Tag Music

by guest contributor Jake Newcomb

By guest contributor John Phipps February, 1639, and the festivities of the Roman carnival were approaching their apex. There had been processions and parades, public displays of civic and religious devotion—almost all bankrolled by the ruling Barberini family. The Barberini patriarch,… Continue Reading →

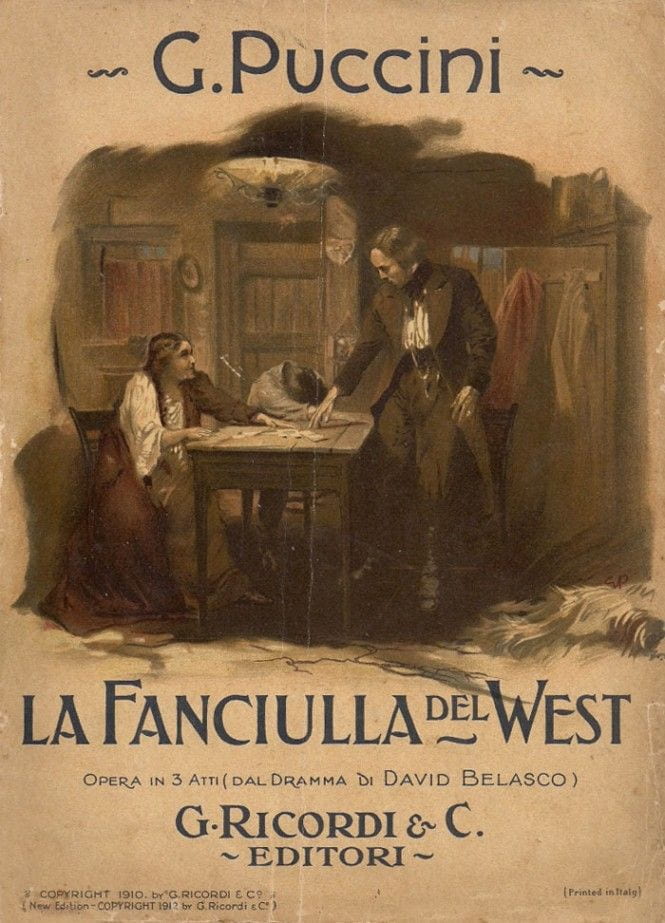

By Editor Spencer J. Weinreich “Whiskey per tutti!” “Benvenuto fra noi, Johnson di Sacramento!” “Una buona giornata per Wells Fargo!” (Puccini 11, 23, 50). La fanciulla del West (“The Girl of the West”), Giacomo Puccini’s opera set in the Wild… Continue Reading →

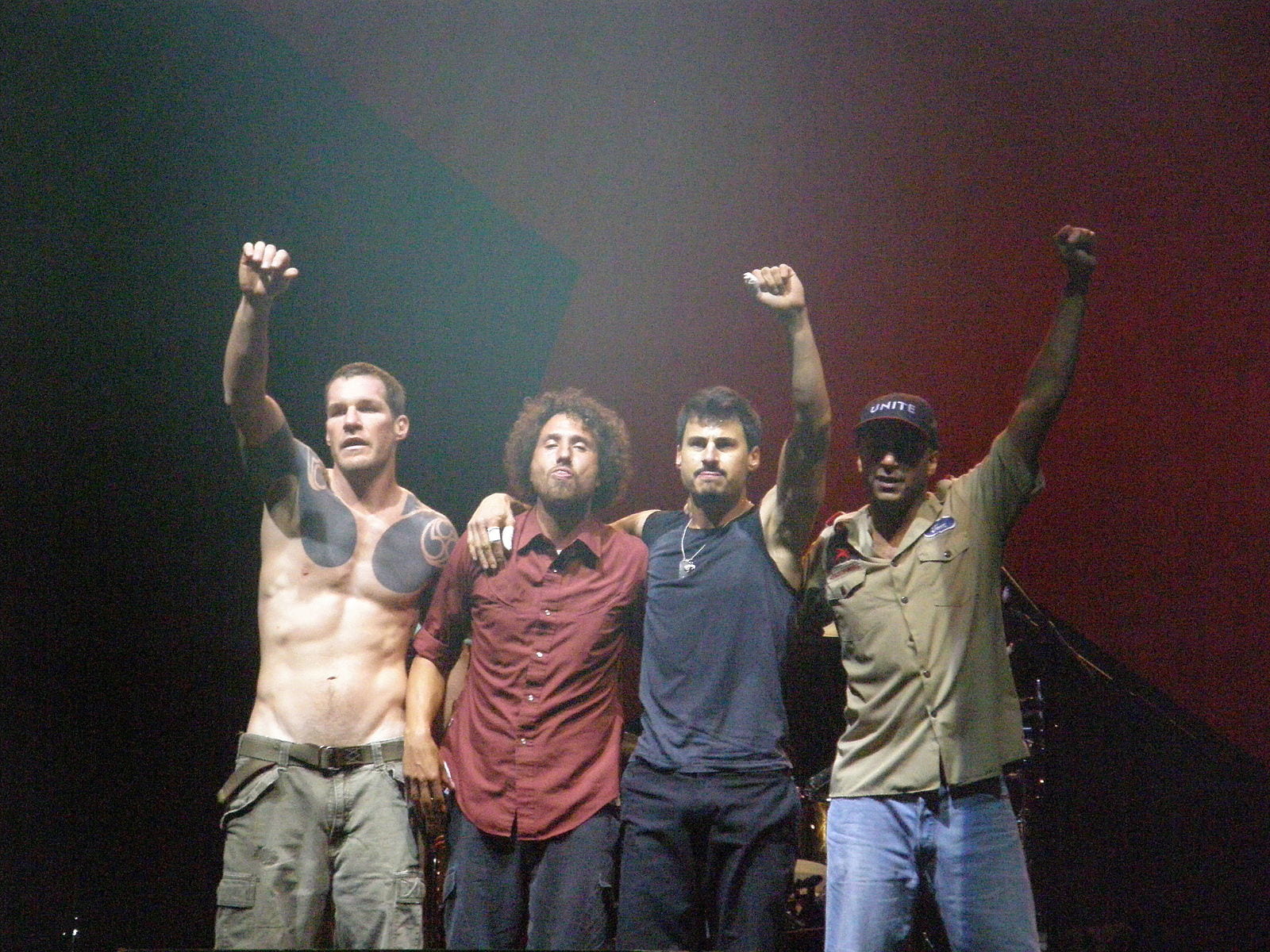

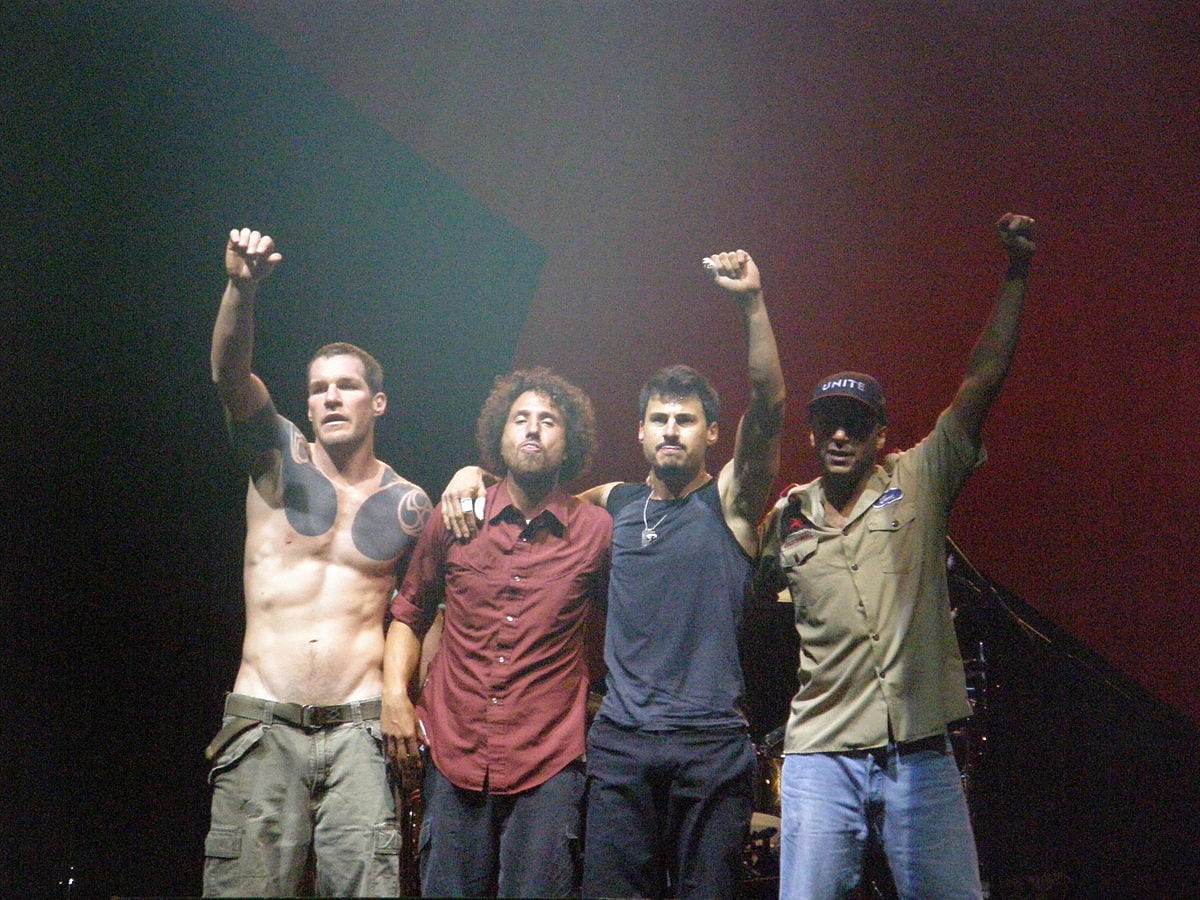

By guest contributor Jake Newcomb With the publication of Rhythm and Noise: An Aesthetics of Rock, philosopher Theodore Gracyk made the first breach into a modern ontology of rock music in 1996. Gracyk’s ontology postulated the idea that rock music… Continue Reading →

by guest contributor Monique Flores Ulysses Growing up as the child of a Mexican mother, when I heard Alejandro Fernández’s rendition of the popular corrido “Paso del norte” blasting out of our old speakers on a Saturday morning, I knew… Continue Reading →

by guest contributor Elad Uzan One of the ways in which the history of the Jewish people reveals itself is through music. The Torah, Writings [Ketuvim], and the Psalms contain over eight hundred references to the spiritual and religious usages… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Saraswathi Shukla The first periodical to successfully distribute musical scores to the French public was founded in 1762 and continued under different names by different editors through the French Revolution (Bruce Gustafson and David Fuller, A Catalogue… Continue Reading →