Tag Art History

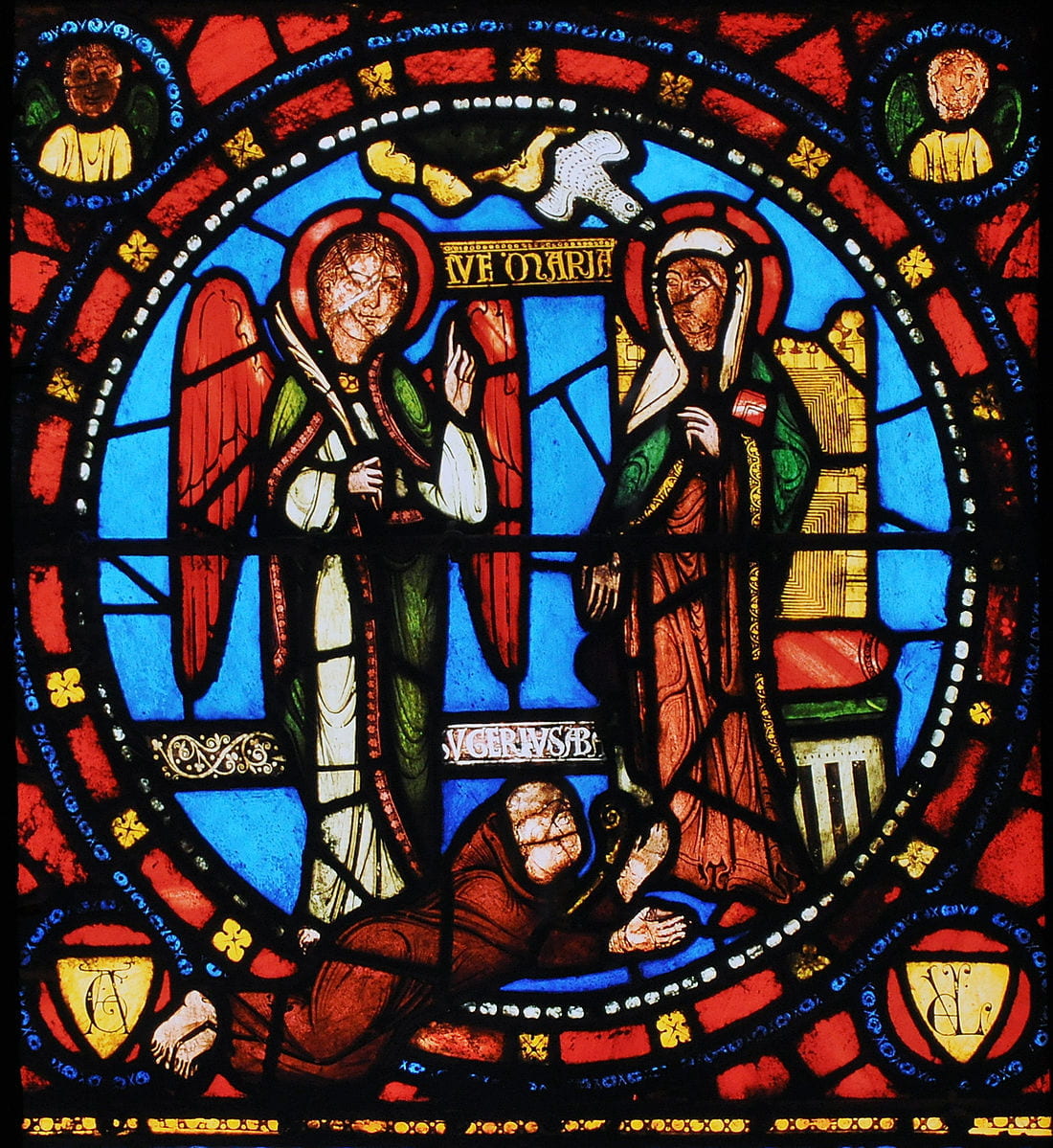

By Contributing Editor Cynthia Houng I first encountered Abbot Suger: On the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures, edited, translated and annotated by Erwin Panofsky (1946, 2nd. revised and expanded edition 1979) when I was working on a… Continue Reading →

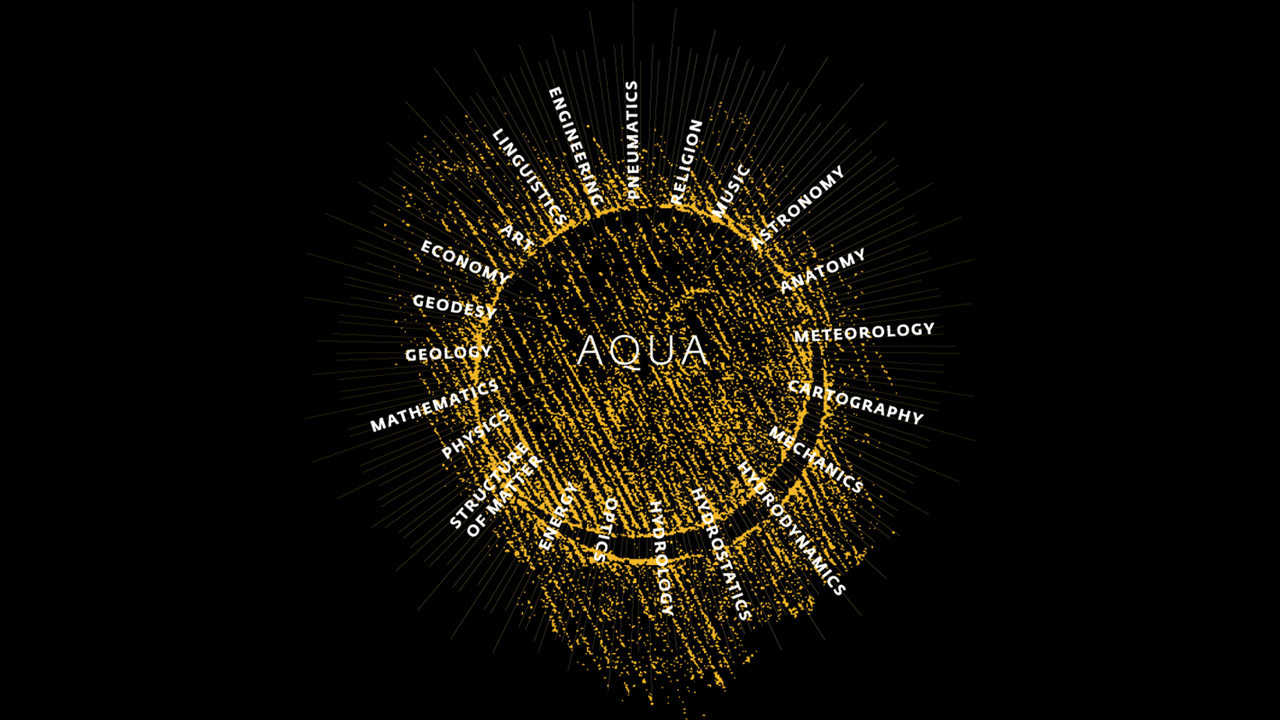

By contributing editor Luna Sarti This year several events will take place across the world to celebrate Leonardo da Vinci on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of his death. In Florence, where Leonardo lived and worked for several years,… Continue Reading →

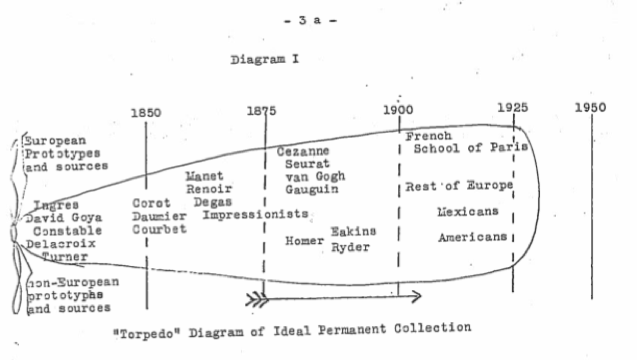

By guest contributor Edward Maza In a 1953 letter, Alfred H. Barr Jr.—the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art—wrote: “in our civilization with what seems to be a general decline in religious, ethical, and moral convictions, art… Continue Reading →

All photographs by Enrique Ramirez, click to enlarge + read captions By guest contributor Enrique Ramirez There was a moment upon entering Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams, currently at MoMA until January 1, 2019, when I felt as if I… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Hannah Leffingwell As I walk through the rain toward the neon sign reading BOOKS, I am aching for some guidance—or what might otherwise be called “theory”—in the likeness of a known name. Having just left the David… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Jonathan Potter Reviewing the 1842 Royal Academy of Arts exhibition, the art critic John Eagles wrote of J. M. W. Turner’s paintings: They are like the “Dissolving Views,” which, when one subject is melting into another, and… Continue Reading →

By Contributing Editor Cynthia Houng In Rome, Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) is nearly unavoidable. Walk down the center of the Piazza S. Pietro and look up. All along the great curving wings of the Piazza’s colonnades stand Bernini’s saints–carved and… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Joshua S. Daugherty While exploring the pictorial depth displayed in traditional Tibetan scroll paintings known as thangkas, a rather abstract concept continually resurfaced: the notion of space. Early paintings appear shallow or flat, yet, in later centuries,… Continue Reading →