by guest contributor Tess Goodman

The souvenir is a relatively recent concept. The word only began to refer to an “object, rather than a notion” in the late eighteenth century (Kwint, Material Memories 10). Of course, the practice of carrying a small token away from an important location is ancient. In Europe, souvenirs evolved from religious relics. Pilgrims in the late Roman and Byzantine eras removed stones, dirt, water, and other organic materials from pilgrimage sites, believing that “the sanctity of holy people, holy objects and holy places was, in some manner, transferable through physical contact” (Evans, Souvenirs 1). We might call this logic synecdochic: the sacred power of the holy site is thought to remain immanent in pieces of it, chips from a temple or vials of water from a well.

As leisure travel became more common, souvenir commodities evolved from relics. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, tourist-consumers had access to a large market of souvenir merchandise. Thad Logan describes china mugs, novelty needle cases, “sand pictures, seaweed albums,” tartan ware, and a wide range of other souvenir trinkets commonly found in Victorian sitting rooms (The Victorian Parlour, 186). Modern souvenirs are not very different. T-shirts from Hawaii and needle cases from Brighton both rely on the logic of metonymic association, as Logan (186) and Susan Stewart (On Longing, 136) point out. In order to memorialize a tourist’s experiences, the shapes and decorations of these souvenir trinkets evoke the site where those experiences took place.

How did synecdoche become metonymy? What changed? To begin to answer these questions, we can consider a test case: wooden souvenir trinkets from Victorian Scotland. These artifacts draw on both synecdochic and metonymic logic. Therefore, they provide evidence about a transitional phase in the history of the souvenir, and in the history of the way we derive meaning from objects. They do not represent a single moment of transition—this evolution was gradual and piecemeal, taking place over decades if not centuries. Instead, these souvenirs provide a useful case study, a point from which to consider a broader history.

Thomas A. Kempis. Golden Thoughts from the Imitation of Christ. N.p, n.d. Bdg.s.922. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

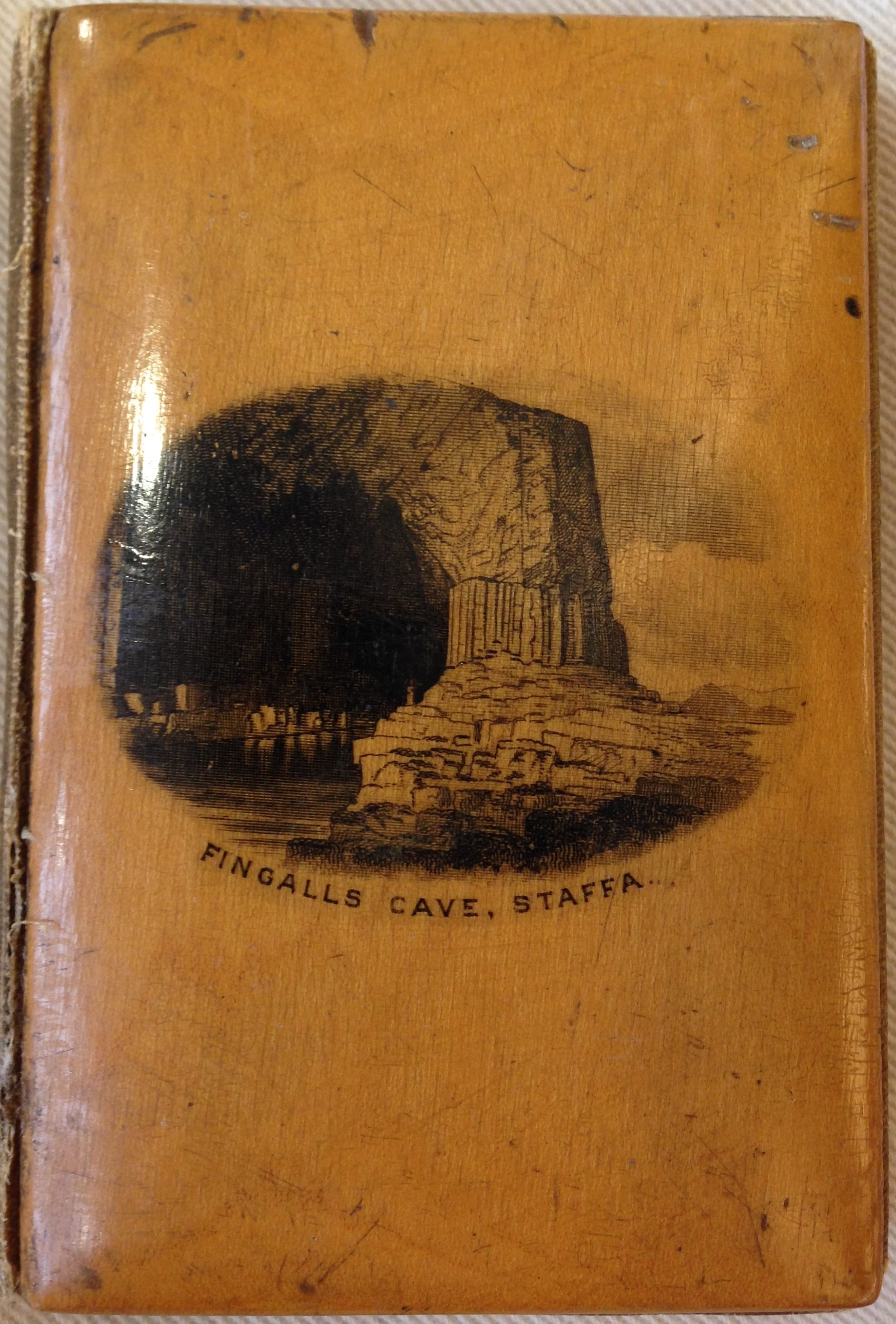

These souvenirs were known as Mauchline ware—named for Mauchline, a town in Ayrshire (Trachtenberg, Mauchline Ware 22-23). Mauchline ware objects were made of wood, decorated in distinctive styles, and heavily varnished for durability. The earliest Mauchline ware pieces were snuffboxes. By mid-century, tourists could buy Mauchline ware pen knives, sewing kits, eyeglass cases, and many other miscellaneous objects. (The examples discussed in this blogpost all happen to be book bindings.) Some of Mauchline ware objects were decorated with a tartan pattern, immediately recognizable as emblems of Scotland. Equally popular were Mauchline ware objects decorated with transfer images of tourist sites. These trinkets functioned with metonymic logic, as modern souvenirs. For example, the binding below bears an iconic representation of Fingall’s Cave.

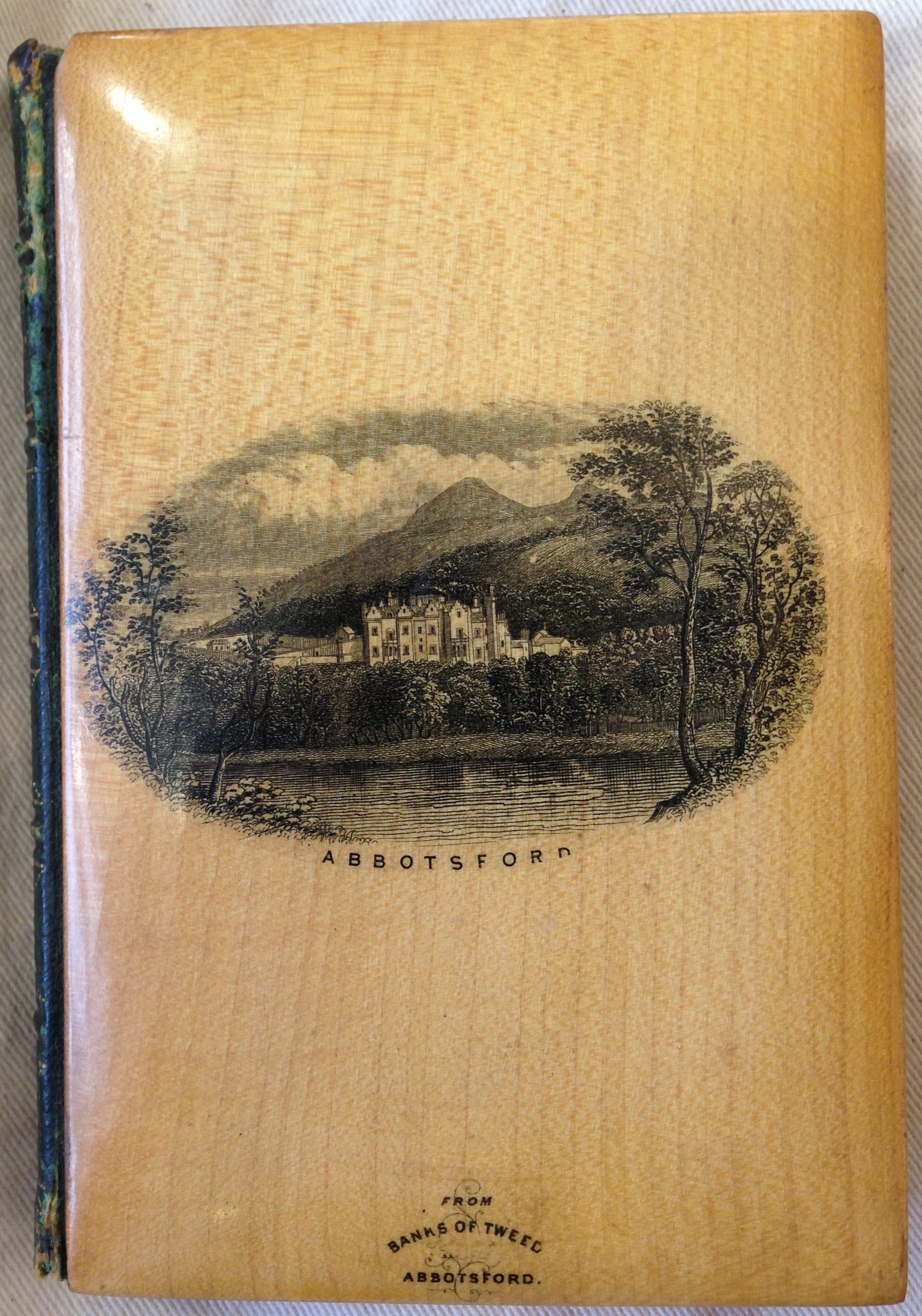

But sometimes, manufacturers of Mauchline ware took lumber from tourist sites to construct these souvenirs. Captions on the items would indicate the source of the material. Examples abound: a copy of The Dunkeld Souvenir was bound in wood “From the Athole Plantations Dunkeld” (Burns). The photograph below shows a copy of Sir Walter Scott’s Marmion bound in Mauchline ware, using wood “From [the] Banks of Tweed, Abbotsford.” More gruesomely, the boards on a copy of a Guide to Doune Castle were “made from the wood of Old Gallows Tree at Doune Castle” (Dunbar). These captions present the souvenirs as synecdochic artifacts—not religious, but geographical relics. Their purchasers could, quite literally, take home a piece of Scotland.

Walter Scott. Marmion. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1873. Bdg.s.939. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

These objects were part relic, part commodity. There was a commercial rationale for this combination: the publishers of these books leveraged the appeal of the wood as a relic, but they also transformed the raw material into a distinctively modern, distinctively Scottish consumer product. Contemporary accounts in a souvenir of Queen Victoria’s visit to the Scottish Borders expose some of the commercial logic behind the production process. Publisher’s advertisements in this 1867 book list the “fancy wood work” items its publishers sold in addition to books, and the original source of the wood used in the souvenirs (The Scottish Border 1-2). The binding on this copy states that the wood was “grown within the precincts of Melrose Abbey.” The advertisement provides more detail:

‘Several years ago, when the town drain was being taken through the ‘Dowcot’ Park, […] a fine beam of black oak was discovered about six feet below the surface of the ground. It is now being taken up […] by Mr. Rutherfurd, stationer, Kelso, for the purpose of being turned into souvenirs. […].’ –Scotsman. Messrs. R may state that most of the “fine beam of black oak” […] split into fibres when exposed to the air and dried. Of the portions remaining good they have had the honour of preparing a box for Her Majesty in which to hold the Photographs of the district specially taken at the time of her visit. (2)

The wood was found on ground between Melrose Abbey and the Tweed, exhumed, and transformed into souvenirs. The publisher’s ad actually refers to these souvenirs as “Melrose Abbey Relics” (2). But they do not adhere to the logic of the early relic: these publishers describe the original wood as quasi-waste material that disintegrated into useless “fibres” when exposed to air. By using the wood for Mauchline ware, the publishers not only preserved the wood against further disintegration: they transformed organic waste into a valuable luxury product, rare and fine enough to present to the Queen. The organic source material lends some authenticity, but it was the process of commodification that added value and intellectual interest.

In short, the relic was not wholly abandoned: the relic and the souvenir co-existed, and some souvenir commodities borrowed ancient synecdochic logic. The gradual, piecemeal evolution from relic to commodity was part of the development of modern consumer culture. The publishers behind these Mauchline ware book bindings were scrambling to reach a new market. Their commercial innovations drew on both ancient and contemporary ideas about the relationships between object, place, and memory. Their publications allow us to consider the changing ideas that allow us to derive meaning from these souvenirs, and from objects like them. Of course, the ultimate meanings of these souvenirs were the personal memories they preserved for their owners. Those meanings remain mysterious, and always will.

Tess Goodman is a doctoral student at the University of Edinburgh. Her research explores book history and literary tourism, focusing on books sold as souvenirs in Victorian Scotland. Previously, she was Assistant Curator of Collections at Rare Book School at the University of Virginia.

September 22, 2017 at 2:25 pm

Found this fascinating article online while seeking information about cultural commodities and souvenir-collecting in the Victorian age. Nicely done–from a former Virginian now also living elsewhere

December 16, 2019 at 4:09 pm

I have a Mauchline ware bookbinding, given as gift to a paternal relative in 1871.

It features a picture of Dunkeld on the front cover & the Falls at Rumbling Bridge on the back with a red leather & gilded spine bearing the title: “Songs”.

The book is entitled the Dunkeld Souvenir by A. McLean & Son, 1869. and contains works by Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, Robert Tannahill & Ettrick Shepherd, etc etc.

If you’re interested in seeing some photos of the book please email me and I’ll be happy to send them to you.

My kind regards,

Howard Mitchell