By Fiore Sireci. See the full companion article, “‘Writers Who Have Rendered Women Objects of Pity’: Mary Wollstonecraft’s Literary Criticism in the Analytical Review and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” in this season’s Journal of the History of Ideas.

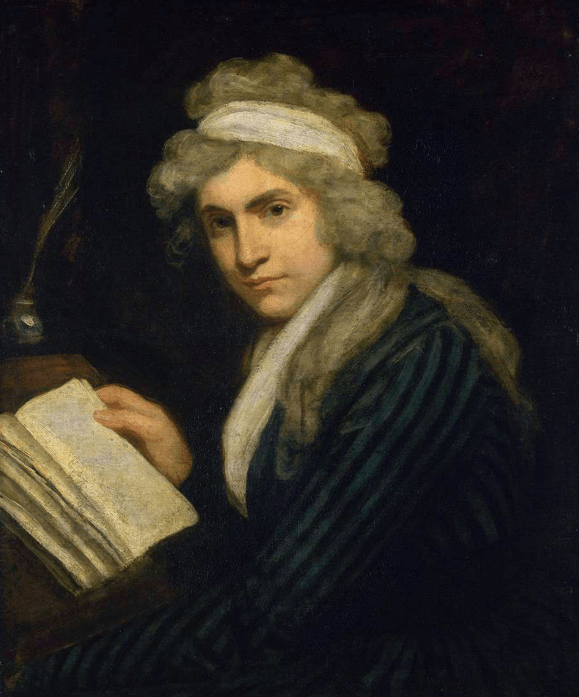

How did Mary Wollstonecraft, the “mother of modern feminism,” spend her days in the year leading up to the publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)? Her reading audience had little clue about the private Wollstonecraft until she died just 5 ½ years later. At that point, her widower William Godwin pulled back the curtain on a life that Wollstonecraft had carefully kept from view while she built up an impressive public image. They were transfixed (and mostly scandalized) by the complexity, drama, and heartbreak of her story, but much of that drama and heartbreak happened after the publication of Rights of Woman. Nevertheless, Godwin’s Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798) set up a pattern that continued for nearly two centuries: a focus on her emotional journey rather than on her work life.[1] I’d like to ask the question anew and look at the Wollstonecraft of 1791, the Wollstonecraft who had a professional life as a well-established literary commentator, and see if this opens new perspectives on her most famous work.[2]

During her lifetime–before she was known as the reckless Wollstonecraft who had a child out of wedlock (1794), or the desperate Wollstonecraft who twice attempted suicide (1795), and even the political Wollstonecraft who wrote two Vindications–she was already well-respected as an anthologist, educator, translator, and as a very active reviewer of books, for which she was paid well. Due to the irreplaceable spade work of Ralph Wardle, and scholars such as Janet Todd, we now have a good idea of which of the many anonymous and semi-anonymous reviews in the liberal Analytical Review can be attributed to Wollstonecraft. By the time she wrote Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft had penned well over 200 of these, and by her death at age 38, over 350.

Wollstonecraft’s reviews are not merely a distant accompaniment to her ideas in Rights of Woman, or as some have suggested, a rehearsal of the “tart” language in her most famous book. Her professional practice helped shape Rights of Woman in both style and substance. Her primary argument, and innovation, is that gender is shaped by culture, but that argument is primarily activated by critiques of well-known texts, and those critiques are in turn the fruit of a long period of intellectual gestation as a literary commentator and theorist.[3] One of the most prevalent approaches was one that has frequently been used on Wollstonecraft herself, that is, to see the text as symptom, but she and her contemporaries did not do this blindly. They also undertook comparative analyses of passages within and between texts, looking for threads of sympathy, intellectual and otherwise. Wollstonecraft built on this practice and in Rights of Woman she presented evidence, in the form of “illustrations,” to demonstrate that text was a powerful factor in the social construction of gender.

Eighteenth-century literary critics also mastered the rhetorical art of casting themselves as characters with powerful feelings, and it was through these carefully crafted public selves that they hoped to sweep their readers along to agree with their points of view on anything from politics to how raise children. This was the heyday of emotionally embodied literary criticism. In non-fiction there was Addison’s easy coffee-club manner in the Spectator (early 1711-1714), Samuel Johnson’s cantankerous wisdom in his Rambler essays (1750-1752), and Clara Reeves’ wise literary woman in The Progress of Romance (1785). In fiction, we can consider Charlotte Lenox’ Female Quixote (1752) as well as the youthful Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (completed 1803). The reader-as-character was ubiquitous because reading itself was an issue of great concern and anxiety in an age when, as Jürgen Habermas has shown, the “literary public sphere” was where political change originated. Mary Wollstonecraft fully participated in this literary culture, presenting critical and profoundly thoughtful selves in both fictional and non-fictional genres (sorry for the somewhat anachronistic categories). In other words, the virtual Wollstonecraft was constructed over a number of years and in many different genres. She is: the brassy and empathic governess in Original Stories (1788, illustrated by William Blake), the judicious editor of readings for young women in The Female Reader (1789, contested attribution), and the righteous female republican in A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), but her most frequent appearance was as the sharp-witted, discerning, and often merciless book reviewer in Joseph Johnson’s monthly publication, the Analytical Review.

The demonstrative reader-writers of Wollstonecraft’s time sometimes resisted texts and other cultural forces, and sometimes dramatically gave in. In Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), the anti-revolutionary and increasingly conservative MP Edmund Burke recalls being moved to tears at seeing the young, graceful, royal figure of Marie Antoinette, so light, so ethereal her feet barely touched this corrupt “orb” of our earth. In her response, Wollstonecraft immediately recognized this fawning sentimental gesture as a familiar and potent literary move. But knowing that Burke was also an active reviewer (and founder of the Annual Register), as well as the youthful author of a treatise on the very topic of susceptibility to aesthetic stimuli, On the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), Wollstonecraft’s analysis of Burke traces the deep philosophical roots of his position, and in doing so her political argument is activated through cultural and literary criticism.[4]

Wollstonecraft’s extensive focus on books in her second Vindication was an extension of her approach in her first Vindication. Again, chronology illuminates. Rights of Men was completed in late 1790 and the second edition was published in early 1791. In the last section, Wollstonecraft promises a continuation and expansion of her literary approach:

And now I find it almost impossible candidly to refute your sophisms, without quoting your own words, and putting the numerous contradictions I observed in opposition to each other.

Rights of Woman was begun within weeks of this statement, if not earlier, and the first in depth critique in the book, which Susan Wolfson has dubbed “the genesis of feminist literary criticism,” features extensive quoting of John Milton and juxtaposition of passages from Paradise Lost. She does the same with Rousseau and many other writers throughout the book. Could it be, though, that Wollstonecraft had been pondering her great Vindication even before 1791, her thoughts on books nursed over the course of her experiences as a governess in Ireland, a founder of a girls’ school in the Dissenters’ community of Newington Green, and her job reading reams and reams of print since 1789?

In any event, between February and November of 1791, when it seems Rights of Woman was completed, Wollstonecraft had written another four or five dozen reviews. Some of these reviews picked up and extended the concerns of her growing literary critical practice, especially when she takes a good hard look at Rousseau’s Confessions, where she’s harder on her fellow critics than on Rousseau himself: “[T]hough we must allow that he had many faults which called for the forbearance of his friends, still what have his defects of temper to do with his writings?” This was written in December of 1791 when Rights of Woman was being typeset, a crucial fact when we juxtapose this statement with Wollstonecraft’s dismantling of Rousseau and other influential male writers in her treatise, sometimes accompanied by breathtaking ad hominem.

Speculations on the emotional state of an author are found throughout Rights of Woman. However, Wollstonecraft also takes a step back and questions the interpretive theory itself, as in this statement from Chapter 5: “But peace to his manes! I war not with his ashes, but his opinions,” and this is followed by another extraordinary implication: “I war only with the sensibility that led him to degrade woman by making her the slave of love.” In other words, she characterizes Jean-Jacques as himself subject to cultural and psychological pressures. The great man as vulnerable weather vane of culture appears again here: “Rousseau’s observations, it is proper to remark, were made in a country where the art of pleasing was refined only to extract grossness of vice,” in Chapter 5. Milton is also subject to a psychological reading. In Chapter 2, Wollstonecraft’s juxtaposition of allegedly contradictory passages from Paradise Lost is meant to reveal the emotional instability that can beset even the most respected writers. Wollstonecraft explains that, “into similar inconsistencies are great men often led by their senses.” Wollstonecraft places the most influential writers in the role that young women had been placed in for over a century, as hapless and indiscriminate readers sponging up cultural influences.

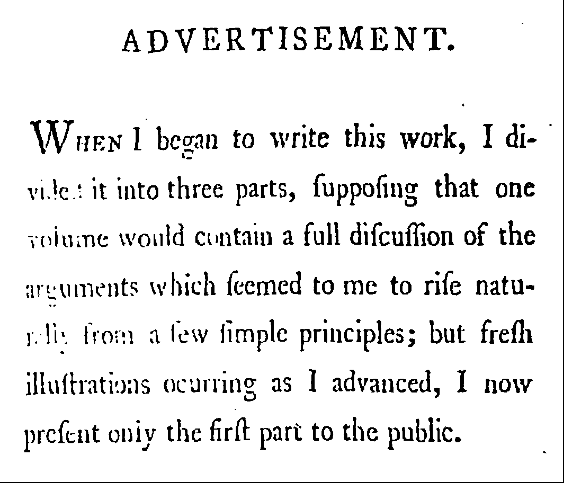

Wollstonecraft signals that a series of “fresh illustrations” structure the text

Rights of Woman presents an anti-canon of texts which had conspired over generations and across different societies to construct the feminine “character,” making the book a forensic treasure trove of gender normative evidence, annotated by an expert editor (and she had perhaps edited two anthologies by this time). In short, if we see A Vindication of the Rights of Woman as a continuation of her practice as a literary, political, and cultural commentator, then a new book comes into view, a book in which each text under consideration links to others, across genres and literary generations, as Wollstonecraft excavates a self-generating ideology of gender, or as she puts it so well: “The Prevailing Opinion of a Sexual Character Discussed.” The title of Chapter 2 is so perfect that she saw no need to give Chapter 3 a new title, calling it, “The Same Subject Continued.” In fact, these two chapters contain, by my quick count, at least 53 allusions, references, and quotations of influential texts, but not “influential” in the elitist sense. The primary criterion for inclusion is not how “great” a work is but how much of an effect it has had upon notions of femininity. In the midst of dismantling the work of an allegedly lascivious and condescending writer of conduct manuals, Wollstonecraft drops this hammer:

As these volumes are so frequently put into the hands of young people, I have taken more notice of them than, strictly speaking, they deserve; but as they have contributed to vitiate the taste, and enervate the understanding of many of my fellow-creatures, I could not pass them silently over.

We can look at Chapters 2 through 5 as a unit, one in which Wollstonecraft methodically works through a huge range of genres, generations, and authors. Chapter 5 itself is essentially a mini-anthology of five reviews, each covering a representative book or genre, and is the last chapter in the book to feature a rich interplay of texts. Chapter 6 is the proper and organic endpoint to the literary critical portion of the book, as it supplies a philosophical and physiological argument for the effect of texts upon impressionable minds. Again the title of the chapter says it so well: “The Effect which an Early Association of Ideas Has upon the Character,” apparently drawing on Joseph Hartley’s proto-psychological theories of how the mind is held in thrall by random ideas that group together and roam the mind in “posses” (which in turn come from a midcentury debate over John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding). In Chapter 6 in particular and in Rights of Woman in general, this analysis expands into a proto-feminist theory: “Everything that they see or hear serves to fix impressions, call forth emotions, and associate ideas, that give a sexual character to the mind,” and to pin part of the blame on books, she specifies that, “the books professedly written for their instruction, which make the first impression on their minds, all inculcate the same opinions.”

Wollstonecraft expands the view of the vulnerable recipients of gendered education to include male figures such as the great writers themselves, Milton, Rousseau, and “most of the male writers who have followed his steps.” Notions of gender identity don’t just turn young women’s heads, but also act upon authors, even quite established and otherwise judicious ones. That is why she saves her most biting epithets in Rights of Woman for writers, not readers, which constitutes a break from most of the reviews up to 1791. In conclusion, Rights of Woman is a brilliantly orchestrated set of literary commentaries. Who but a practicing educator, critic, and journalist could construct such a comprehensive anthology of texts which build an image of women’s “character” and back it up with pointed analysis of the authors she engages with? Who but a hardworking woman who spent her days earning a living by writing about books?

[1] To get an overview of the state of the art, it is worth a look at the Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, volume 4, but for women’s literary criticism of the long eighteenth century there is the gem, Women Critics, 1660-1820 (1995).

[2] One of the best treatments of the literary nature of Wollstonecraft’s first Vindication is still the brilliant and useful book by Virginia Sapiro, A Vindication of Political Virtue: The Political Theory of Mary Wollstonecraft (1992).

[3] A very notable exception was Emma Clough’s A Study of Mary Wollstonecraft and the Rights of Woman from 1898 (the work of one of the first female doctoral students in the United States).

[4] I am very much indebted to Virginia Sapiro, Mitzi Myers, Caroline Franklin, Mary Waters, Susan Wolfson,Daniel O’Neill, many others who have brought Wollstonecraft’s work as a professional reviewer further into the light.

Fiore Sireci (PhD Edinburgh) is on the faculty of Hunter College (CUNY) and The New School for Public Engagement, where he teaches interdisciplinary courses in literature, philosophy, and social history. Professor Sireci is a former Fulbright scholar in literature pedagogy. He has recently presented at the American Academy in Rome, publishes regularly on Mary Wollstonecraft, and is completing his second book, After Italy, a memoir and local history.

June 29, 2018 at 10:18 am

It’s highly enlightening and very interesting to learn that Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Woman includes so much commentary on literary figures, including Milton and Rousseau. The author does an excellent job of showing how Wollstonecraft’s early training as a writer–reviewing and literary criticism–was put to excellent use by her in her great pioneering work of feminism.

July 12, 2018 at 3:48 am

An extremely well argued, critical and scholarly article.