Tag History of Science

Ana Antić in discussion with Tom Furse about her review essay, “Psychiatry and Decolonization: Histories of Transcultural Psychiatry in the Twentieth Century,” published in the January 2024 issue of the journal.

Alec Israeli interviews Joyce E. Chaplin about her review essay considering recent books on the concept of the Anthropocene. (Part two of a two-part interview.)

Alec Israeli interviews Joyce E. Chaplin about her review essay considering recent books on the concept of the Anthropocene. (Part one of a two-part interview.)

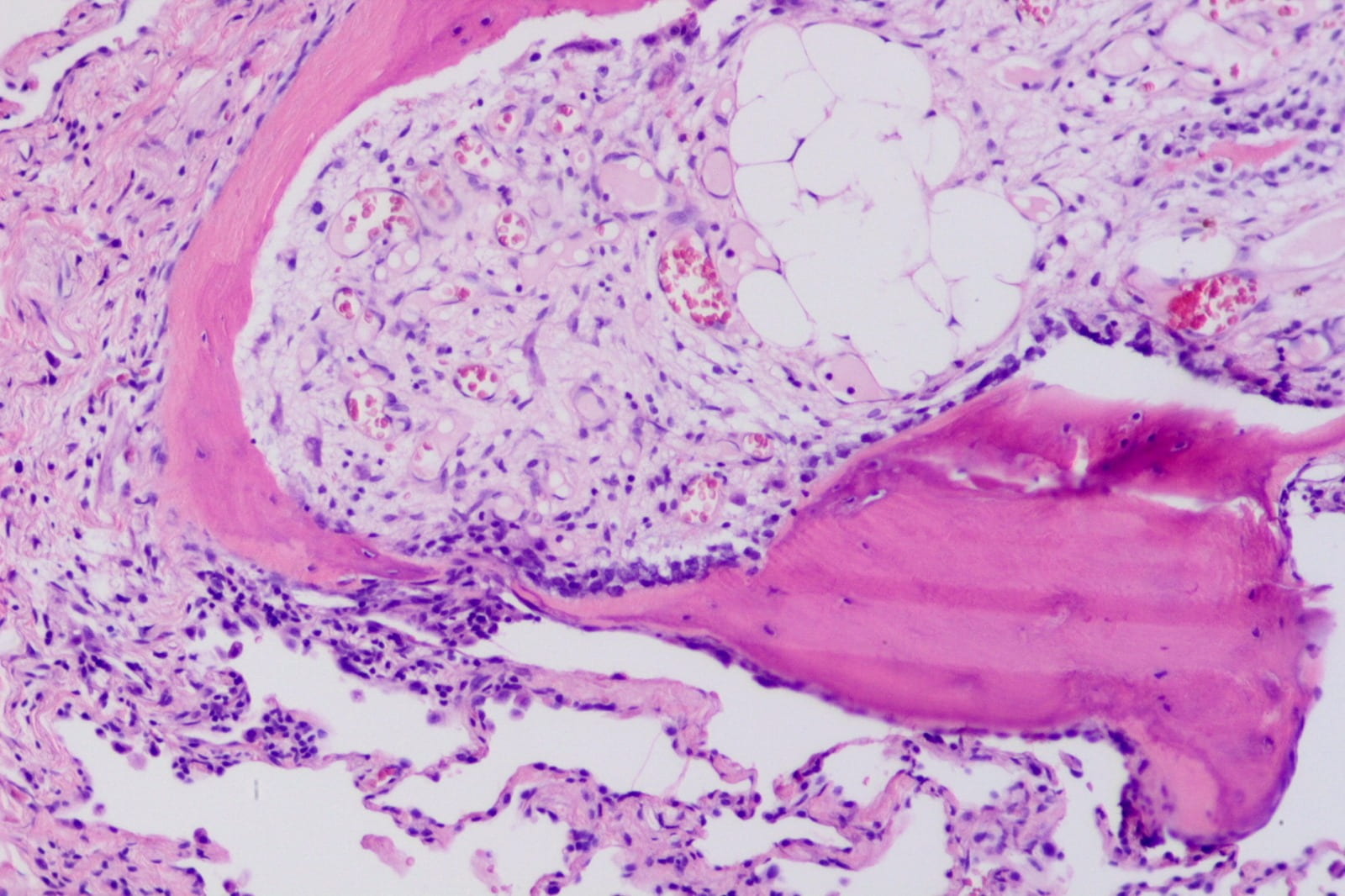

by guest contributor John DiMoia

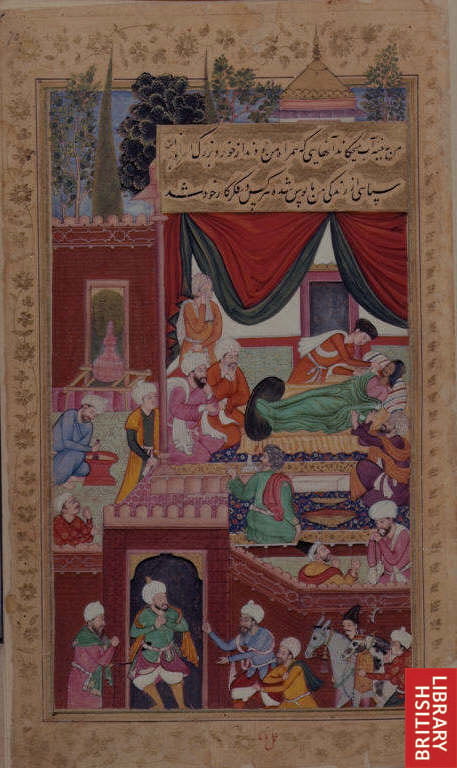

By guest contributor Dora Gao Celestial objects and events have appeared in the historical record for a myriad of reasons, serving as portents of either fortune or doom or asserting the divine authority of a ruler. The comet of 44… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Nicole Welk-Joerger In September 2016, Sadie Frericks, a Minnesota dairy farmer, recounted a moment in Hoard’s Dairyman when she and her husband noticed their heifers were trying to tell them something. She noted that the heifers “wouldn’t stop… Continue Reading →