Tag Native Americans

By guest contributor Morgan L. Green Mid-twentieth-century anthropology was in crisis. Already influenced by World War II, anthropologists in the 1960s encountered a variety of dramatic changes. The scientific method and the pressure to be “objective” dominated as institutions like the National… Continue Reading →

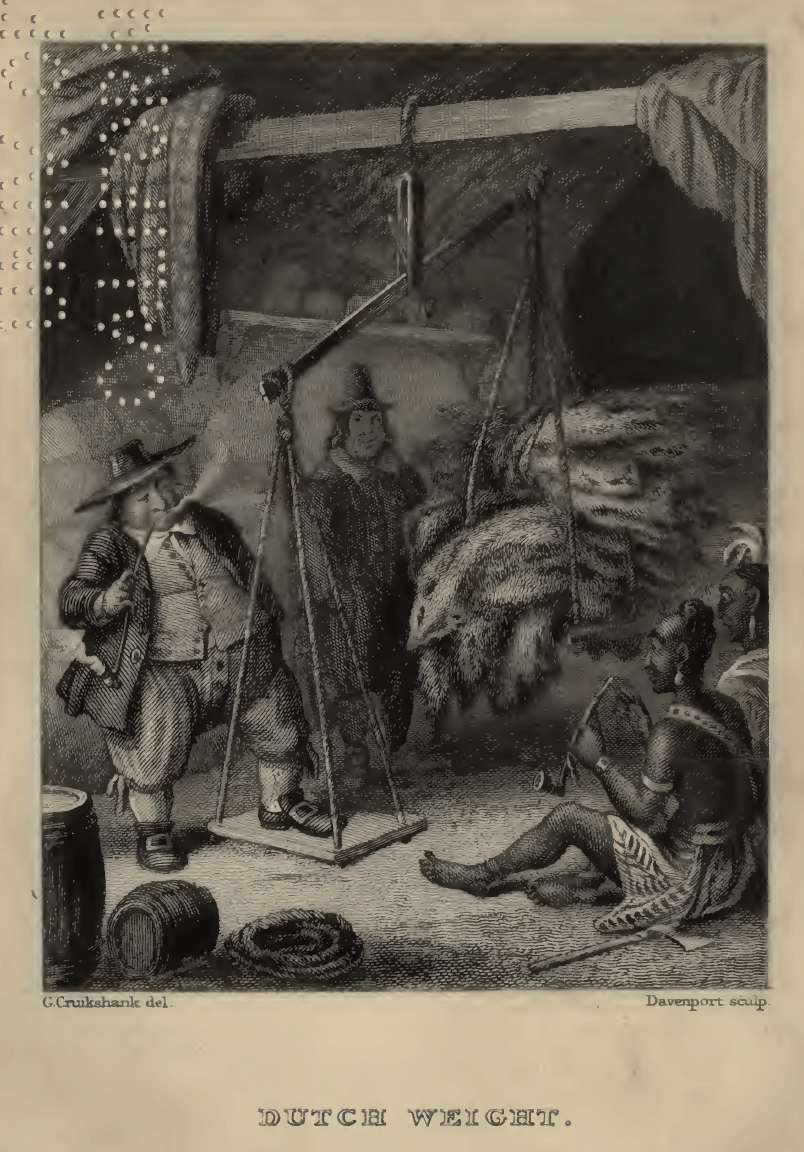

By Editor Derek Kane O’Leary Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan (1797-1880) was an unlikely candidate for the mammoth translation and historical project that he undertook at mid-life. A paradigmatic Atlantic creole, he had for decades crossed borders, learned new languages and skills,… Continue Reading →