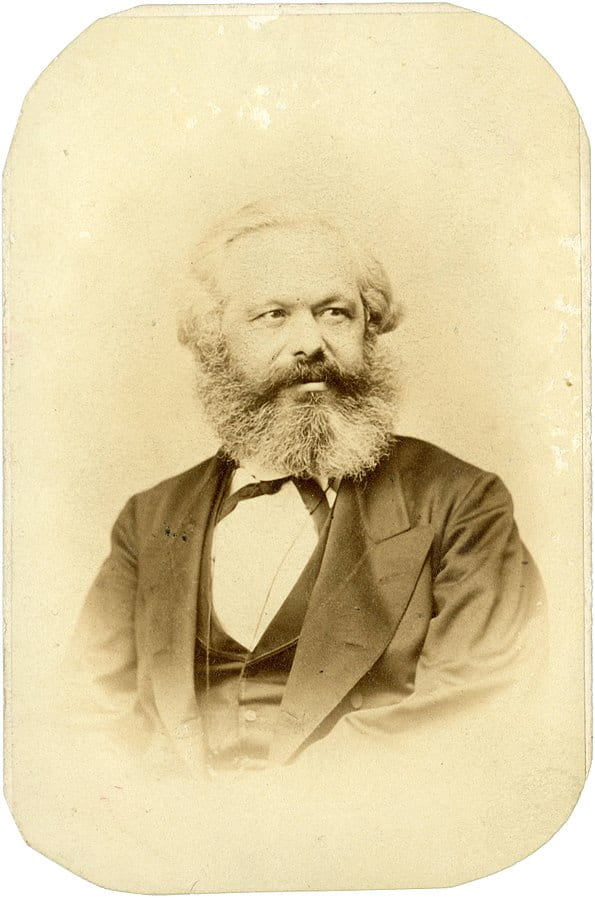

Tag Marxism

by Zac Endter and Jonas Knatz

By Contributing Writer Antoine Pageau-St-Hilaire In an interview with Günther Gaus in 1964, Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) recalls that she had started to read Immanuel Kant at the age of 14.[1] Evidently, this long and intense intellectual acquaintance with Kant played… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor, Jake Newcomb Last year, philosopher Graham Priest published an article in the Journal of the American Philosophical Association titled “Marxism and Buddhism: Not Such Strange Bedfellows.” In the article, Priest aimed to highlight the complementary elements of… Continue Reading →

by Eric Brandom Le congrès des ecrivains et artistes noirs took place in late September 1956, in Paris. Among the speakers was Aimé Césaire, and it is his intervention, “Culture and Colonization,” that is my focus here. This text has been the… Continue Reading →

by contributing editor Disha Karnad Jani In Enzo Traverso’s Left-Wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory, timing is everything. The author moves seamlessly between such subjects as Goodbye Lenin, Gustave Courbet’s The Trout, Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire, and the apparently missed connection… Continue Reading →

by guest contributor Jacob Hamburger When asked about his political orientation, for many years Axel Honneth would reply almost automatically, “I think I’m a socialist.” Yet as he recounted recently at Columbia University’s global center in Paris, each time he… Continue Reading →

by guest contributor Max Ridge “One of the most important things for radical critics to point to,” Marshall Berman writes in his first book, “is all the powerful feeling which the system tries to repress—in particular, every man’s sense of… Continue Reading →