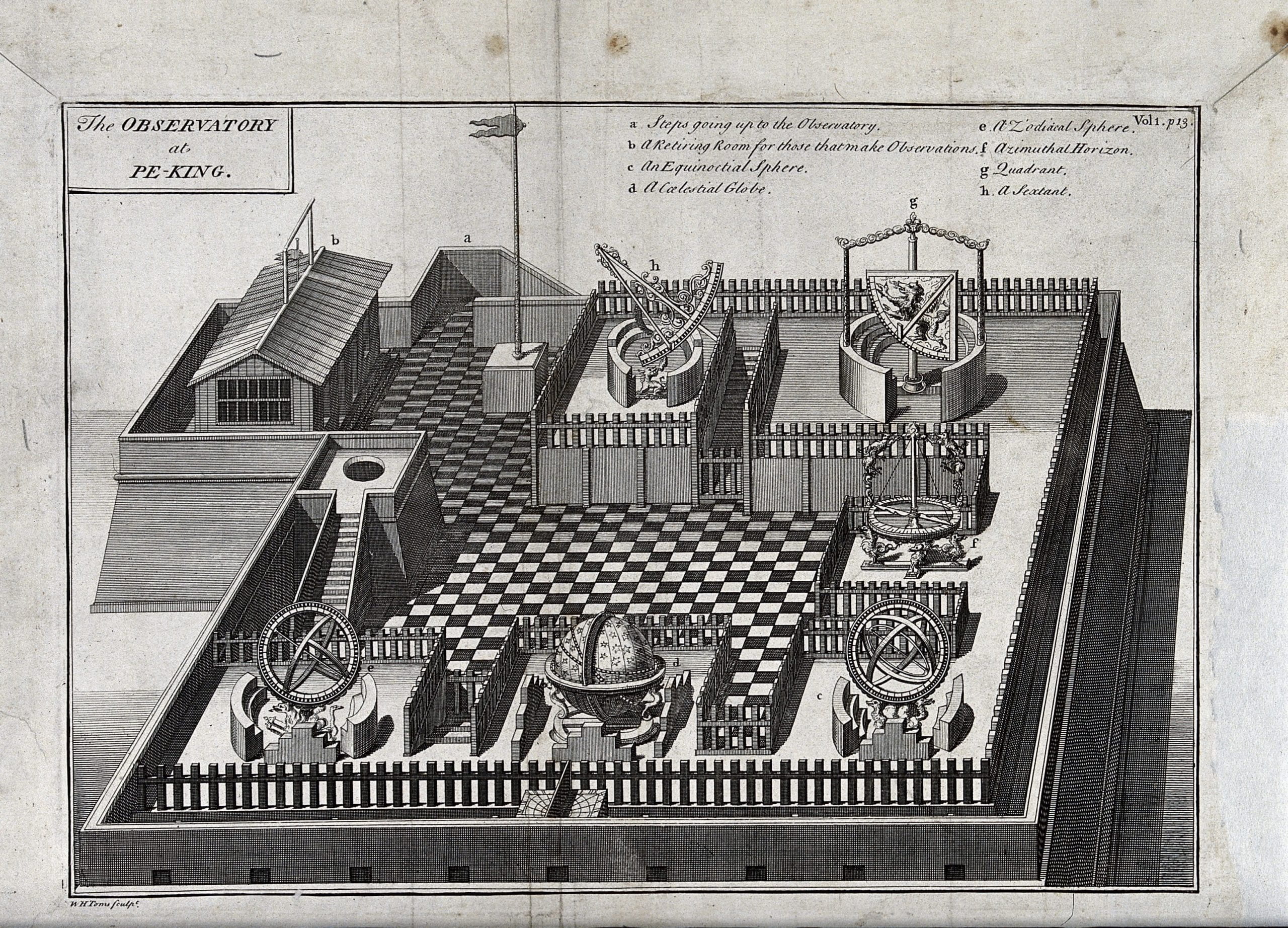

Gianamar Giovannetti-Singh in discussion with Alexander Collin about his recent JHI article, “Astronomical Chronology, the Jesuit China Mission, and Enlightenment History”

Michael Brinley in discussion with Alexander Collin about his recent JHI article.

Zvi Ben-Dor Benite in discussion with Alec Israeli about his recent JHI article.

Sarah Mortimer in conversation with Alexander Collin about her article in JHI volume 83, issue 4.

William Theiss in conversation with Nicholas Barone about his article in JHI volume 84, issue 1.

Roel Konijnendijk and Fernando Echeverría in conversation with Alex Collin about their article in JHI volume 84, issue 1.

Giuseppe Marcocci in conversation with Elsa Costa about Marcocci’s article in JHI volume 83, issue 4.