By editor Derek O’Leary

In the early 19th century, many Americans summoned the history of an antique race from the myriad earthen structures encountered across the expanding frontier. Ranging from small tumuli, to larger animal and human effigies, to colossal conical and pyramidal edifices, these earthworks sprawled from western New York to the Great Lakes, and clustered southward along the Ohioan river banks and up the Mississippi toward the Gulf Coast. The link between a mound-building civilization and contemporary Indians spurred debate until century’s end, but in the antebellum period, most assumed that these advanced predecessors did not—indeed, could not— share lineage with the latter, apparently degenerated tribes.

Summoning the antique mound-builder in this western theater may then seem like the narrative counterpart to vanishing the Indian in the East. (Jean O’Brien’s Firsting and Lasting provides the clearest account of how the latter process played out in the historical societies and commemorative practices of New England; or, if we look to popular culture, Edwin Forrest’s famous portrayal of Metamora; or, Last of the Wampanoags is a striking example of the devastating trope of the “vanishing Indian”.) If the profusion of history writing and popular cultural depictions in this period had indelibly portrayed the American Indian as a fleeting preface to Euro-American civilization, the construction of a distinct mound-builder civilization made him a caesura—mired in historical space, with claim neither to the continent’s antique past nor its progressive future.

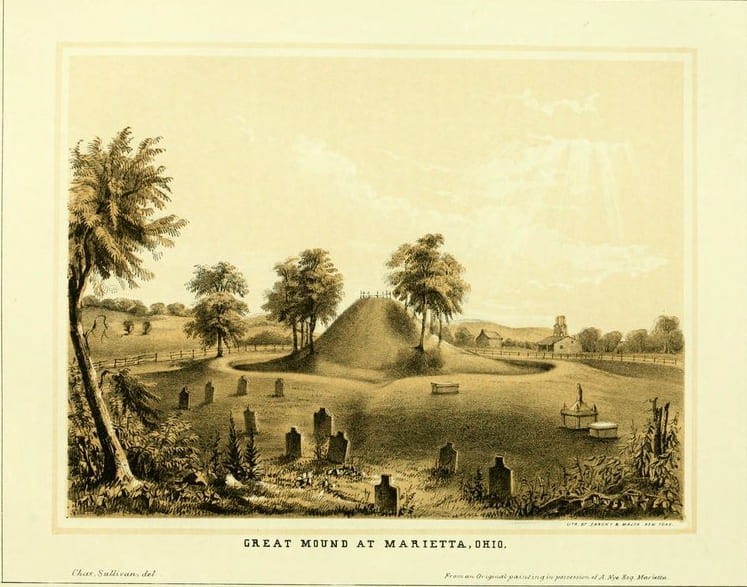

E.G. Squier and E.H. Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (1847)

Late 18th and early 19th-century arguments that contemporary Indians had simply declined from their mound-building époque faded. Counting tree rings on wooded earthworks, commentators increasingly placed mound-builders in the pre-Columbian unknown. Frequently, Indian testimony embedded in these texts concurred. White observers imagined the mounds as the handiwork of a lost tribe of Israel; far-ranging Phoenician mariners; Welshmen or Danes, Egyptians, Moors, or Atlanteans. ( Caroline Winterer’s recent American Enlightenments importantly places this in a hemispheric context, exploring the influence of the Mexican Jesuit Francesco Saverio Clavigero’s Storia antica del Messico (1780) on North Americans’ belief that mound-builders were related to the advanced Toltecan civilization–very useful evidence in rebutting European theories of American degeneracy.) In his massive study of American crania, seminal craniologist Samuel George Morton recognized the biological continuity between the mounds’ architects and contemporary Indians; but he still asserted a cultural rupture that distinguished them as a fundamentally different people, a distinction later espoused in the major archaeological work Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (1848) by George Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis, who had dispatched unearthed skulls to Morton during their earlier mound excavations. (On Squier, see Terry A. Barnhart’s biography, and on Morton’s networks of skull collecting, see Ann Fabian’s engaging account.) As late as 1894, for instance, retired British naval captain Lindsey Brine, following his wide-ranging tour of North American mounds, could conclude that some medieval Atlantic crossing of “European, Moorish, or Asiatic races” had ferried the mound-builders westward. Some outstanding skeptics had persisted in challenging these notions, such as American Antiquarian Society librarian and archaeologist Samuel Haven, in his 1855 Archaeology of the United States (the second major publication by the Smithsonian Institution). However, only in its encyclopedic 1890 survey of American Indian societies, based on decade of research into the matter, did the American Bureau of Ethnology resoundingly debunk lingering belief that American Indians were distinct from the mound-builders.

In the meantime, however, hundreds of speculative works—from slight to expansive—on the western mounds circulated. From one vantage point, they may sound like many chorus members in the cant of conquest. Some recent scholarship on the mounds takes this stance, focusing on the discursive violence done by the mythology of the mounds; undoubtedly, racism was near the core of European-American disbelief that the 19th-century Indians could have descended from peoples capable of piling large amounts of dirt and sustaining sedentary societies. From another perspective, though, histories of archaeology—often presentist accounts of how that discipline attained its modern form—gape at the odd array of origin stories that Americans and European visitors perceived in the mounds.

However, between these two broad takes on the reams of popular and scientific writing about the Indian mounds—either as scripting the American Indian out of the national story or as the risible rudiments of modern archaeology—we can excavate the many uses Americans made of the mounds. Americans increasingly surged westward over the Alleghenies after the War of 1812—such watery metaphors for this migration are common: deluge, flood, wave. On the ground, though, it amounted to innumerable individual encounters with these earthworks. Most settlers, we can imagine, simply built their lives around or upon or from these overgrown vestiges, recording no reflection about them. Other settlers, travelers, and researchers, however, gazed upon them in starkly divergent ways (not unlike individuals’ varied approaches to the documentary records of the American past scattered along the East Coast). These encounters swung among disregard for, exploitation of, and obsession with the preservation of the mounds: they became ready source of soil and fill for new farms and settlements; their interiors yielded artifacts to be trafficked for personal and institutional prestige or financial profit; and their alleged evidence for an antique American civilization could act as a specter of decline, model for national growth, or grist for other cultural productions. But, whether mundane or stirring to the westward traveler, such mounds were pervasive, undeniable features of what white Americans encountered in the western landscape. Prolific excavators claimed to have surveyed hundreds, and the most enthused commentators calculated or imagined many thousands, once peopled in the millions.

As the number of surveys mounted, the genre narrowed. Dry measurement and accounting of mounds piled up, suggesting that the performance of the ritual and publication of the record held as much value as the objects or stories exhumed there. These uncovered earthworks stimulated a much broader interest in surveying, the inchoate fields of anthropology and archaeology, and the general uncovering of the continent’s record, often deposited in emerging historical societies and archives. Romantic notions of a landscape imbued with an antique past inspired professional researchers and charlatans alike, but their scientific findings also grounded the contemporary literary excavations of the mounds. Readers consumed fictionalized accounts, which transported them westward and into the depths of time. Sarah Josepha Hale, later famous for her decades-long stewardship of Godey’s Lady Book and campaign to institutionalize Thanksgiving, emerged into the literary world in 1823 with a phantasmagorical poem of Phoenician settlement of North America, “The Genius of Oblivion”. Lying upon a mound, her hero, Ormund, falls into a reverie of this ennobling but impenetrable past:

To know from whence, and who these were ?

How came—how perished they ? And where

The archives of their history,

Their tomes of kings, forgotten lie ?

But vain these wishes throng his mind,

Vain as yon Circle’s end to find !

Notably, though, substantial footnotes follow the lyric text, showing that from her desk in Boston she was immersed in western archaeological findings. In his 1839 novel Behemoth: A Legend of the Mound-Builders, Cornelius Mathews, of the Young America literary movement, announced, “The hour has been when our own West was thronged with empires.” Briskly, he stages an epic confrontation between a mound-building civilization led by something of an indigenous George Washington and an apocalyptic mammoth, satisfying at once desires for a robust national and natural pre-history. Exalting the memory of this imagined civilization, he also laments its leaders’ material remains, ravaged by the sexualized forces of nature, “Yon mound, consecrated by the entombed dust of a generation of sages and heroes is embowelled, and its holy ashes laid open to the vulgar air and the strumpet wind.” Perhaps countervailing these forces, after his vivid animation of an antique mound-builder drama, he densely packs a full third of his 200-page book with reference notes on archaeology.

Glimpsed in these material, scientific, and literary uses, the mounds fulfilled varied and interwoven needs of nation-building in the early United States: farmers carted of soil and treasure hunters sifted through it; would-be archaeologists sketched mounds and authors scripted ancient dramas upon them.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uoqVfDEm5Rk&w=854&h=480]

(The full 348 feet of John Egan’s 1850 “Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley.” The full panorama, including numerous depictions of mounds, is maintained at the St. Louis Art Museum.)

To bring us closer to the many real encounters with the material past of the continent, directed to these varied ends of the present, we can imagine one scene. On a July day in 1852, in Auburn, New York, a congregation assembled to dedicate the new Fort Point Cemetery, built atop a prominent Indian mound—an “eminence”, some one hundred feet overlooking the town. Admitting that they could know but little of its first inhabitants, the introductory remarks nonetheless proposed that,

…we may well believe that their mouldering dust is mixed with the soil beneath us; nor would it be a wild stretch of the imagination to fancy that their immortal spirits may be permitted to hover near us, and to witness the solemn ceremonies of this day.

The sermon was published in a historical guidebook for visitors. As it notes after extensive historical background on the mound-builders, the land was previously occupied and abandoned by Cayugas (of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy), and thought the birthplace of the famed Indian Logan. This deep and varied history is compressed and choreographed in the site of the new cemetery—transmuted to a chronotope, to borrow Bakhtin’s term. Seizing these material grounds, archiving their physical traces therein, summoning the dead’s spiritual force, almost retroactively proselytizing them, and then selling the narrative to tourists—in that brief moment on a mound we can perceive a truly useable past.

Leave a Reply