By guest contributor Adrian Young

One can hardly imagine a more audacious ambit for a museum exhibit than that of the Staatlische Museen zu Berlin’s new show, Alchemy: the Great Art, now at the Kulturforum. In the curators’ words:

“Alchemy is a creation myth and therefore intimately related to artistic practice – this idea permeates all eras and cultures, shaping Alchemy’s theoretical underpinnings as well as artistic creativity. An exhibition dedicated to the art of Alchemy is consequently predestined for the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, whose diverse collections stretch over time from pre- and early history to the present. Alchemy is a universal theme for a universal museum”

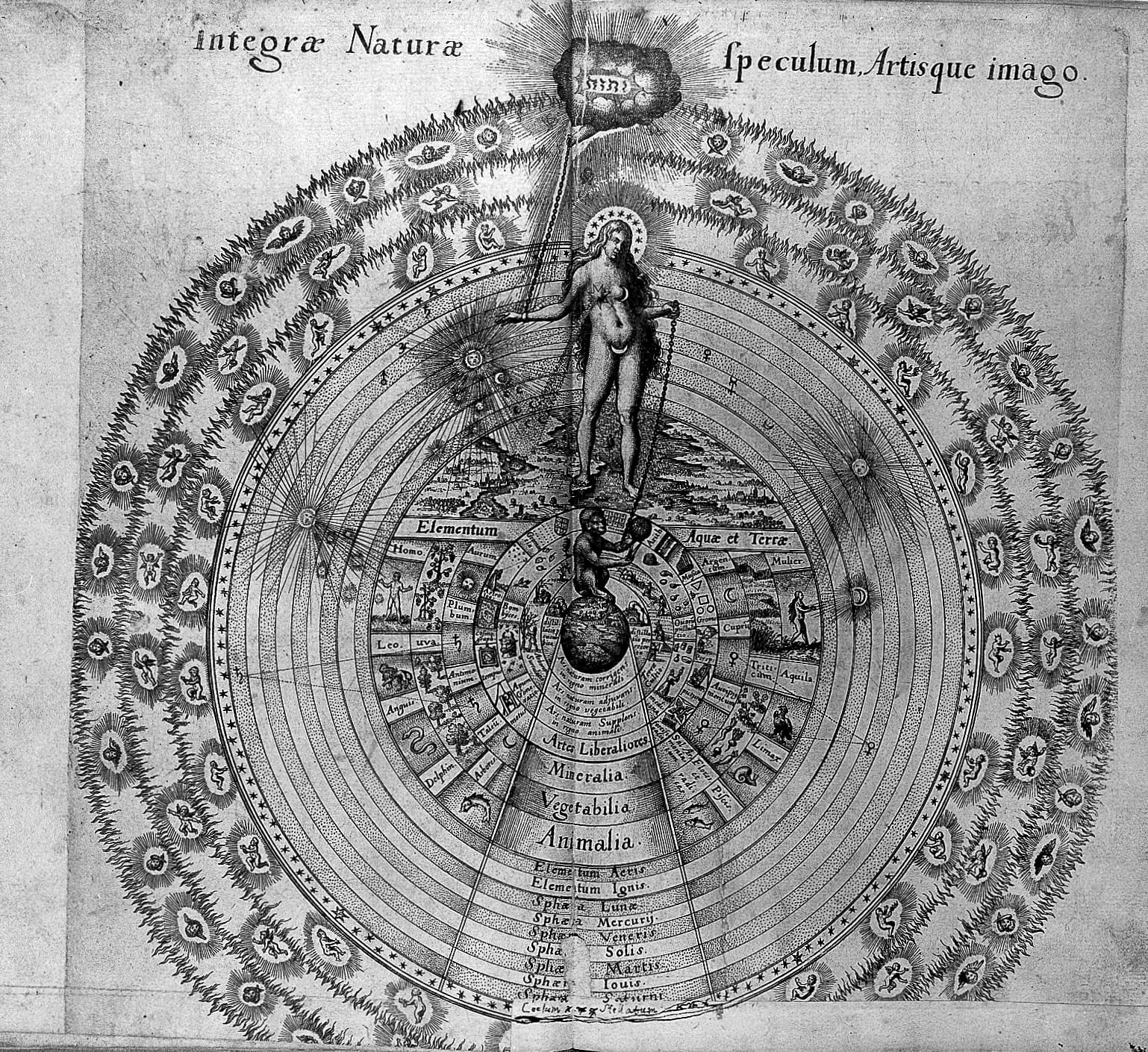

As if to underpin its universal sweep, that thesis is inscribed on a wall above Matthäus Merian the Elder’s beautiful image of the cosmos, published in 1617. Here, the position of the heavens above, the earth below, and humanity in between are assured within a hierarchy ordained by the divine unity of creation. The planets correspond to metals and vice versa, mercury for Mercury, at once products and signifiers of the same heavenly power.

Robert Fludd, Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atque technica historia (1617-1618). (Image courtesy of the Wellcome Library)

From this document, and from the assemblage of some 200 remarkable objects like it, spanning continents and millennia, we are meant to learn something of the universal creative ambition that drove alchemy as a global, timeless, and human craft. As a creative practice, the ars magna (or “great art,” to use alchemy’s medieval European appellation) wedded the pursuit of beauty and the pursuit of knowledge within the same practical tradition. It was only after the advent of Enlightenment rationality obscured their longstanding relationship that art and science seemed to diverge into bifurcating paths. However, though we rational moderns may have lost sight of a creative unity the pre-moderns knew well, by assembling the material culture of a deep alchemical past alongside the artistic products of a scientifically minded present, the exhibit suggests that “art” and “science” need be understood as separate enterprises. Rather, it claims, we have always been modern. We have always sought truth and beauty alike in the manipulation and transformation of material things. Creators have always been alchemists.

It is a seductive and tantalizing notion. Historians might chafe instinctively at claims of universality, as I did when I read the exhibit’s opening scrawl—“this idea permeates all eras and cultures”? But why not? One is inclined to indulge the thought, at least for a moment, while examining the treasures assembled here. And there are treasures. A ding, or ritual cauldron, from thirteenth-century BCE China still draws viewers in with a ring of intricately rendered cicadas; the metamorphosis of these insects suggest that a similar same property of transformation operated inside this metal crucible, and in remains at work in crucibles like it in laboratories and workshops the world over. Wall scrolls by sixteenth-century Daoist artist Lu Zhi depict the search for truth as the work of gathering herbs in the mountains. These hang near sixteenth-century European allegorical representations of the mountainous earth as a temple in which to mine divine knowledge. Alchemical correspondences abound.

Whether these artifacts were products of “art” or “science” is of course a nonsensical question. Indeed, the exhibition reminds its visitors that artists and alchemists were practitioners of allied creative crafts, which they often plied in the same princely courts. A small work by Hans Jakob Sprüngli from the early seventeenth century drives that point home well. In his “Venus and Armor against the backdrop of renaissance architecture,” painted figures are ensconced in a field of gold leaf and stained glass. Master artists, like master alchemists, relied on an intimate, practical, and embodied knowledge of the materials from which they produced their works of truth or beauty. Artists today are much the same in their attention to material things, an alchemical affinity they even share with contemporary scientists. Think of Joseph Beuys, for instance, whose works are represented in the exhibition by a 1986 offprint displaying his “goldkuchen.” In Beuys’s use of fur, fat, and gold, physical objects became agents of affect, begetting emotional reactions and transformations. Pieces by a younger generation of artists do much the same. Sara Shönfeldt’s 2013 series “All You Can Feel (Maps)” is an object lesson in the commonalities of practice between science and art. Shönfeldt placed dissolved chemical compounds like the recreational drug MDMA onto pretreated negatives which, once developed produced full-color portraits of chemicals. Their crystalline browns and greens are reminiscent of minerals or landscapes, feeling simultaneously geological and geographical. It is a use of darkroom technology that recalls earlier work by Walter Ziegler and Heinz Hajek-Halke, also represented in the gallery. Photography and its attendant chemical techniques long provided a practical if little-celebrated bridge between the hands-on work of art and science. Can we meaningfully call those shared practices alchemy? The genealogy, here at least, is manifest.

Continuities with the past need not be happy ones. Deep in the heart of the exhibit, in its lower level, lurks the specter of the homunculus. The artificial being, made living by the alchemist’s manipulation of inanimate matter is also evoked here to suggest alchemical practice’s persistence into our present. Underscoring the idea’s lingering presence in the popular imagination, images of Frankenstein’s monster sit next to a copy of Japanese graphic novel Full Metal Alchemist. That the notion of a monstrous artificial life still haunts us powerfully reinforces the exhibition’s argument; in our era of genetically modified and artificial life, one of alchemy’s chief ambitions is enacted daily in scientific practice. At the center of the “Homonculus” section is one of the “Ripley Scrolls,” on loan from the Getty and one of the exhibition’s most arresting objects. Unwound inside a twenty-foot-long case, it becomes the body of arcane alchemical knowledge now splayed open for visitors. However, the exhibit which most monstrously evokes the grotesque possibilities of alchemical transformation might well be on the floor above, where another of Sara Schönfeldt’s pieces melds scientific and artistic practice. “Hero’s Journey (Lamp)” (2014) stores urine inside a large glass tank, lit by lamps on both sides. The light only penetrates so far through the liquid murk, fading from amber to blood red before disappearing in a dark center of clotted black.

By assembling in one gallery historical objects and art pieces from across time and space, the exhibition attempts a kind of curatorial alchemy, building a synthesis from diverse elements. Like most grand experiments, it falls somewhat short. Though the SMB is indeed a universal museum, Europe’s heritage dominates. While the exhibit proffers alchemy as a universal mode of creation, there are no representative objects from the New World, sub-Saharan Africa, or Oceania with which to substantiate such a claim. East Asian objects appear much more frequently–the Museum für Asiatische Kunst is the source of a number of fascinating exhibits– though these sometimes seem to reaffirm Western narratives. A section on the “chemical wedding” is a case in point. In a famous alchemical allegory, male and female, corresponding to mercury and sulfur, are bonded and give rise to a hermaphroditic compound. It was a notion that originated with Jābir ibn Hayyān and spread in alchemical texts throughout the Mediterranean world, though we see it represented directly only by Western European artifacts. However, we are told that the idea shared an affinity with the wedding of opposites in other traditions—enter a bronze sculpture depicting the marriage of Shiva and Parvati from late eighteenth- or early nineteenth- century Madurai, which gestures at similar alchemical dualities in the Hindu world. The bronze’s precise relation to “alchemy” is sadly unexplained; rather, we are left to ponder the exact global unities between such dualities on our own.

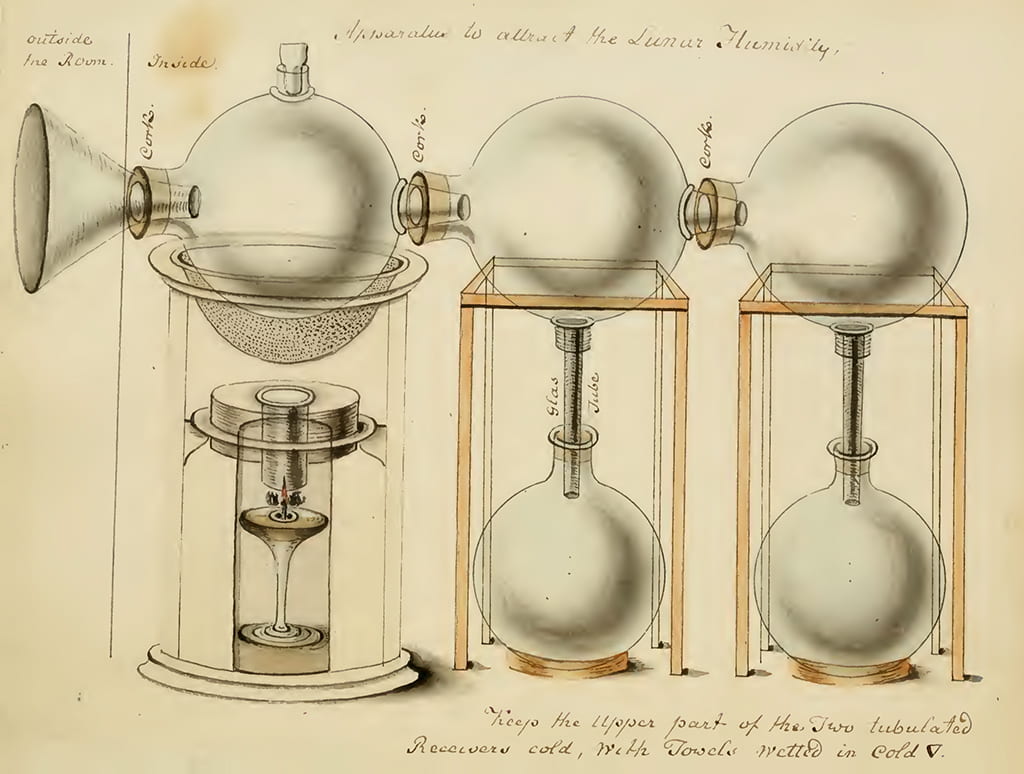

Those artifacts which do receive closer temporal or spatial framings are all the more compelling for it, even if the resulting narratives are in tension with the exhibition’s universal aspirations. Assertions of timeless continuity might productively trouble our understanding of science and art in the present, but historians of science have long offered more circumscribed historically situated assertions of continuity between alchemy, chymistry, and chemistry. In this show, too, the artifacts that best challenge the too-neat dichotomies that seem to separate modernity and reason from premodernity and magic are those that speak evocatively of their own historical moments. Take, for instance, that eminently enlightenment document, the Encyclopedie, whose entry “Chemie” is represented by Louis-Jacques Goussier’s engraving “Laboratoire et Table des Reports,” (1771). Here, a table arranges the traditional signs for the elements, rationally ordering notations inherited from alchemy. Or, better, take the image of Sigismund Bacstrom’s “Apparatus to attract the Lunar Humidity” in Johan Freiderich Fleischer’s 1797 Chemical Moonshine, on loan from the Getty. Here, the glassware of the empirical chemical laboratory (an alchemical inheritance, to be sure) is turned toward the goal of capturing the fleeting essence of moonlight itself. It evokes Yoko Ono, but gestures even more strongly toward the tumultuous, contingent, and fleeting worlds that existed on the edges of the chemical revolution.

Sigismund Bacstrom (German, ca. 1750–1805), “Device for Distilling Lunar Humidity,” ink and watercolor in Johan Friedrich Fleischer, “Chemical Moonshine,” trans. Sigismund Bacstrom, 1797, frontispiece. 950053.4.1 (Image courtesy of the Getty Research Institute.)

Adrian Young is a postdoctoral fellow at the Berlin Center for the History of Knowledge, where he is revising his dissertation “Mutiny’s Bounty: Pitcairn Islanders and the Making of a Natural Laboratory on the Edge of Britain’s Pacific Empire” for publication. Though not a historian of alchemy by any stretch, he maintains an abiding interest in material culture and object lessons.

Leave a Reply