Tag Book History

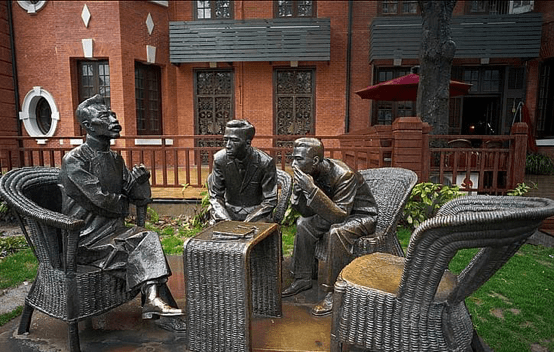

By guest contributor Joshua Fogel Several years ago, I was invited to give a paper at a workshop organized by graduate students at University of California, Berkeley. The topic was friendship in East Asia—with no specified time period or country… Continue Reading →

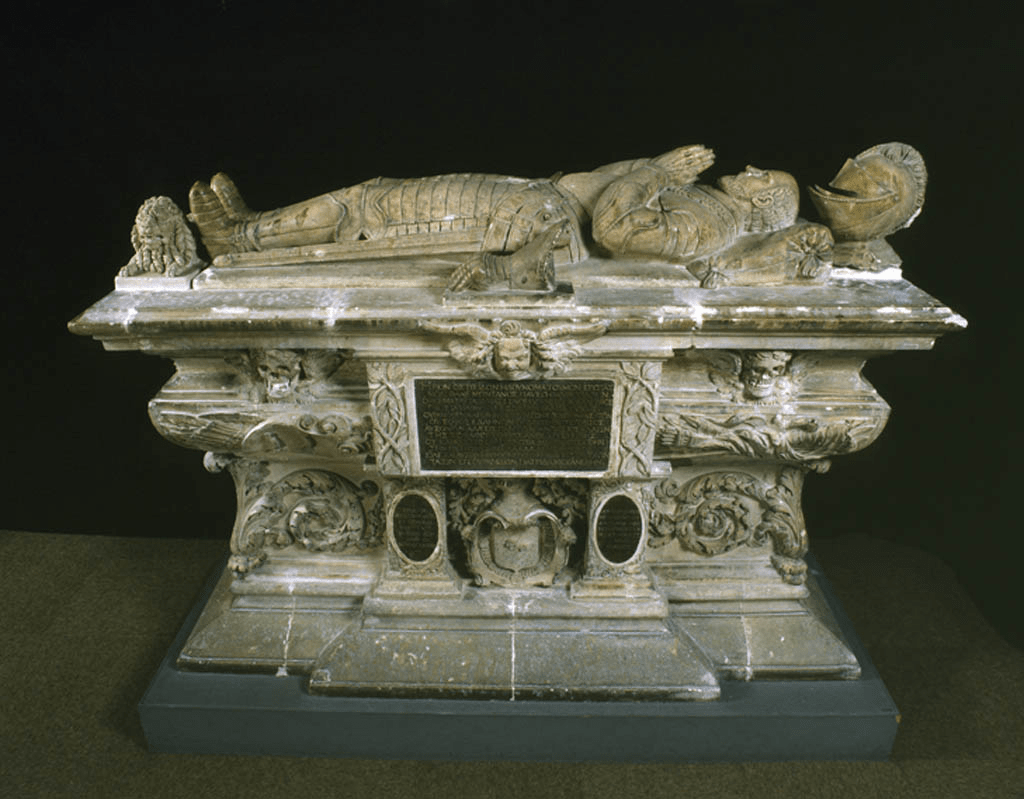

By guest contributor Max Norman On November 16th, Alain Juppé, mayor of Bordeaux, made an important announcement: the bones of Michel de Montaigne have been discovered. Or, at least, the bones might have been discovered. “Let’s keep our cool,” said… Continue Reading →

By Editor Spencer J. Weinreich Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo’s La ciencia española (first ed. 1876) is a battlefield long after the guns have fallen silent: the soldiers dead, the armies disbanded, even the names of the belligerent nations changed beyond… Continue Reading →

By Editor Spencer J. Weinreich Four enormous, dead doctors were present at the opening of the 2017 Joint Atlantic Seminar in the History of Medicine. Convened in Johns Hopkins University’s Welch Medical Library, the room was dominated by a canvas… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Joel S. Davidi In my last post on the history of the first of Nisan as a Jewish new year I discussed the history of this now mostly forgotten holiday into the tenth century. Until this point, this… Continue Reading →

by contributing editor Yitzchak Schwartz Last month I once again attended the Manfred R. Lehmann Memorial Master Workshop in the History of the Hebrew Book at the University of Pennsylvania. This is my fifth year attending the workshop and my… Continue Reading →

by contributing editor Robby Koehler Writing in the late 1560s, humanist scholar Roger Ascham found little to praise in the schoolmasters of early modern England. In his educational treatise The Scholemaster, Asham portrays teachers as vicious, lazy, and arrogant. But… Continue Reading →

by guest contributor John Garcia Much of the pleasure of studying the economics of book publishing comes from the various minor personages who appear and disappear before the historian’s gaze. Sometimes patterns emerge from these fragmented discoveries, perhaps not enough… Continue Reading →

by Erin McGuirl The story of the revival of Harper’s Weekly, a magazine published from 1857 to 1916 and then 1974 to 1976, begins with William (Willie) Morris. As Editor-in-Chief of the Monthly from 1967 to 1971, Morris changed the… Continue Reading →

Like a literary manuscript in a publisher’s office, screenplays face rounds of revision and annotation in the motion picture studio. In the photograph above, someone holds a draft script for The Lady Eve, marked up with notes in several hands…. Continue Reading →