by Shuvatri Dasgupta and Senjuti Jash

In South Asian historiography myths, local legends, chronicles, and folklores function as primary sources for the writing of “history,” or itihasa, as Romila Thapar has illustrated. Within the broad genre of fiction, historians have traditionally used social novels or short stories, and have overlooked popular fiction dealing with ghosts and spirits. Residing in an alternative society to that of the anthropocentric one, in fictionalized narratives and anecdotes, ghosts represented the “other” of the Bengali “self” during the nineteenth century. In this piece, we explore ghost stories as texts which can inform a bottom-up approach to histories of the nineteenth-century Bengali mind.

Why did the spectral community find popularity in the fictional realm of the Bengali mind during the nineteenth century? The primary reason behind this are the cholera, malaria, and plague epidemics which wreaked havoc in villages and cities, wiping out more than half of the population in Bengal during the early nineteenth century. From 1839 onwards, these epidemics spread from Bengal to other parts of India, as John Hays has shown. As the number of discarded and diseased corpses increased, ghosts found a place in the Bengali psyche facing the realities of death in their everyday worlds. In this scenario, the discourses of science and medicine produced a space at the intersections of “rationality” and “spirituality,” and engendered these accounts, which were transmitted both orally and in print.

The category of “ghost” remained fluid: in some stories they were seen, while in some their presence was only felt. In the fictional narratives, an environment of phantasm was created with omens like black cats, moonlight, and veiled silhouettes. The spaces of deserted houses and dilapidated bungalows acquired a metaphorical organic significance in these discourses. In a Bengali proverb from Comilla (Bangladesh), roughly translated as “ghosts inhabit a broken-down house,” the house signified the human body crumbling under various incurable ailments, which attracted ghosts to make the ailing human one of their own.

Local legends from Rangpur (Bangladesh) dating back to the nineteenth century described the habitats of different types of ghosts in various kinds of trees, namely Palmyra, Tamarind, and Madar. Ghosts also inhabited trees like Banyan, Sand Paper, Acacia, and Bengal Quince. The allocation of habitats in the spectral world mirrored anthropocentric normativities associated with gender roles. For example, the male Brahmin ghost, namely the Brahmadaitya, usually inhabited tall evergreen trees like Aegle Marmelos, Peepul, and Magnolia, maintaining his social superiority over others even after death. Female ghosts inhabited smaller shorter bushes and shrubs like the Streblus Asper and others. The Brahmadaitya’s habitat in comparison with the female ghosts’ habitats illustrated not only his primacy on the social ladder, but also the gender normativities permeating into the “other” world from the human world.

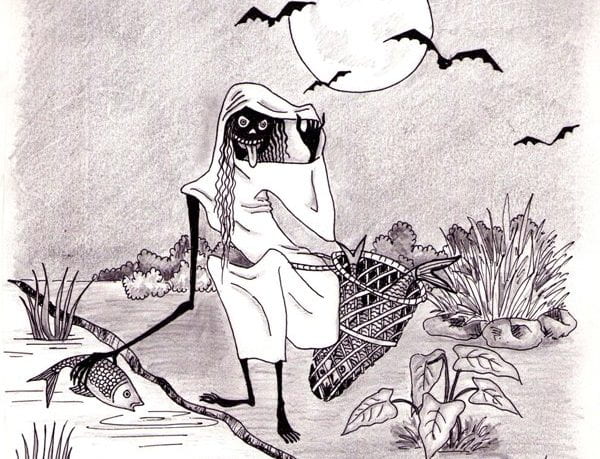

In a famous anthology of tales compiled in the early twentieth century titled Thakurmar Jhuli (Grandma’s Bag of Tales), the narrator was an old woman entertaining her grandchildren, with a barely-disguised didactic tone. These tales reflected an element of moral speculation attached to the gender roles of the ghosts. Female ghosts like the widowed Petni were portrayed as attracted to fish, given the nineteenth century Indian tradition of widows living an ascetic life with dietary regulations. The construction of this ghostly image functioned on two levels: the reflection of the past married life on the widowed “self” of the narrator, and the articulation of these suppressed desires through the representations of the “other” widowed ghost. This dual self-projection of the narrator served a greater purpose, as it participated in the ongoing discourse about the issues of sati and widow remarriage, contributing to larger debates about the rights and privileges of women in nineteenth-century Bengali society.

With the colonial government’s criminalization of sati and legalization of widow remarriage, as Lata Mani has shown in her seminal article “Contentious Traditions,” women became sites of conflict for redefining “tradition.” There was a clear colonial preoccupation with the state of women as a benchmark for appraising civilizational standards. For the colonial masters, the injustice and oppression meted out to Indian women in the form of sati became a corroboration of “British modernity” and a moral platform on which their “civilizing” endeavor could be justified. The “feminine” hence provided a space for renegotiating what was “Indian” and what was “Western.” The female ghosts were clearly no different. While Indian women gradually unified over shared demands for various rights, the ghostly women from the other world expressed their solidarities for these reforms through the figure of Petni indulging in fish.

In these fictionalized narratives, living women—especially the ones who were pregnant or had long lustrous hair—were portrayed as more susceptible to ghostly encounters. Also, medical conditions such as seizures, epilepsy, multiple personality disorders, and schizophrenia in women were diagnosed by the quacks as being possessed or inhabited by evil or unholy spirits. These women then were subjected to the autonomy of the exorcists. They were sexually exploited under the pretext of exorcism and were sometimes even forced to marry the exorcist as a favor in return. Since most of the oral tales were produced by female narrators, they served as a space to articulate and in turn resist the threats women faced from the community of exorcists and failed to overcome in the human worlds.

The influence of colonial race theories was also clearly detectable in the world of horror fiction, as they emerged as a significant premise for British epistemic exercises. Significant segments of British and European intellectuals, even during the age of the Scottish Enlightenment, considered Indians to be closer to black Africans, or black Malays, than they were to white “Caucasians.” As Swarupa Gupta comments, there was “selective adaptation, internalisation and re-articulation” of the basic tenets of imperial race theory, interwoven with prevalent conceptions of Hindu caste hierarchy within the Indian milieu, after the Census of 1871 (Notions of Nationhood, 112-13). While ordinary ghosts, both male and female, were described as dark-skinned, the Brahmin male ghost was portrayed as fair-skinned, tall, exhibiting saint-like feet, and wearing sandalwood sandals. On one hand, widowed Petni was depicted as a very dark-skinned figure; on the other, the ghost of the Muslim man, known as Mamdo, was also depicted with similar adjectives. Additionally, he wore a skullcap and featured an unkempt beard. The image of the Islamic ghost succumbed to colonial stereotypes, resembled its human image and position in society.

Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s short story “Oshoriri” tells how a Bengali middle-class man from Calcutta mistook his low-caste dark-skinned Bihari servant in Ranchi for a “ghost.” The tale ends with a strong note on the social constructions of the aesthetic facade of a man in contradistinction to a ghost, and how this dichotomy was balanced on an understanding of Victorian notions of outward appearance. Hence, specific categories of low-caste ghosts were marginalized even in their death, as an expression of the powerful afterlife of the stringent specificities of “caste” and “religion” that even death could not transcend. Thus, the socioeconomic and political impact of colonial dominance was translated in the languages of the spectral world through the idioms of religious, social, and gender discrimination, and racial hierarchies.

Ghosts were not always scary or malicious. In some tales, like the Jola ar Sat Bhoot (The Muslim Weaver and Seven Ghosts), they emerged as benevolent figures helping poor peasants out of financial misery, while also representing the spirit of resistance against the oppressive British regime. However, the figure of the benevolent ghost was essentially limited to the sphere of rural narratives, since urban miseries appeared to be apparently incurable even by ghostly benevolence. In the urban narratives, the ghosts appeared more as a threat to the luxuries and comforts, such as electricity, enjoyed by the city dwellers. Socially constructed notions of hygiene associated with poverty, such as bodily stink and dirty fingernails, were regarded as threatening even to ghosts, let alone humans! The poor were outcast even in the domain of enjoying the privilege of ghostly attention in the fiction generated in elite and gentrified urban spaces.

Picking up the thread from where we began, these fictional tales hence remain an unexplored repository for the intellectual historian, portraying how the Bengali mind under colonial transitions revisualized worlds, relationships, normativities, and ideologies. These narratives, both orally transmitted in rural areas and through print in urban circles, generated alternative realities. On one hand, gender restrictions were subverted, on the other, racial hierarchies and rural-urban divisions were reiterated. Reflecting the transitions in a Bengali society caught in the middle of colonial ideologues and nationalist exceptionalisms, ghosts provided Bengalis the voice of hope, faith, and sustenance they needed at the turn of the century.

Shuvatri Dasgupta is a final-year master’s student at Presidency University. Her work revolves around locating the global in the local by analyzing the multilayered origins of cultural and political discourses—tracing their genealogies and contextualizing them in transregional frameworks.

Senjuti Jash is a postgraduate student in History at Presidency University, Kolkata. Her dissertation is about the global intellectual history of caste. She is interested in overcoming the barriers of time and space to discern the intricate webs of connectivities across polities, economies, and cultures in this global age.

Featured Image: A Petni catching fish in a river. Image from Embellished Memories website.

February 13, 2017 at 10:41 am

Reblogged this on O LADO ESCURO DA LUA.