by Editor Sarah Claire Dunstan.

One summer’s afternoon in 1923, a French barrister was enjoying a drink in a Parisian café. A man of broad experience and education, the barrister was also a medical doctor who had served in the First World War. This service had allowed him to become a French citizen in 1915, a privilege denied previously because he was a native of the former Kingdom of Dahomey, now a French colonial territory. Kojo Tovalou Houénou

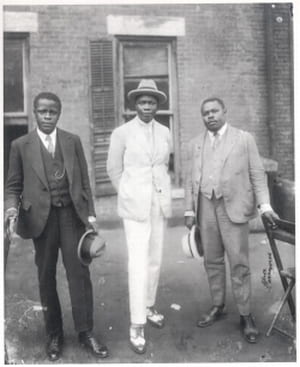

Comtesse de Ségur of the Comédie Francaise

was not just from Dahomey, he also claimed the title of Prince on the basis that his mother was the sister of the last King. Contemporaries and later scholars doubted the veracity of this claim but it made him of much interest to the Parisian dailies. In their pages, tales of his exploits amongst bohemian circles – notably his on-again, off-again affair with the Comtesse de Ségur of the Comédie Française – were reported with glee.

On this particular August afternoon, Houénou was simply a French man. Or at least he was until a group of drunk Americans sat down at a table nearby. He thought little of them until they began to object, loudly, to his presence. The waiters, virtuous Frenchmen one and all, refused to eject Houénou from the café but the Americans grew rowdier. Finally, the foreigners stood up, dragged him from the café, beating him up and throwing him in the gutter. This example of American racism shocked Houénou, awakening him to the reality of black experiences outside of la belle France. He resolved to do all that he could to extend and uphold the principles of French civilization and to protect the less fortunate amongst his race. To this end, Houénou founded the Ligue Universelle pour la défense de la race noire and its journal, Les Continents. This very tale was printed in one of the early issues and reiterated as the origins story for the Ligue by other press outlets such as the African American journal the Crisis and Marcus Garvey’s newspaper, the Negro World, as well as by Houénou himself in speeches delivered to mainly black audiences in Paris and New York.

Although primarily concerned with abuses being perpetrated towards the indigenous populations in the French colonies, Les Continents became one of the first francophone print forums for collaborations between African American activists and thinkers and their French counterparts, crafting a bridge between Harlem and the Parisian left bank. The Ligue itself had a mission statement that articulated its desire to ‘develop the bonds of solidarity and universal brotherhood between all members of the black race.’ Celebrated Harlem Renaissance figures from Alain Locke and Langston Hughes through to Countee Cullen published in the journal. Under Houénou’s leadership, the group built relationships with the American National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. As a result, the Ligue has received some scholarly attention as an institution that fostered black international solidarity (most notably in Brent Hayes Edward’s wonderful The Practice of Diaspora, Christopher L. Miller’s Nationalists and Nomads and Michael Goebel’s Anti-Imperial Metropolis.) More than that, Houénou’s neat origin story has much in common with those employed contemporaneously by other black activists as they attempted to leverage the potential of French civilization against the specter of American racial discord and to agitate against racism in France. Insofar as the existing scholarship is concerned, Houénou tends to appear in histories of black internationalism that focus upon institutional organization or ideological mechanisms. Where his activism is given credence, it is as a corrective to the scholarship’s tendency to focus upon the African American presence in movements towards black internationalism. Always, Houénou’s experience is subsumed in the institutions he founded or participated in.

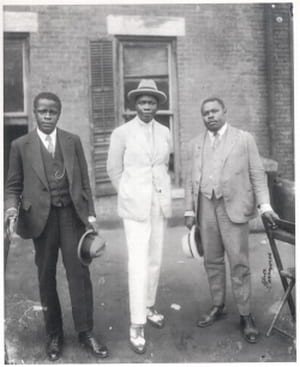

From left to right: Marc Quenum, Kojo Tovalou Houénou and Marcus Garvey in Harlem, 1924.

This is due in part to the scarcity and nature of remaining sources. No archive holds Houénou’s personal papers. Fragments of his life have to be pieced together from newspaper articles from his heyday in the Parisian social landscape, or from letters appearing in other collections such as that of W.E.B. Du Bois. The Service de contrôle et d’assistance des indigènes, established by the French Minister for the Colonies Albert Sarrault in 1923, offers perhaps the most comprehensive chronology of Houénou’s life. Given that Sarrault utilized the Service for surveillance of those deemed threatening to the French imperial system, this tends to emphasize his involvement in black activist organizations rather than pay heed to his individual behavior. All the more so given the French authorities’ tendency to conflate all Pan-Africanist organization with Garveyism and all Garveyism with insurrectionist and usually Bolshevik politics. When Senegalese politician Blaise Diagne successfully sued Les Continents for libel in 1924, the paper and the organization folded, leaving Houénou bankrupt. He was forced to leave Paris and to renounce his diasporan affiliations (specifically any connection with Marcus Garvey) before he was allowed back into Dahomey. Black international solidarity at this moment, then, appeared to crumble in the face of the machinery of French Third Republic.

Inverting the study to map an international history through Houénou’s individual perspective, however, changes the narrative from one of failure at the hands of unstoppable empire. Instead it allows us to re-position the way we think about the spatial geography of black internationalism which is often characterized in terms of experiences in Northern hemisphere metropoles. Houénou himself participated in the construction of this narrative with his repeated telling and refashioning of the café incident. The Ligue and the other black activist organizations he participated in certainly were rooted in Paris and New York. Moreover, the freedom of speech permitted in Paris as opposed to the colonies created a space for black internationalism that would not have been possible elsewhere. However his own individual experiences belie the story he constructed.

In 1921, two years prior to his ‘racial awakening’, he had visited Dakar. Whilst there, he spoke to the Senegalese tirailleurs who had been abandoned by the French Government after fulfilling their conscripted duties. The reality of their exploitation was only too visible and Houénou spoke out to local authorities about it. He was ignored. Soon afterwards he published a little-read book entitled L’Involution des métamorphoses et des métempsychoses de l’univers. In it, he attacked European assumptions of cultural superiority by arguing that each people and culture comprised equal parts of a universal civilization. Early in 1923, in the aftermath of rioting in Porto-Novo in Dahomey, he criticized the colonial administrators’ handling of the issues, to little avail. True, neither incident was quite so personal and dramatic as being beaten up in a Parisian café but they do indicate a public engagement with the question of race on an imperial, if not an international, level much earlier than narratives focusing upon the Ligue or his UNIA support allow. It also locates the site of his racial awakening outside the colonial metropole.

This reframes our understanding of the valency of a racial awakening in Paris rather than Porto-Novo or Dakar, pointing to the way that gestures of black solidarity were sometimes easier to perform in the metropole than elsewhere. In particular, it demonstrates the crucial symbolic role that examples of US racism played in francophone black activism at this time. This is especially clear when one looks beyond Houénou’s sanctioned version of the story to the one relayed in other sources such as the Parisian press: it was a French bartender who threw Houénou from the premises and beat him, not the crowd of racist Americans who bayed for his removal. Moreover, Houénou’s activities after the collapse of the Ligue and his departure from Paris lead the historian away from the print formulations of universal black brotherhood found in Les Continents to their application on the ground in Africa.

Hardly a year after his relocation to Dahomey, Houénou and a group of unnamed allies attempted to overthrow French colonial rule there. His movement was small, ill-equipped and failed spectacularly. Forced to flee to Togo, Houénou was quickly caught and imprisoned. Some reports indicate that he was incarcerated for five years, others three. What we do know is that he was never allowed to enter Dahomey again. Instead, he went to Senegal by 1930, possibly as early as 1928, and became heavily involved in Senegalese politics. At first he supported Ngalandou Diouf against Blaise Diagne in the elections of 1932. He would switch candidates for the following election of 1934, supporting Lamine Gueye against Diouf. In both cases, Houénou applied a committed Pan-Africanism of the type that the French colonial authorities feared Garveyism represented: the call for the recognition of the equality of all races and the independence of African territories from colonial rule. Neither Diouf nor Gueye were quite so radical in their views. Indeed, Houénou’s platform was far removed from the Parisian story that played American racism off against la belle France. His early cries for universal black brotherhood had transformed at the hands of the treatment of colonial authorities to his support for the total independence for Africa.

Houénou’s involvement in Senegalese politics is usually not considered in the context of black internationalism. To be strictly honest, it has not exactly earned him a noteworthy place in the annals of Senegalese history either. He met an ignominious end in the electoral campaign of 1936 when the meeting he was running exploded into violence. Nevertheless, by focusing on Houénou’s own story, rather than solely upon his involvement in the international and diasporic institutions he helped to build, it is possible to shift the geography of black internationalism away from imperial metropoles back to the African continent.

Sarah Claire Dunstan is an ARC Postdoctoral Fellow with the International History Laureate at the University of Sydney (@IntHist ). She is an intellectual historian of 20th century France and the United States with a particular interest in questions of race, rights and gender. She can be found on Twitter @sarahcdunstan .

2 Pingbacks