Sundry readings from our editorial team this week:

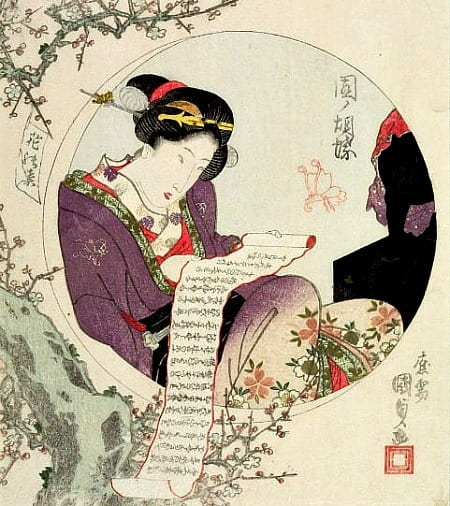

Utagawa Kunisada,

Woman Reading Libretto (1823-5)

AJ:

Alina Cohen, “The Legendary Bars Where Famous Artists Drank, Debated, and Made Art History” (Artsy)

Lungisile Ntsebeza, “This Land is Our Land” (Foreign Policy)

Ronald Brownstein, “American Higher Education Hits a Dangerous Milestone” (The Atlantic)

Shaun Manning, “The White House Correspondents’ Dinner’s Controversial Jokes… in Action Comics Special #1”(Comic Book Resource)

Nuala:

Minsoo Kang, Catapunk: Toward a Medieval Aesthetic of Science Fiction. (Boydell & Brewer)

Hanna Kokko, Give one species the task to come up with a theory that spans them all: what good can come out of that? (Proceedings of the Royal Society B)

James Alexander Wearn, Seeds of Change — Polemobotany in the Study of War and Culture. (Journal of War and Culture Studies)

Vinciane Despret, What Would Animals Say if We Asked Them the Right Questions? (University of Minnesota Press)

Cynthia:

Frieze NY is on. Art fair openings always feel, at least to me, a bit like the first day of school. The air is bubbly. Are you in or are you out? These days, a spate of articles denouncing the art fair heralds the arrival of each art fair. They rehearse a litany of (legitimate) criticisms: The fairs are too big. They are too expensive (according to Jerry Saltz, “A large booth costs $125,000. A gallery can sometimes pay another $15,000 to $18,000 to build out the booth. On-site handling costs can run another $5,000). Only the blue-chip galleries make any money. Of course, most of the critiques revolve around art-as-business. It’s all fun and games until the realization hits: art is made by artists. And artists are flesh-and-blood human beings, not manifestations of cultural capital or the cultural economy or the superstructure, or whatever theoretical construct we find most apt for our argument.

Are you in or are you out? Being on the inside, having access to all that capital and all those connections, can mean the difference between surviving (i.e., paying the bills, eating, having a place to sleep), or not. The mainstream press loves to focus on the artists who command stratospheric prices, but most artists are not superstars and do not travel with retinues of celebrities. A recent NYT article asked if artists with day jobs make better art, as if day jobs somehow complement and elevate the practice of art. Well, let me assure you that most artists do not take day jobs because they believe in complementary practices. Most artists have day jobs because they need them. Day job or not, artists need to get past the gatekeepers in order to get on the inside. And if there’s one thing history has taught me, it’s this–”Don’t trust the gatekeepers.”

Aruna D’Souza’s thoughtful review of “Outliers and American Vanguard Art” (at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) argues that one of Lynn Cooke’s goals, as the curator of this exhibition, was to “signal another way through the American visual landscape of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries,” by proposing a historical narrative that acknowledges, and incorporates “makers, ideas, and practices that modernism has long resisted, or only accepted begrudgingly: craft processes, regional idioms, traditional “women’s work” such as textile arts and beading, the work of black and Chicano artists long ignored by mainstream art history, the role of religion and spirituality in American visual culture, the artistic value of utilitarian objects, the unironic, artists making installations in their backyards, and so on.” What would such a history of American art look like?

Derrick Adams takes on the precarious status of the outsider from a very different perspective in his exhibition,“Sanctuary” (Museum of Arts and Design). “Sanctuary” grew out of Adams’s meditations on The Green Book, “a series of AAA-like guides for black travelers published from 1936 through 1966 […] Widely used at a time when African-Americans were navigating physical and social mobility through the swamp of Jim Crow laws and attitudes in the mid-20th century, the Green Books, as they came to be known, listed businesses from gas, food and lodging to nightclubs and haberdasheries that welcomed African-Americans when many did not.” Segregation meant that African-American travelers were excluded from a wide range of establishments, and had to be mindful of “sundown towns,” where African-American travelers were not welcome after dark. The Green Books, Adams noted, “enabled African-Americans to travel like Americans and to feel American,” despite the legal and institutional structures that kept African Americans on the outside, unable to fully inhabit the American Dream.

Sarah:

Stefan Collini, “Diary: Why Have They Done This?” (LRB)

William Davies, “The Windrush Scandal,” (LRB)

Anna Russell, “Sketching the M.T.A. with a Subway Archaeologist,” (New Yorker)

Jacob Hamburger, “Tocqueville, soixante-huitard?” (Tocqueville21)

Peter Hessler, “Cairo: A Type of Love Story,” (New Yorker)

Derek:

Robert Greene II, “Misremembering 1968” (Religion and Politics)

Errol Morris, “Is there such a thing as truth?” (Boston Review)

David Wallace, “Fred Wallace’s Radical Critique of the Present” (New Yorker)

Marcus Rediker, “The forgotten prophet” (aeon)

Leave a Reply