Tag Early Modern History

By guest contributor John Phipps February, 1639, and the festivities of the Roman carnival were approaching their apex. There had been processions and parades, public displays of civic and religious devotion—almost all bankrolled by the ruling Barberini family. The Barberini patriarch,… Continue Reading →

By contributing editor Luna Sarti This year several events will take place across the world to celebrate Leonardo da Vinci on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of his death. In Florence, where Leonardo lived and worked for several years,… Continue Reading →

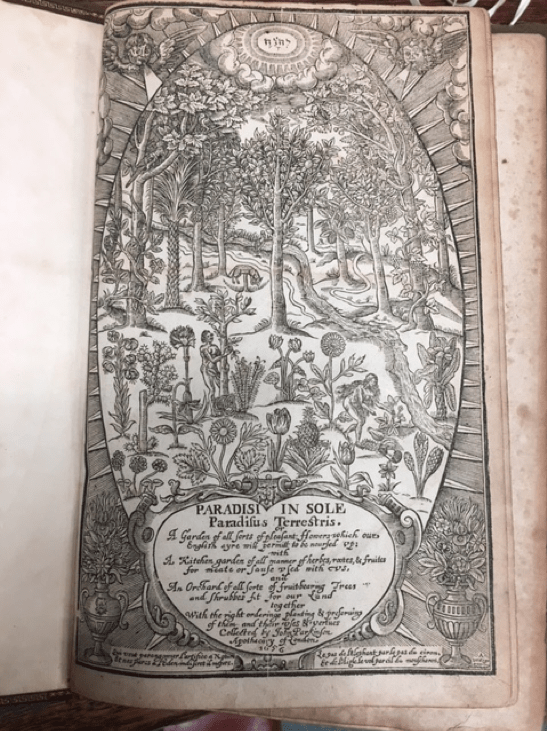

By Guest Contributor Molly Nebiolo The roots of contemporary botany have been traced back to the botanical systems laid out by Linnaeus in the eighteenth century. Yet going back in further in time reveals some of the key figures who… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Trish Ross For the full companion article, see this Winter’s edition of the Journal of the History of Ideas. “Human nature is the only science of man; and yet has been hitherto the most neglected.” Thus David Hume simultaneously… Continue Reading →

by guest contributor Bryan A. Banks In his 1865 La Révolution, Edgar Quinet addressed the question: Why did the republican experiments of 1792 and 1848 seem to turn to terror, empire, and tyranny? “The French, having been unable to accept… Continue Reading →

by contributing editor Robby Koehler Writing in the late 1560s, humanist scholar Roger Ascham found little to praise in the schoolmasters of early modern England. In his educational treatise The Scholemaster, Asham portrays teachers as vicious, lazy, and arrogant. But… Continue Reading →

by Contributing Editor Spencer J. Weinreich King Philip Came Over For Good Soup. Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species. Few mnemonics can be as ubiquitous as the monarch whose dining habits have helped generations of biology students remember the… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Adrian Young One can hardly imagine a more audacious ambit for a museum exhibit than that of the Staatlische Museen zu Berlin’s new show, Alchemy: the Great Art, now at the Kulturforum. In the curators’ words: “Alchemy… Continue Reading →

A Conversation with Benjamin Hoffmann, Assistant Professor of Early Modern French Studies at The Ohio State University and editor of a new edition of the Letters Written from the Banks of the Ohio by Claude-François-Adrien de Lezay-Marnésia (Pennsylvania State University… Continue Reading →