By guest contributor Zahra Safaverdi

I see the status of architecture as a “domain of cultural representation” and also knowledge production. Buildings embody the notion of architecture by making physical the manifestation of space via different materials, tectonic characteristics, and orientational attributions; however, they cannot exhaust the architecture fully. The built form is a mere vessel, a proxy for architecture to showcase one dimension of its multifaceted existence.

•

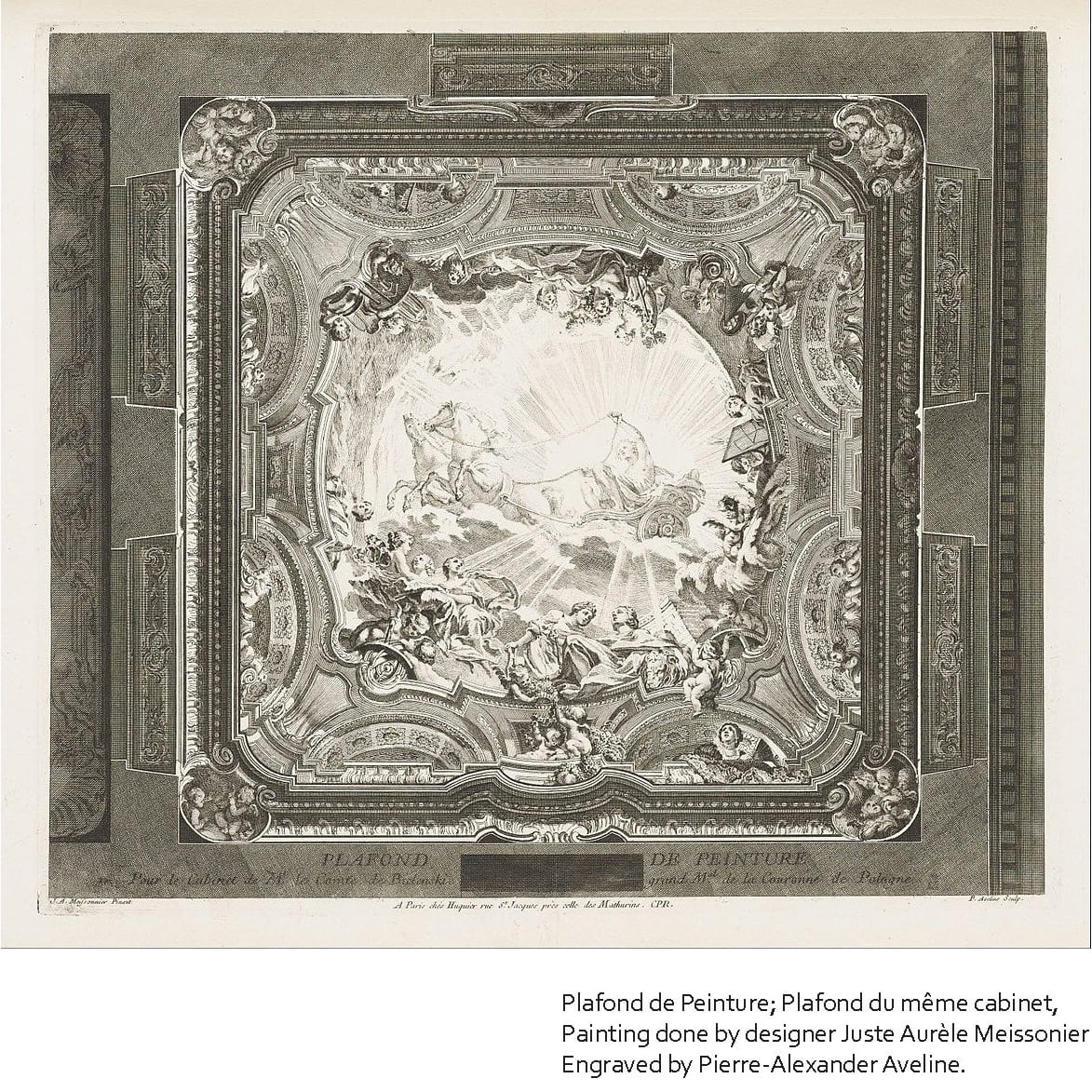

Let’s take a close look at figure number one briefly. Figure 1 represents Plafond de Peinture; Plafond du même cabinet (1740). The painting is done by French goldsmith, sculptor, painter, architect, and furniture designer Juste-Aurèle Meissonier and is engraved by Pierre-Alexander Aveline. The original engraving is currently located in the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. As their record states, the engraving is done for the ceiling of Count Bielinski’s cabinet. “Large central roundel shows a sunburst as background for a mythological scene. A chariot, drawn by two horses and driven by a man is surrounded by female figures, putti, garlands and fruits. Cartouches at the four corners are decorated with putti.”

The engraving depicts a frame which contains another frame inside. The frame inside holds an entire world within itself, depicting a scene from a divine territory. What is striking in this engraving is the role of the intermediate frame: The frame morphs from its traditional definition and assumes a new character: It acquires depth, hence hinting at the frame becoming a three-dimensional space rather than a mere boundary maker. The frame, then, becomes a stage for characters to reside on and not only observe the pictorial world but interact with it, dive into it or emerge from it. Characters could sit on the frame, walk in and out of the frame or morph into the frame itself, shifting shapes and turning into another entity (Figure 2,3,4).

In these engravings, the frame doesn’t divide the world of the image from the real: It connects the two to each other and it blurs the boundaries between them. By providing a gradual tonal transition, the frame becomes an occupy-able threshold allowing free meander between the world of the image and the world of the real.

This seemingly peculiar function of the frame is not specific to Meissonier’s engraving or late Baroque ornamentation. This way of being for the frame is in fact not even peculiar. Ever since modernity, interpreted here as post 1800, the distinction between the product of imagination (the physical manifestation of the image, the world of imagery) and that which belongs to the reality and the normality of the quotidian life has been clear. This clarity, this separation, this profound emphasis on keeping the realm of the real discernible from the realm of the imaginary is the product of modernity.

Looking back at historical references of late Baroque, one could see that this boundary has been rather subtle and there wasn’t a rigid distinction between the two. The framing and ornamentation would turn the pictorial realm of the image into a latent reality, a condition of possibility which needs a small trigger to burst into our world. In late Baroque and Rococo ornamentation, the frame could shift character and attribution and morph into the pictorial realm in a seamless manner. Such characteristics would let different worlds (different depictions) exist adjacent and related to each other without colliding or collapsing. The meandering frame becomes the adhesive holding everything together, weaving in and out of different spaces and preventing the entire construct from unraveling on itself. (For most precise examples take a look at late Baroque churches in southern Germany, as analyzed here. For the purpose of this essay, the following churches have been analyzed in depth: Steinhausen Pilgrimage Church, Weltenburg Abbey Church, St. Johann Nepomuk Church in Munich, Pilgrimage Church of Vierzehnheiligen, Birnau Pilgrimage Church, Zwiefalten Abbey Church.)

With the progression of digital technology, the boundaries between real and imagery are once again blurred in the world at large. As one could observe in many contemporary works in the movie/gaming industry and the art domain, access to virtual reality is not limited to goggles and gadgets anymore and the pictorial realm has already leaked into reality, turning the space of the immersive installation into a liminal zone and a state of in-between-ness. (Take a look at installations done by team lab, the “Void” series of immersive experiments, “Box” by Bot and Dolly, and experiment done in Harvard’s seminar “Mechatronic Optics”.) Given such change, the modernist definition of space- defined based on a didactic grid and forms driven from platonic geometry-needs a revision.

Figure 5

Let us investigate two contemporary installations as examples of environments where the said boundary is blurred. Figure 5 represents the installation “Between you and I”. Here, Anthony McCall defies traditional definitions of space-making by extending the realm of the imagery into the reality. He materializes the virtual world by creating a new interpretation of an atmosphere that is defined by materials that have been traditionally perceived immaterial before. By portraying the light beams as solid, he highlights dust particles and creates an illusive weightless fog. These liminal zones, then, become mediums mediating the two realms and connecting them together in a seamless manner. Sarah Oppenheimer does the reverse action with her spacial installations: By modifying the existing space, she extends the reality into the pictorial realm, hinting at spaces that are present but do not exist in our immediate tangible world. These deceptive liminal zones are distorted reflections of reality, stretching dimensions of the room without occupying extra space (figure 6).

Figure 6

By relying on the historical evidences of late Baroque framing and also evidences in the contemporary art domain, all of which eliminate the need for separation between image and the material world called reality, the possibility of an alternate mode for space and architecture existence would emerge: objects that could act as an occupy-able world with spatial qualities and orientational attributions. These objects provide the moment where the boundary between the imaginary and the real is blurred and the physical rigid threshold is broken. This alternative domain would, then, not only becomes a quasi-physical manifestation of imagery and imagination but a way in which these two realms could be welded to each other with a less pronounced seam: a tight fit that is not just a binary relation between two worlds of the real and the imagery, the normal and not normal. Frames with their latent ability to exist in two paradoxical mode of existence simultaneously, that of separation and that of connection, have the capacity to expand and become a place of in-between-ness and a state of limbo. Introducing occupy-able frames as design elements and re-purposing thresholds, which are seen as program-less spaces now, could be steps toward an alternative mode of space-making. In the architecture discipline, each space inside a building is assigned a specific function and is placed under a specific category called “program” (for example in a house, kitchen, dining room, bedrooms, living rooms are all different program spaces). If the program was the major dictating element of architecture in the modernist approach, here the flow between spaces and the circulation becomes the new driving factor for shaping spaces. Lacan expressed where this is leading us: no one knows anymore whether the door opens to the imaginary or to the real. We are all unhinged.

Why shouldn’t our space be?

Zahra Safaverdi is the Irving Innovation Fellow in Architecture from Harvard University, where she examines new modes of representation of space in the post-digital era. She is one of the current directors of the MASKS event series and the editor of MASKS: journal of dissimulation in art / architecture / design.

Work Referenced, and further reading

Conner, Steven. “Reading Michel Serre.” 20 April 2017, http://stevenconnor.com/ milieux/.

Hayes, Micheal. Architecture’s Desire. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2010. 1-50; 89-134.

Hejduck, John. Mask of Medusa. 1st ed. N.p.: Rizzoli International Publications, 1989. 40-65.

Hendrix, John Shannon. Architecture and Psychoanalysis: Peter Eisenman and Jacques Lacan. New York: Peter Lang, 2006.

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell. Rococo Architecture in Southern Germany. London: Phaidon Press, 1968.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. “Space, Place, and Atmosphere: Peripheral Perception in Existential Experience.” Architectural Atmospheres (2014): 19-45.

Pallasmaa, Juhani, and Peter Zumthor. Sfeer Bouwen = Building Atmosphere. Rotterdam: Nai010 Uitg., 2013.

Picon, Antoine. Ornament: The Politics of Architecture and Subjectivity. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Serres, Michel. The Five Senses: A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies. London: Continuum, 2009. 100-240; 275-300.

Serres, Michel. The Parasite. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Siegert, Bernhard. Cultural techniques: Grids, filters, doors, and other articulations of the real. New York: Fordham University Press, 2015.

Young, Michael. The Estranged Object. N.p.: Graham Foundation, 2015.

Leave a Reply