By contributing writer Brendan Mackie

Clubs were everywhere in 18th-century Britain: there were clubs for church bell ringers, clubs for masturbators, clubs for aristocratic rakes, clubs for collecting art and antiquities, Welsh cultural clubs, clubs for people named Gregory, natural philosophy clubs, literary clubs, radical political clubs, and quotidian dining clubs. London clubs have received a great deal of antiquarian and academic interest. In 2002, historian Peter Clark revitalized club history by showing them to be essential features to an urbanizing Atlantic World. Since them, research on clubs has focused at the role of particular kinds of clubs as cultural institutions. Much attention has been paid to the larger clubs of the 19th century—gentlemen’s clubs, professional clubs—which have more fulsome, better preserved documentation. My research seeks to extend the discussion of clubs by trying to understand why so many men spent so much time and effort to organize their fun in the 18th century. Why did so many people impose rules over their trips to the tavern? What work did this do? To begin to answer these questions, this winter I am trawling through the generous archives of club paperwork in London. There are centuries of attendance lists; centuries of elections, withdrawals and expulsions; centuries of minor administrative resolutions, and centuries of tavern bills.

The problem is that very little of this paperwork illuminates the everyday social experience of clubs. Take the records of the Candlewick Ward Club (established 1739), a dining club for the residents of a neighborhood in the ancient city of London. Three minute books from the club have been preserved in the London Metropolitan archives (CLC/004/MS02841/001-003): big, thick, and promising to this young researcher. Unfortunately, the vast bulk of these records are tedious administrative minutiae: attendance lists, accounts, memoranda, votes resolving to move the club from one tavern to another. They can be quite boring.

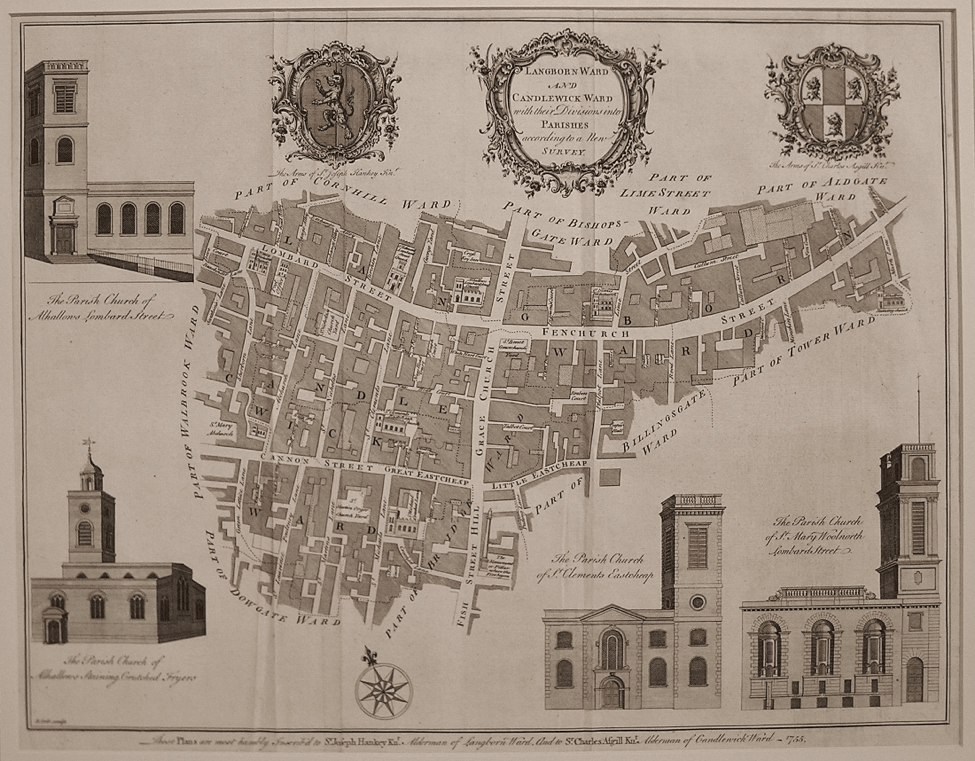

Candlewick Ward (left) and Langborn Ward in 1765 (http://www.storeysltd.co.uk/Item/1276).

Records of wagers frequently interrupt the regular business of the Candlewick Ward Club, however, and these can reveal the slightly muffled echo of the voices in the club room. Bets could only be made for wine (to be drunk by the club), and each bet had to be entered into the club book alongside that day’s minutes. The bets all come from the daily conversation of the club room, so we can read them as fragments of chatter. The members talk much about their city, and how it was changing. The men bet about how long Mr. Munday had been at the King’s Head tavern. Whether there was stained glass in St Leonard’s Shoreditch Church. How long Mr. Abingdon the brewer had been dead for. If the cross atop St. Paul’s Cathedral could be seen from the corner of Gracechurch street. They bet about the big building projects that were radically changing the face of their city, whether the builders repairing the 600 year old London Bridge in 1765 were fully paid (they weren’t), whether the Southwark Bridge would be finished by 1817 (it wasn’t), whether the new replacement for the London Bridge would be opened by 1831 (it was).

They argued about themselves most of all. In 1782, Mr. Stainer and Mr. Hotham bet that they would each be married in the next two months, or else they’d buy the club a rump of beef and a dozen bottles of wine. They remained bachelors and the Club dined on their disappointment. Starting in 1810, early arrivals to the Club Room laid wagers on how many members would turn up that night: a dozen, thirty? Each bet meant more wine for the table no matter who won or lost. In 1813 Mr. Butler bet Mr. Clark about how often he had attended the Club: “He has been 7 times at the Ward club held at the White Hart Tavern, Alchurch Lane within the last two years, the present night included.” The Club Book was brought out, the attendance checked, and Butler was proven right. Joseph Eaton lost a bottle of wine for wrongly insisting that he was five feet five inches tall. That same day Mr. Eaton and Mr. Butler challenged each other to a contest in which they tried to guess the total of all the ages of men in the room—and Eaton lost again. They would bet about who was the tallest, the shortest, the fattest, the oldest, the fifth oldest, or the youngest. They bet about how big their club room was, how long the club’s table was, what material the club’s snuff box was, the circumference of a farthing coin. In 1803 Mr. Walter bet Mr. Bower that Mr. Horne would not make another bet that night. Why?

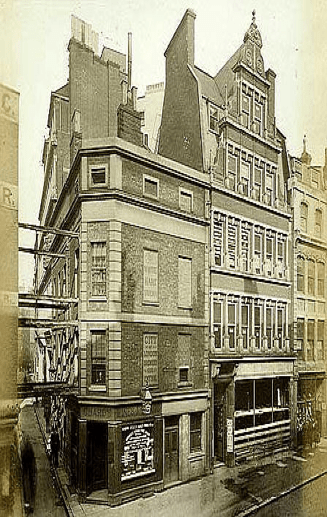

For a time the Candlewick Ward Club met at the White Hart in Abchurch Lane (https://pubshistory.com/LondonPubs/StMaryAbchurch/WhiteHart.shtml)

The club wager is an argument, dulled; a personal disagreement written in the club book in careful hand for all to see; disagreement that can be easily resolved, and once resolved, rectified through wine. Unlike much else in life, the wager was a clear division, with a clear solution. You can imagine them scoffing at one another: “You must weigh ten stone.” “No I don’t.” The club book could be brought out, a wager written in it, bottles of wine laid on either side of the issue, and proof found—a scale, perhaps?—and determination made. It was fun. Fun that the men could challenge one another. Fun that proof could be found to solve these challenges. Fun that this tumble of contradictions, bets and resolutions turned the friction of men into more wine for the table.

Wagers allowed the men of the Candlewick Ward Club some control over uncertainty. They were of minor importance to London life, hesitantly making their way up the ladder of public position. Some were elected to seats on the Common Council. Many served as Alderman and Sheriff. Some had Parliamentary ambitions, rarely, if ever, achieved. One member, Peter Perchard, was actually elected Lord Mayor in 1803, although his election stopped his appearance at club meetings. Within the space of a wager, the impersonal forces clipping the wings of these men’s hopes could be measured, written down, and controlled. They bet on how long a government would survive; who would win the election for the next seat on Parliament or Common Council; whether the Queen would give birth to a child, an heir; whether a crucial law would be passed; whether the men, disgusted with the King, would stand up as they drank his health.

Revealed in other ways, disagreements might offend, but through the wager, the offense could be blunted. In 1763 Mr. Oliver had told Mr. Cole that he would build him a marble chimney; it was obviously taking some time, and Oliver bet a bottle that he would be done that very month. (Whether he did or not remains unrecorded.) Wagers could also be safe vehicles for criticism. In 1804 Mr. Atkinson was confident enough of his chances for being elected to Common Council to bet Mr. Poynter a bottle of wine that he would win; he lost. Six years later Poynter bet that another member, Mr. Gimble, would fail in his bid for the same position. Gimble lost. The club drank his defeat.

The seemingly boring control of club protocol worked to dim the passions so they could be less dangerously expressed. In October 1831, for example, the Candlewick Ward Club memorialized the death of its long-serving secretary Joseph Eaton (who was not five feet five inches tall) in the club’s minute book:

The members of this Ward Club are deeply sensible of the loss they have sustained by the death of their late worthy Secretary Mr. Joseph Eaton whose long service of years in that capacity, as well as in various important duties for the benefit of his fellow inhabitants, accompanied as they were by a strict integrity of conduct and conciliatory manners, justly intitled him to the strongest mark of their respect and which they are desirous of thus recording as a humble tribute of regard to his memory.

This memorial is polite, but it is cold, dry, even somewhat callous. The message of condolence is drafted like any other minute into the Club Book; proposed, then seconded, then voted on by the members present (unanimously); the same form the club would use if it were deciding where to go for its annual country dinner, or whether to admit the new member, or whether to change the meeting place from one tavern to another. But a man was dead. A man who was for a long time a friend and colleague, the father to another member, a man who had been giving compliments of wine to the club on his marriages and on the births of his children for the past three decades. The grief the men felt for Joseph Eaton, that man of “strict integrity of conduct and conciliatory manners” may have been monstrous and inexpressible, as grief so often is; but it would be entered into the club book, in well-turned, polite, respectable, cold, dry, safe language. The grief too could be controlled and contained, like the wager could control and contain disagreement and uncertainty. In this way, the administration of the club rubbed the rough edges off the problems of living with other people, and turned them into the easy good fellowship of yet another bottle of wine placed on a full dinner table.

The Candlewick Ward Club exists to this day, though its members no longer make wagers.

Brendan Mackie is a PhD candidate at UC Berkeley. His podcast is available at historian.live. He is not yet the member of any clubs.

Leave a Reply