Category Companion Piece

By Seyla Benhabib, Andrew Gibson, and Artur Banaszewski

by guest contributor Justin Willson

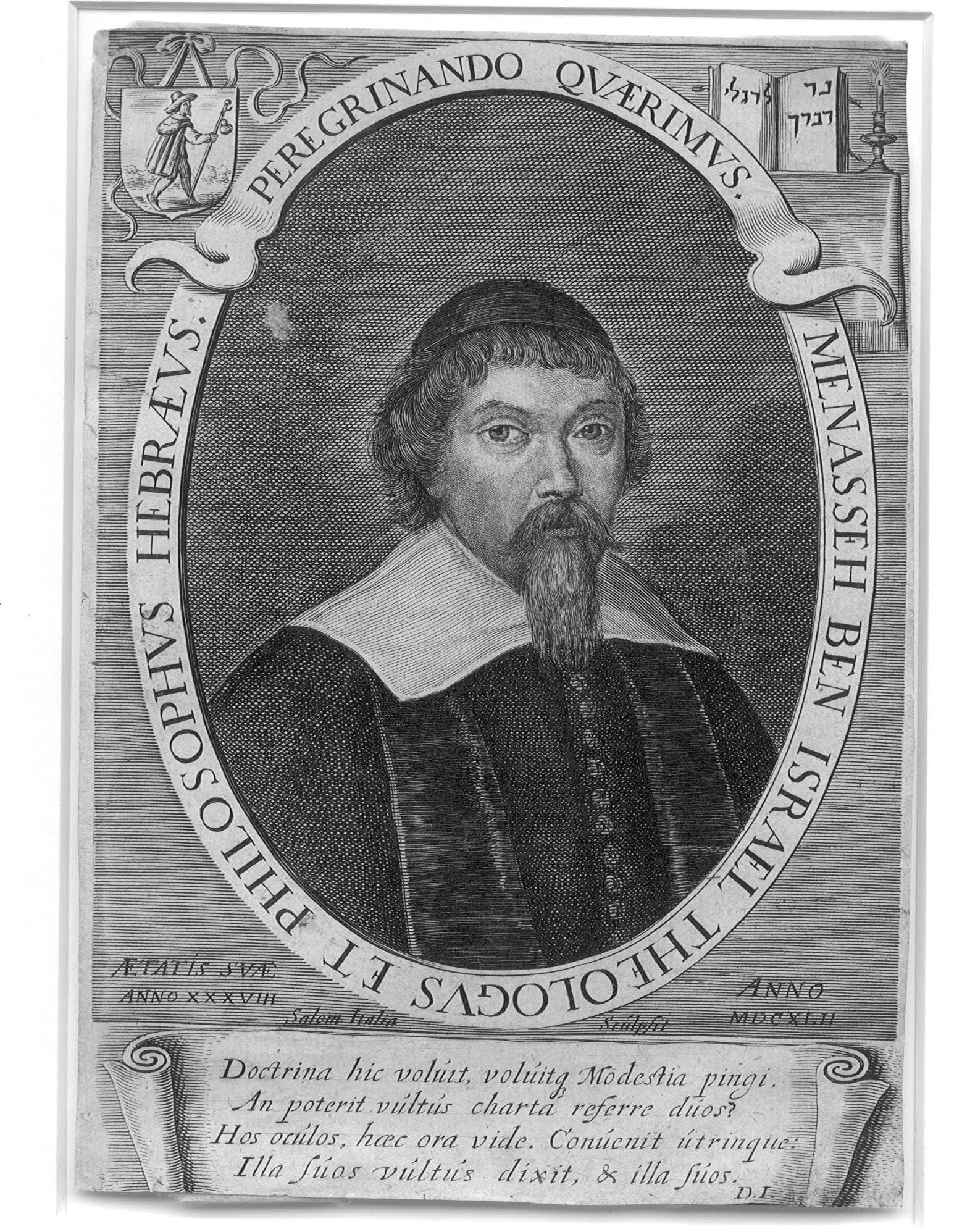

By Professor Steven Nadler Read Professor Nadler’s full article from this season’s JHI, “Spinoza and Menasseh ben Israel: Facts and Fictions.” It just goes to show: even a rabbi can sometimes bend the truth a little, especially in the heat… Continue Reading →

By Co-Hosts Simon Brown and Disha Karnad Jani In the past few months, we’ve had the opportunity to speak with several scholars on their new and forthcoming work, and we’ve found these conversations surprising, entertaining, and intellectually exciting. Through these… Continue Reading →

By Daniel Weidner This is a companion piece to Daniel Weidner’s recent article in the Journal of the History of Ideas, ‘The History of Dogma and the Story of Modernity: The Modern Age as the “Second Overcoming of Gnosticism”. Like identical… Continue Reading →

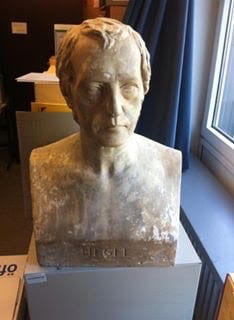

By Nicholas Germana Professor Germana’s essay “The Creuzerstreit and Hegel’s Philosophy of History” is in the most recent Journal of the History of Ideas. In his July 2002 article in JHI, on “Greek Origins and Organic Metaphors: Ideals of Cultural… Continue Reading →

By Zach Bates This is a companion essay to the author’s “The Idea of Royal Empire and the Imperial Crown of England, 1542–1698”, published in the January 2019 edition of the JHI. Into the twenty-first century, it has been a… Continue Reading →

This essay is a companion piece by Daniela K. Helbig for the article, ‘Life without toothache’, in the latest issue of the Journal of the History of Ideas, 80/1 (2019), 91-112. Writing tools: between the history of ideas and media theory Openly… Continue Reading →

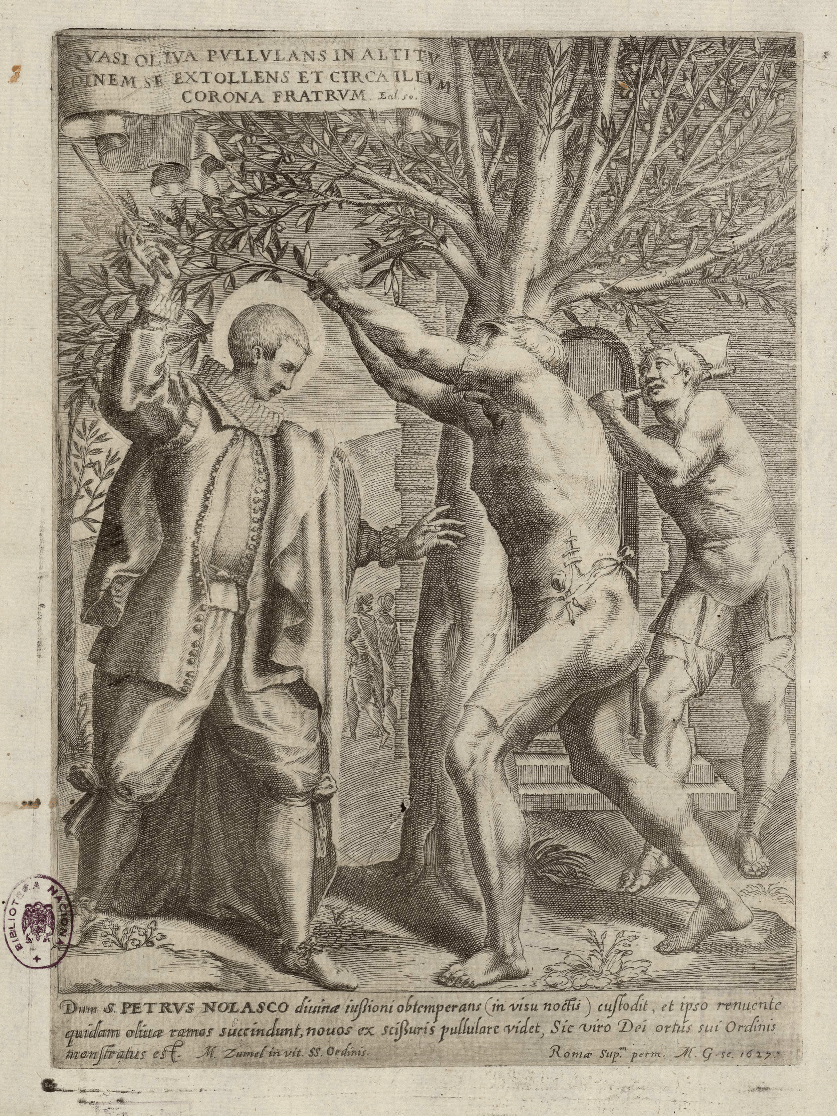

By Editor Spencer J. Weinreich This post is a companion piece to Spencer’s article in volume 80, number 1 of JHI, “Hagiography by the Book: Bibliomancy and Early Modern Cultures of Compilation in Francisco Zumel’s De vitis patrum (1588).” He slept, and was… Continue Reading →

by guest contributor Marco Menin Paul et Virginie, or the Misfortune of Religious Enlightenment The first time I read Paul et Virginie I was nearly ten years old, attending elementary school in a small town in Northern Italy. Among the… Continue Reading →