by guest contributor Zachary Levine

Wilhelm Reich, later in life (Wikimedia Commons)

What should we do when brilliant thinkers push their ideas in strange directions? Should we try to interpret their later work in the context of their earlier work, or vice versa? Should we reject their later work but embrace their earlier work, as JS Mill did with Auguste Comte? By and large, this latter approach has been applied to Wilhelm Reich. His early political writings,including “Dialectical Materialism and Psychoanalysis” (1929) and The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933), have been of interest to political dissidents and intellectual historians, while Character Analysis (1933) is still read by psychoanalysts. By contrast, Reich’s theory of the “orgone,” a specific, measurable life energy that formed the centerpiece of his research from the late 1930’s until his death in 1957, has been written off as an especially bizarre form of vitalism by all three groups. While Reich argued that orgone energy could be detected and harnessed in cells and living beings, few other scientists agreed that it existed at all. Deservedly or not, Reich’s orgonomic work earned him a reputation for unfounded medical treatments and amateurish research that has largely precluded serious historical interest. (Two notable recent exceptions are Petteri Pietikainen’s Alchemists of Human Nature and James Strick’s Wilhelm Reich, Biologist.)

For his part, Reich later in life argued that a “red thread” ran through all of his work: “the theme of the bio-energetic function of excitability and motility of living substance” (as cited in Chester Raphael’s forward to Early Writings, Volume 1). In other words, the orgone can be found at the core of his earlier studies, though he was not initially aware of the true nature of the object of his own research; scratch the surface of the character analyst and you find an emerging orgonomic scientist. If he saw bio-energy as the red thread of his work, he was willing to jettison his social theories, or at least relegate them to the periphery of his worldview. By the early 1940’s, he claimed to have entirely abandoned political thought, having been hurt and offended by his 1933 expulsion from the Communist Party and quickly becoming disillusioned by the USSR’s sexual conservatism and apparent truce with fascism. As he ceased to see himself as a political thinker, he came to emphasize the role of bio-energetic function in his earlier writings. By the end of his life, he understood the most crucial features of his early work to be those that he emphasized in his orgone research program.

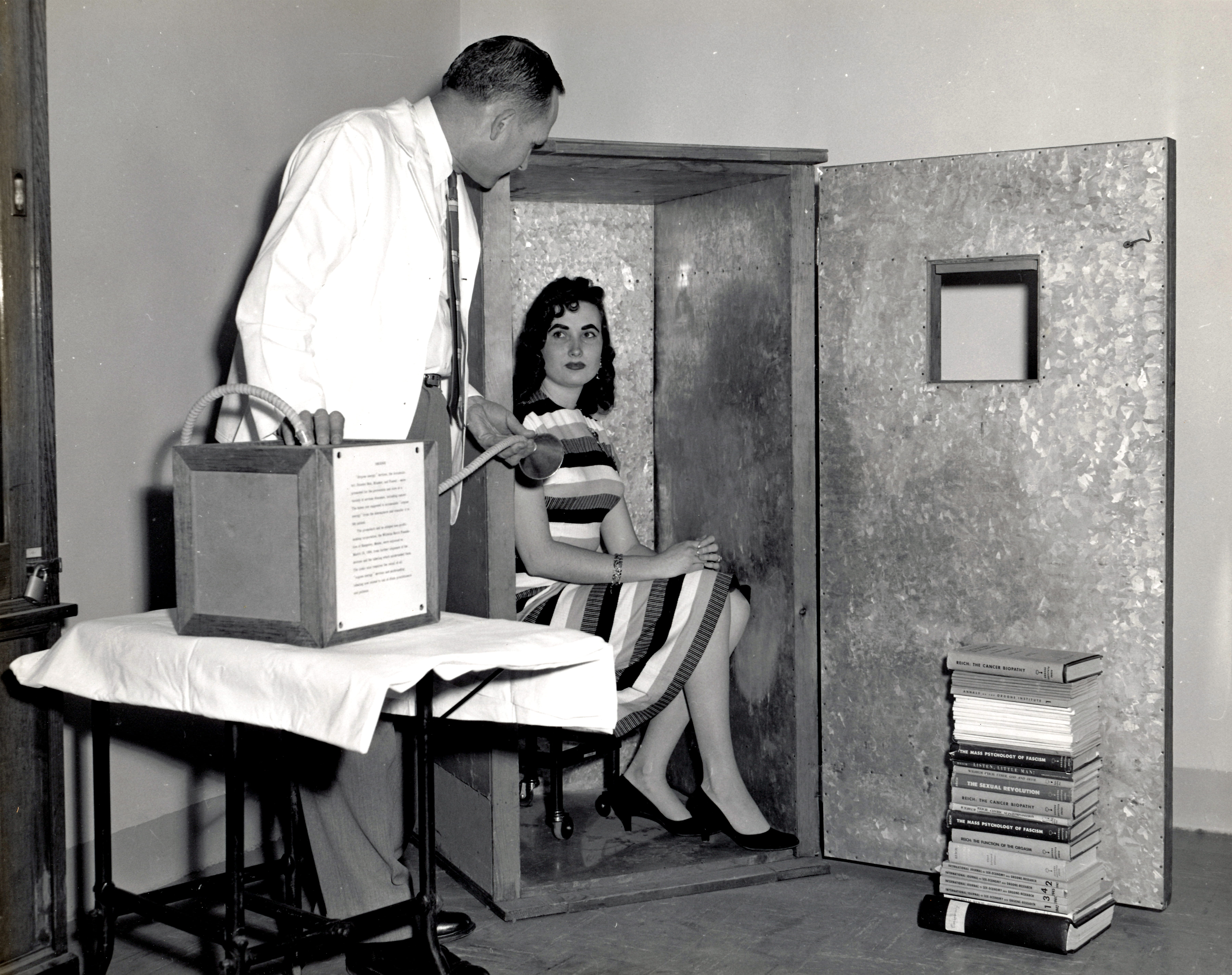

One of Reich’s “Orgone Accumulators,” which he believed could have healing properties (Wikimedia Commons)

Still, in spite of Reich’s self-assessment, political and social thought remained key components of his intellectual framework. As Reich became disillusioned with the USSR, he began to develop a new political theory: “Work-Democracy.” In a set of chapters that were added to English translation of the 3rd edition of The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1946) based on pamphlets written from 1937 through the early 1940’s, Reich described the nature of Work-Democracy: “Work-Democracy is the natural process of love, work, and knowledge that governed, governs and will continue to govern economy and man’s social and cultural life as long as there has been, is a, and will be a society.” Reich argued that Work-Democracy was not a political or ideological system, but it seems clear that it was designed to be a political system built on labor organization. Though Work-Democracy is the system in which laborers naturally self-organize, Reich argued for a future political order based on Work-Democratic principles: “For the first time in the history of sociology, a possible future regulation of human society is derived not from ideologies or conditions that must be created, but from natural processes that have been present and have been developing from the very beginning.”

Reich’s biological and political theories never ceased to be interconnected. Just as Reich’s psychoanalytic theories informed his earlier sex-political and Marxist social theories, Work-Democracy was built on his new research platform. As he argued, it was from the “point of view of bio-sociology” that “there could be no clear-cut division between one class and another.” He also claimed that Work-Democracy produced the conditions for “objective and rational interlacing of the branches of work.” The intersections between biology and physics necessary for orgonomic research would develop most easily in a work-democratic society. The idea that orgone research would be a tool in political struggles for the future of humankind is also built into Reich’s later published work. In Reich’s 1949 Ether, God and Devil, he described his research as “not a question of philosophies, but of practical, decisive tools in the formation of human existence; it is a question of the choice between good and bad tools in the reconstruction and reorganization of humanity.”

Reich’s FBI file further belies his claim to have abandoned politics. Reich had been detained by the FBI for several weeks in 1941-1942, but after a cursory investigation in 1945, the FBI determined that Reich was no longer an active Communist. Consequently, after 1945, the file consists almost entirely of attempts by Reich and his followers to contact the FBI about the political importance of his work. In a 1953 letter to John J Finn, Reich argued that the US was in grave danger from “the inner emotional and characterological helplessness of people at large who, through their passivity and neuroses are unwillingly and unknowingly carrying political evil to power.” Reich’s followers made similar claims. In a 1949 FBI interview with Myron Sharaf, Sharaf reported Reich’s skepticism about erstwhile fellow researcher William Washington to the FBI “because the directors of the Orgone Institute Research Laboratory felt that it would jeopardize the welfare of the United States for the information and knowledge that Washington has on Orgone Energy, specifically, its reaction to the Geiger-Muller Counter, to fall into the Russian or foreign agent’s hands.” Communism and scientific criticisms of Reich were seen as interrelated. Sharaf complained that “Dr. Frederick Werthan [sic], in [The New Republic], on December 2, 1946, was slanderous and critical in reviewing the work in Orgone research; and that the Communists and fellow travelers have been very critical to Dr. Reich since 1939.” For Reich and his followers, Reich’s scientific research into the orgone could not be separated from the challenge it presented to the Communist party and the USSR. In fact, Reich’s views fit nicely into the anti-totalitarian rhetoric of the postwar years; the FBI file is rife with references by Reich and his followers to “red fascists” and “red imperialists.”

“Orgonon,” in Rangeley, Maine, where Reich lived and worked for the last several years of his life (Wikimedia Commons)

Reich’s political and scientific ideas were intermingled, and despite the evaluations proffered by both Reich’s supporters and his detractors, this connection established the ideological framework that motivated all of his work. Reich was derided and persecuted throughout his life. To the best of my knowledge, he holds the dubious distinction of being the only person to have been targeted by the Communist Party, the Nazi party, the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA), and the Food and Drug Administration. When Reich was disappointed by his expulsions from the Communist Party and IPA, he slowly stopped trying to understand the connections between his ideas and those of Freud, or the resonance between his vision of the state and the USSR. And yet, he never abandoned his attempt to reconcile therapeutic or scientific practice and political engagement. In my view, he was a consistent scientific utopian, protecting the overall shape of his ideological framework by modifying its pieces as the political and scientific world disappointed him.

Zachary Levine is a third-year doctoral student at Columbia University. His research involves the role of the case study in the brain and mind sciences, intersections between intellectual history and the history of science, the history of psychoanalysis, and the history of neurology and psychiatry in France.

July 28, 2016 at 10:18 am

Reblogged this on Deterritorial Investigations Unit.

January 2, 2018 at 10:00 am

Looks to me that you are a serious student with an open mind. Keep going!