by guest contributor Anna Toledano

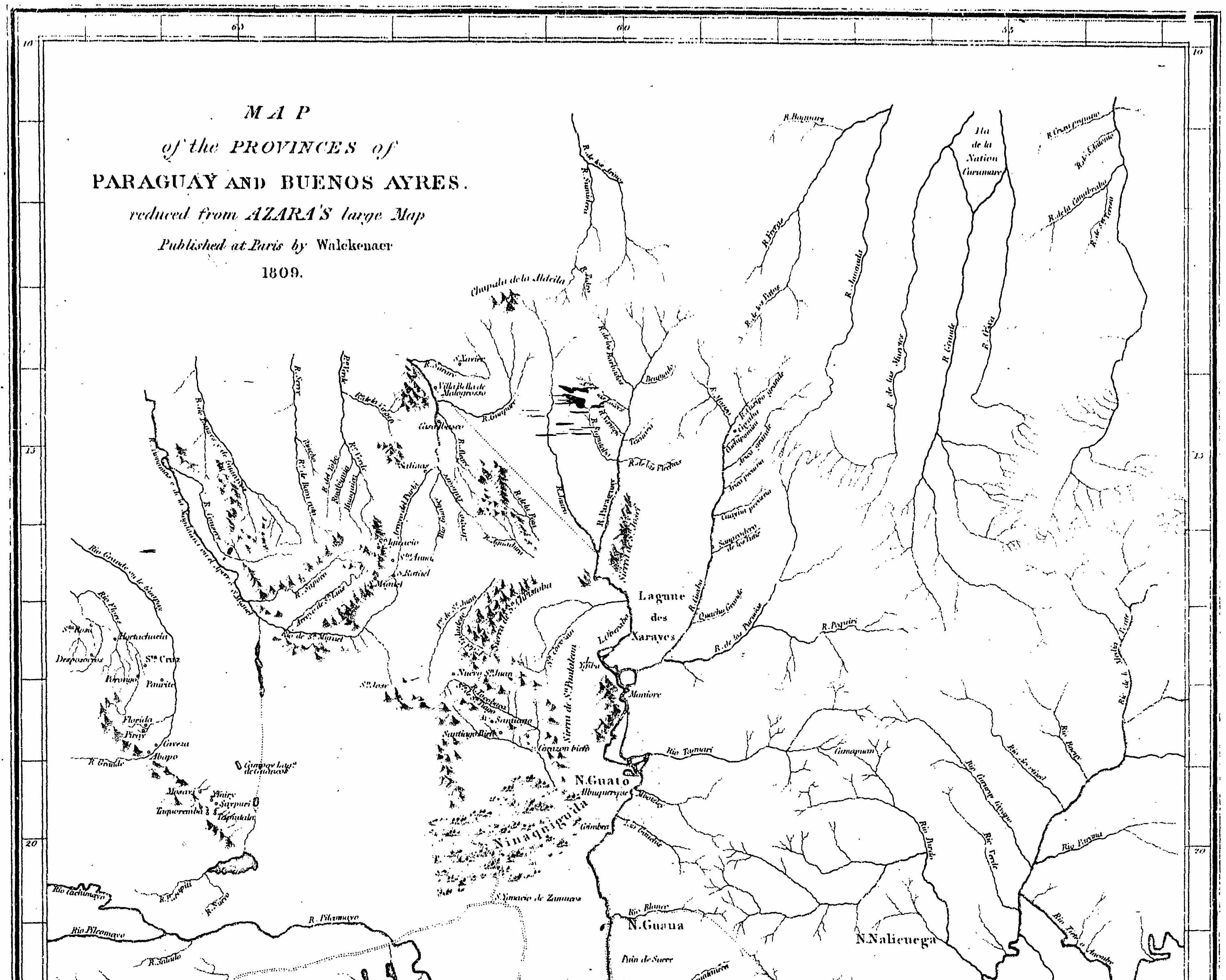

Decades before Darwin set out on his voyage on the H.M.S. Beagle, Félix de Azara (1742–1821) observed many of the same species of animals and plants that the famed Englishman would see during his journey. Charged by the Spanish army with the task of drawing maps of the Spanish and Portuguese territories in the Río de la Plata region of what is now Paraguay and Brazil, Azara arrived in South America on March 12, 1781 and remained in the region for twenty years. The expedition proved long and monotonous, providing the curious, assiduous Azara with much time to observe the wildlife and peoples near the Río de la Plata.

During his time in South America, Azara amassed a significant collection of natural history objects. In 1788, he sent an extensive set of birds for study to the Royal Cabinet of Natural Sciences—what is now the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid—by way of José Moñino y Redondo, the Conde de Floridablanca (1728–1808), who was chief minister in charge of Spain’s foreign policy. Azara had preserved the birds using aguardiente, a strong grain alcohol. In a letter dated September 13 of the same year to Eugenio Izquierdo de Rivera y Lazaún, the director of the Royal Cabinet, Azara indicated that he hoped to “gather all of the species of birds, describe them and send them” to Spain (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales and Calatayud Arinero 1984, 198). The box later arrived at the Cabinet with 107 specimens inside.

The personnel in Madrid did not view the specimens with as much enthusiasm as Azara did. The arduous journey—as well as the alcoholic aguardiente—had been unkind to the “avecillas.” Vice director of the Cabinet, José Clavijo Fajardo, sent his thanks to Azara via the Conde de Floridablanca, but only for drafts of Azara’s Remarks on the Natural History of the Birds of Paraguay and Rio de la Plata and not for the ill-preserved birds. The naturalists at the museum saw them as worthless for taxidermy and study. Tragically, the Cabinet could not accommodate the unidentified, aboriginally-named birds in Azara’s collection (Figueroa 2011). Since neither Buffon nor Linnaeus had referenced any of the species that Azara identified, Clavijo considered them uninteresting and disposed of them (Calatayud Arinero 2009, 90-91).[1]

While this anecdote serves as an example of the capriciousness of what survives the sands of time and what does not in terms of objects of natural history, it also illustrates the attitude at the Spanish institution—and among educated Spaniards themselves—toward Azara during his lifetime. The Cabinet rejected Azara’s specimens because it operated within a different knowledge paradigm that did not value the same objects and methods of science that Azara, separated by an ocean, had developed for himself. Azara was not Bernard Shaw’s itinerant British sailors in the South Pacific, for whom “the problem of observing and interpreting what they saw…was…a simpler matter…than for the exiles and missionaries who followed them” and began this new, foreign way of life. Azara was not enjoying merely “extended, if dangerous, holiday;” he had, in fact, a “deep emotional break…[from] a homeland never, perhaps, to be seen again” (Shaw 1950, 85).

Azara’s lack of professional training as a naturalist may have played a role: although he was well-versed in mathematics and the physical sciences, his practical biological knowledge was self-taught. Azara maintained that his observations of animals as they lived in the wild prevented him from drawing the same mistaken conclusions as European naturalists. In his introduction to his treatise on quadrupeds, Azara stressed that he

[put] all my care to tell the truth without exaggerating anything, and to know and express the characters of the animals whose descriptions I made in their presence. Because of this I have been less at risk to fall into the errors that those who have not been able to observe them alive have not been able to avoid; those who have beheld them emaciated, hairless and dirty in cages and chains; and those who have sought them in cabinets: where, in spite of care, the injury of time must have altered the colors heavily, changing the black into brown, etc.: and no skin, nor the best-prepared skeleton, gives the exact idea of the shapes and sizes (Azara 1802, i-ii).

He lambasted armchair scientists who made all of their discoveries not in the field but using stuffed skins and bones in the museum (Cowie 2011, 5).

Azara’s professional contemporaries at the Royal Cabinet did not refuse his work in its entirety. Azara enjoyed some success from his publications in his home country as well as other European nations. Yet his books were not as effective at describing the birds as were the birds themselves. Different forms of knowledge held value over others.

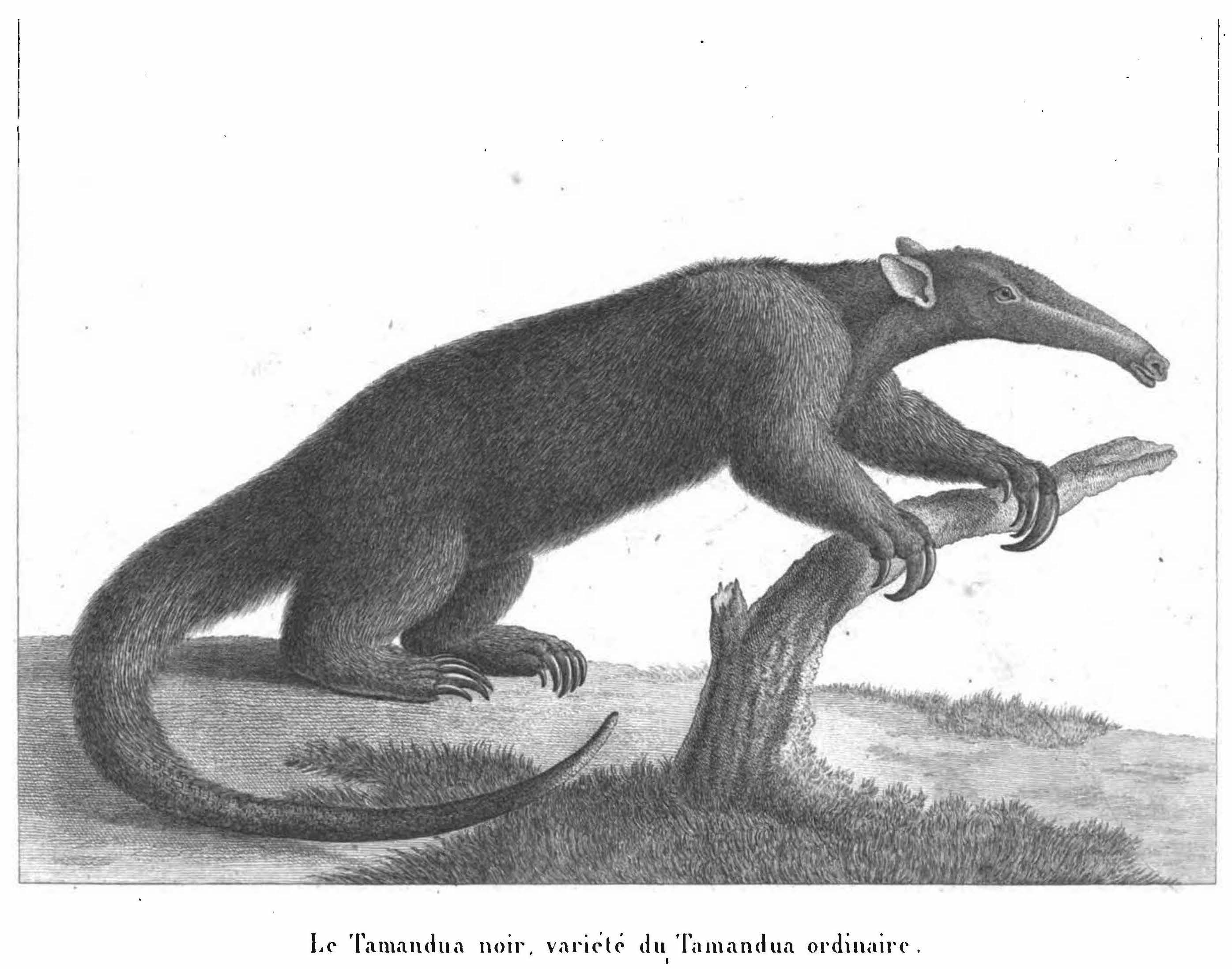

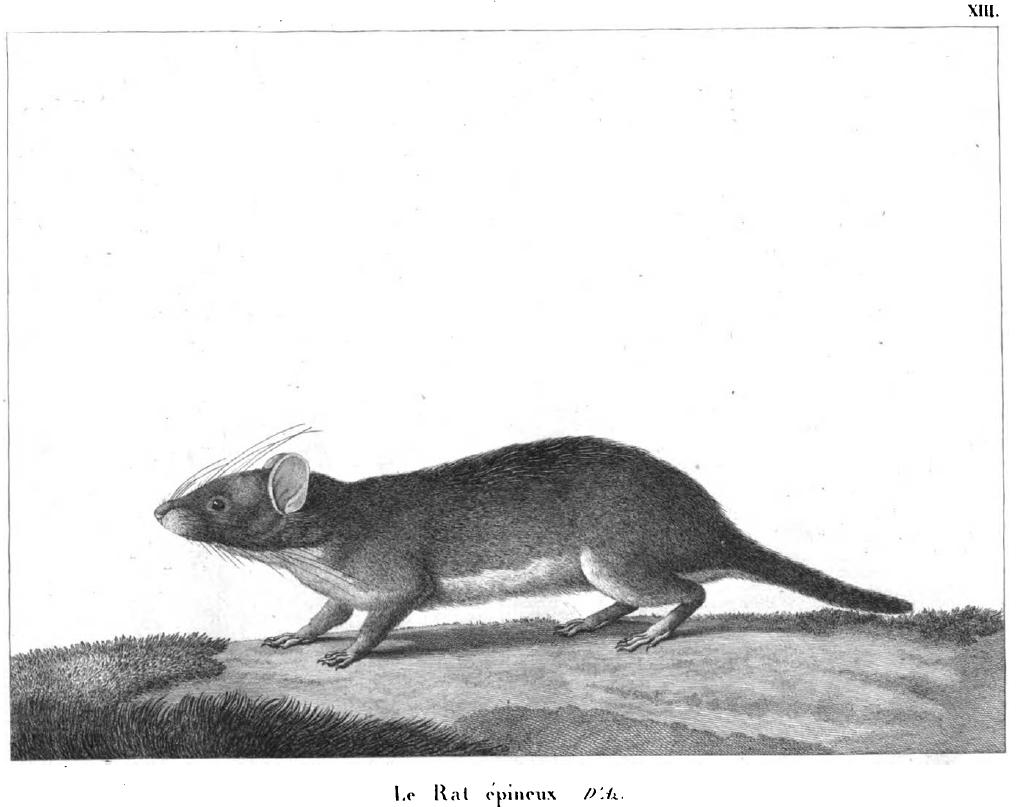

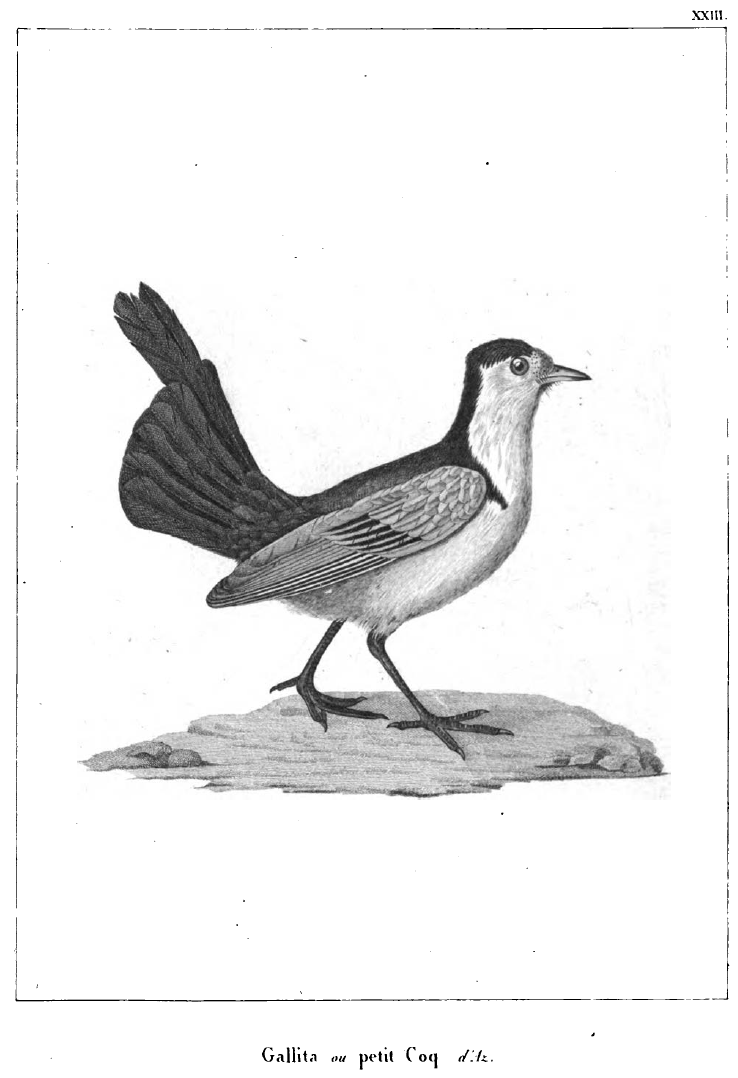

Through illustrations was one way that Azara could command an audience. As Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison argue in their work on objectivity, “Whatever the amount and avowed function of the text in an atlas, which varies from long and essential to nonexistent and despised, the illustrations command center stage” (Daston & Galison 1992, 85). Azara incorporated drawings of the bird and animal species he discussed in his numerous multi-volume tomes on the flora, fauna and ecology of the South American region where he lived. His best-known works include the aforementioned Remarks on the Natural History of the Birds of Paraguay and Rio de la Plata and Remarks on the Natural History of the Quadrupeds of Paraguay and Rio de la Plata, for which he tried his hand at illustration as well, despite his admitted lack of skill (Azara 1802, iv). For the French edition, Azara hired an illustrator, but he drew from the specimens in the Paris Museum rather than from life (Cowie 2011, 135). Azara could not have it all: he had to choose between his crude drawings from the field or professional depictions of dead museum specimens. Explore the pictures below to make your own assessment. What explanatory power do these images hold?

The black anteater, one of the two varieties that Azara studied, as illustrated in the French edition of his Voyages. Azara commissioned these illustrations from specimens that he identified in the museum in Paris as correctly corresponding to those in his notes from South America (Azara 1850, 4). He corrected a falsely held notion in Europe that every anteater was female and that their proboscides substituted for something more phallic in the act (Azara 1802, 65).

Azara was the first to identify a significant number of animal and plant species during his time near Río de la Plata, including this species of rat. Modern evolutionary biologists continue to examine his own taxonomic and naming practices as well, since he classified many mammals and birds using hybrid binomials that scientists still employ today, despite his ignorance of proper practice in Linnaean nomenclature. One set of researchers, hailing from institutions such as the American Museum of Natural History as well as the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid, updated Azara’s taxonomic description of varieties of opossums in order to conform with present-day research. They state that Azara’s “descriptions are detailed enough to permit unambiguous identifications of many species” (Voss et al. 2009, 406-407).

Forty pages of descriptions and notes accompanied the birds that Azara sent to the Royal Cabinet, which totaled 84 specimens of 61 different species. He listed the birds’ descriptive, hybrid indigenous-and-Spanish names such as the “Tugüay-machete” and the “Yby̆y̆aù sociable” (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales and Calatayud Arinero 1984, 197). In a detailed four-columned list, he also included the sex and assessments of the condition of the individual specimens (Figueroa 2011).

Azara did adhere to his original mission, lest one forget what that was. He made some efforts to draw maps of the region, such as the snippet of this comprehensive one included in the beginning of the 1838 English edition of his treatise on quadrupeds. The act of surveying proved extremely difficult not just for him but also for the Spanish representatives sent to other South American regions. Historian of Latin America Tamar Herzog describes the hurdles that they encountered, such as

treaties [that] often mentioned rivers, settlements, and mountains that never existed or were not located where the parties had imagined. Others had a different name in Spanish and Portuguese. Because the territory was not only huge but also unknown, experts[’]…work degenerat[ed] into endless debates regarding where rivers flowed and where mountains were located.

Just as with the sixteenth-century treaty of Tordesillas, Herzog writes, “these experts thus failed to reach concord on how a theoretical, imaginary line described in a European document would become a concrete, material reality in the Americas” (Herzog 2015, 32).

A work featuring Félix de Azara appears in yet another Spanish institution, but it is perhaps neither in the expected medium nor in the expected museum. In 1805, the Spanish artist Francisco Goya painted Azara’s portrait, which now hangs in the Goya Museum in Zaragoza, Spain. Azara wears his military regalia, replete with sword, cane and well-pressed uniform. Yet, his intellectual pursuits also figure into the symbolism of the scene. He holds in his right hand a paper, indicating he is a learned man. Most wonderfully, behind him is a veritable cabinet of curiosities. Taxidermied felines grace the lowest shelf while his beloved birds overflow on the others, tucked away for study when necessary.

Anna Toledano is pursuing a PhD in history of science at Stanford University. A museum professional by training, her research focuses on natural history collecting in early modern Spain. Follow her on Twitter at @annatoledano.

July 13, 2016 at 5:58 am

Brilliant brilliant resource, really hard to find such a material online. An immense thank you for the time invested in this article, brilliant brilliant !

July 15, 2016 at 11:09 am

Thank you for your kind words! I’m so glad to have been able share Azara’s story with a wider audience here.

July 15, 2016 at 11:11 am

Thank you for your kind words! I’m glad to have been able to share Azara’s story with a wider audience here.