Category

What We’re Reading

This month: on Tolstoy and antiwar movements, ecological and social resilience, “The Care Manifesto”, imperial subjugation, “decadence,” and Asian Americans in US History.

This month: on “simple believers,” artificial intelligence, decolonial feminism, and the politics of antisemitism in Germany.

This month: on the intellectual biographies of Said, Sahlins, and Marx; critiques of Keynesian economics; and the politics of water control.

This month: on “memory wars” and Eastern European politics, the role of ideology in progressive histories of the 20th century, and the performance of professionalism.

This month: on historical analogies of fascism and democracy, the joys of surrealist symbolism, and Ferlinghetti’s San Francisco.

This month: the ongoing “fascism debate,” memory and the Holocaust, agrarian dispossession, liberalism, and Wagner.

This month: Milton’s political thought, Bloch & Aristotelian traditions, contextualized nationalisms, human cytogenetics, and radiation exposure.

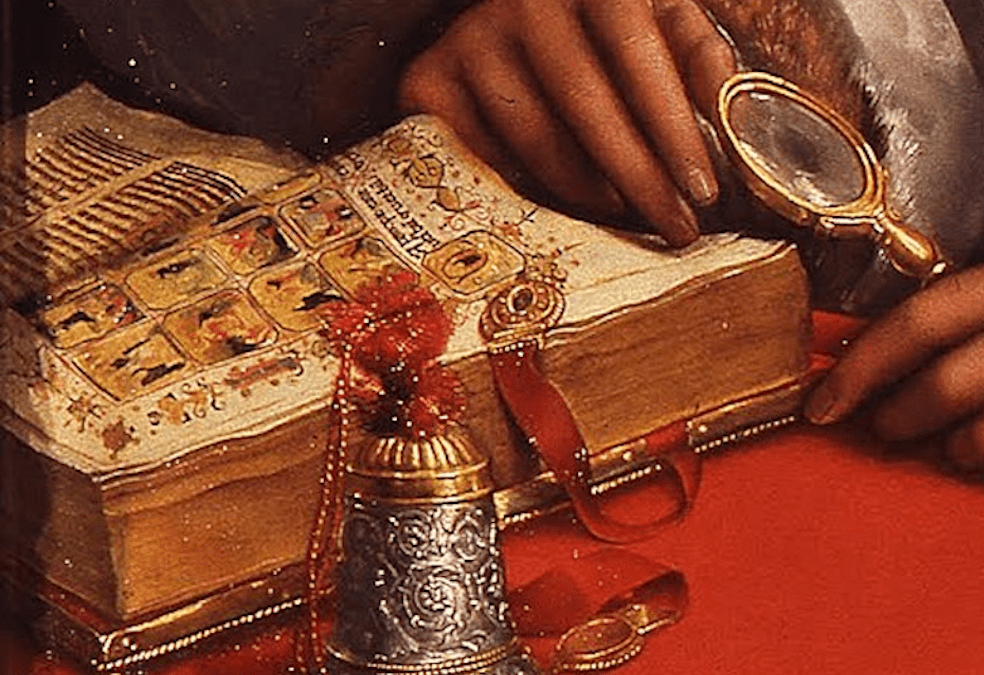

This month: stories of ghosts, reanimated ideologies, declinist narratives, and devotional books.

This month: on David Graeber, concepts of crisis, the immaterial in historical sources, and early Christians’ relationship to wealth.

This month: from John Lewis, Danny Lyon, and Paul Fusco, to the agendas of early-modern Aristotelianisms , remote work and capitalist labor.