Tag

Botany

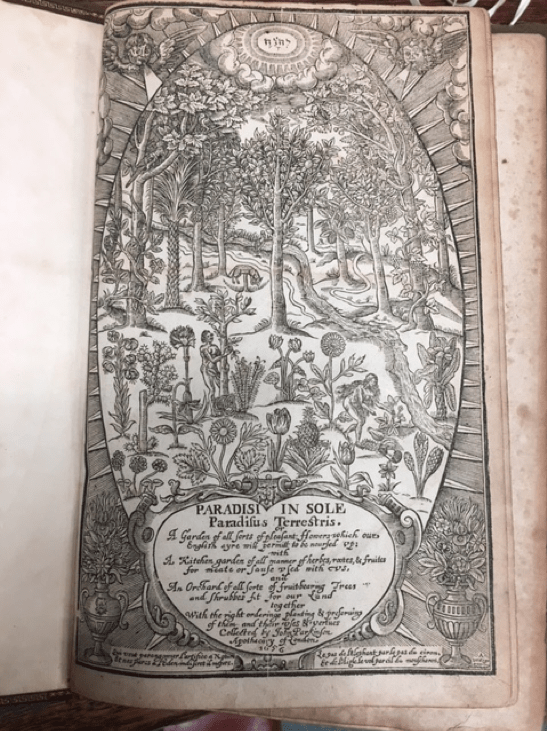

By Guest Contributor Molly Nebiolo The roots of contemporary botany have been traced back to the botanical systems laid out by Linnaeus in the eighteenth century. Yet going back in further in time reveals some of the key figures who… Continue Reading →

By contributing writer Joseph Satish V Only a month after India gained independence from the British in 1947, the Indian botanist Debabrata Chatterjee wrote of his hope that in the new India the Government will… effect among other things the… Continue Reading →