Tag Philosophy

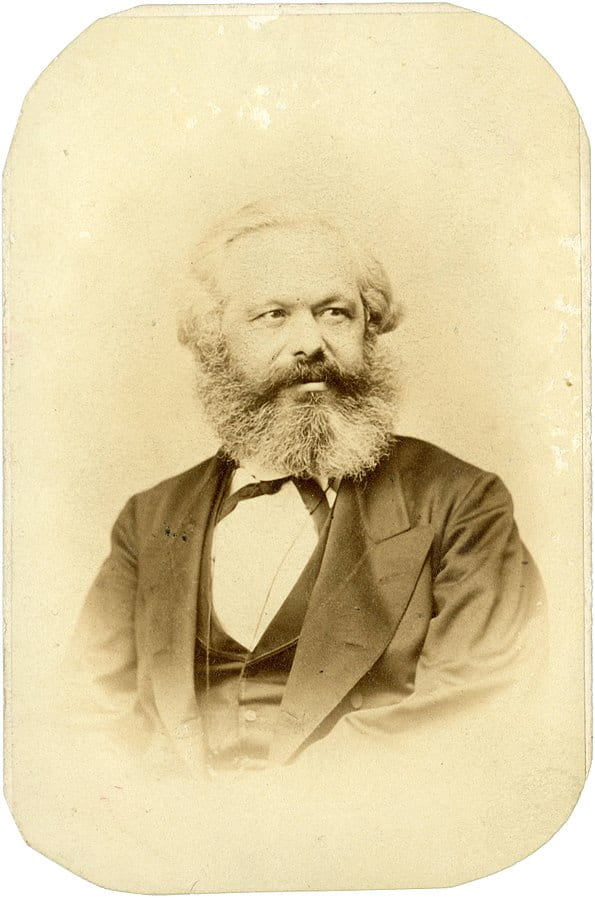

By guest contributor, Jake Newcomb Last year, philosopher Graham Priest published an article in the Journal of the American Philosophical Association titled “Marxism and Buddhism: Not Such Strange Bedfellows.” In the article, Priest aimed to highlight the complementary elements of… Continue Reading →

By contributing editor Andrew Hines How do human beings understand each other? This question has both a linguistic and a political dimension. Last month, as world leaders gathered at the Swiss town of Davos for the Annual Meeting of the World… Continue Reading →

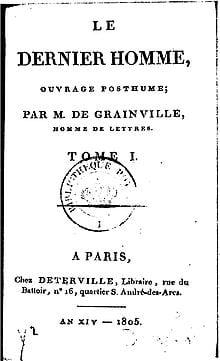

By guest contributor Audrey Borowski In his L’Oraison funèbre en l’honneur des citoyens tombés of August 10, 1792, the French writer and priest Cousin de Grainville preached a funeral oration full of revolutionary fervour for those killed during a recent insurrection…. Continue Reading →

Kristin While generally accustomed to questions more politically utilitarian than philosophical, my recent studies have led to a new forest of questions which I am having all too much fun exploring. These questions surround the concept of leadership. In a… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Christopher Porzenheim Even the smallest display of virtuous conduct immediately inspires us. Simultaneously we: admire the deed, desire to imitate it, and seek to emulate the character of the doer. […] Excellence is a practical stimulus. As… Continue Reading →

By guest contributor Niklas Plaetzer Walter Benjamin never left Europe, yet his writings have had a remarkable impact on critical thought around the globe. As Edward Said suggested, the dislocation of an idea in time and space can never leave its… Continue Reading →

by guest contributor Jeffrey A. Barash