By Anne Schult

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, in many ways the most well-known proponents of conceptual nomadism, took the nascent idea of the ahistorical nomadic and its complex relationship to the state one step further. Their ideas on nomads were first tentatively formulated in L’Anti-Oedipe (1972), which introduced the technology-infused universe of machines, codes, and flows that fueled their shared narrative of state critique. Here, the nomadic appeared linked up with the schizophrenic as a resistance in form to capitalist modernity, suggesting the same connection between nomadism and anti-psychiatry that Duvignaud alluded to around the same time. Yet, in their follow-up volume Mille Plateaux (1980), the nomadic began to take shape as a concept more fully and was presented as a comprehensive anti-statist, anti-structuralist “Traité de Nomadologie” that has subsequently taken on a life of its own.

To start with, Deleuze and Guattari made a clear distinction between nomadism as a concept rooted in historical nomads and their suggested nomadology as a distinct study of the nomadic as characteristic. The latter, they posited, was recognizable as a state of “becoming, heterogeneity, infinitesimal, passage to the limit, continuous variation” (363), which in social organization presented itself as a rhizome structure instead of being centralized around a power core. Previous writers, they wrote, might have recognized the nomad, as told in and by state history, but not the defining features of the nomadic. Collapsing the pre-modern and the post-modern into a timeless vortex, nomadic societies in their account could not become extinct or be superseded by the state because the two forms no longer stood in a sequential relationship to one another. “It is true that the nomads have no history,” Deleuze and Guattari thus asserted, “they only have a geography” (393).

Paradoxically, what emerged from this purely spatial relationship between state and nomad was a very particular vision of the future that was thus not so much about life after the capitalist state, but life with and beyond it. Notably, it no longer required the figurative nomad, as Deleuze and Guattari insisted specifically that it had no embodiment, such as in the form of postcolonial subjects or migrant, in the present. Rather, nomadology was to be understood as a rigorously practical anti-structuralism that could arise both from without and within the state. After all, they pointed out, nomadic features were detectable in nearly every aspect of contemporary society: music, architecture, games, technology, mathematics, science. The idea of “nomad thought” in Mille Plateaux thus formed a sub-commentary on the authors’ own endeavor of text-as-practice.

The premise of this “nomad thought” was that in order to truly resist the state, one did not only have to do so in social organization, but actually think against and outside of state forms. The first difficulty, according to Deleuze and Guattari, was to recognize the nomadic beyond its opposition to the state, as the contemporary way of thinking has been conditioned by the state apparatus, creating an interiority of binaries. Seeking examples, Deleuze and Guattari dove into the history of Western thought and declared Hegel and Goethe to be “state thinkers” (356)— following the intrinsic rules on a limited intellectual territory controlled by the state—while applauding their nomadic counterparts Kierkegaard and Nietzsche. The latter, they wrote, categorically rejected universality and instead deployed their thought “in a horizonless milieu that is a smooth space, steppe, desert, or sea” (382) as a particular milieu, thus acting as vectors of deterritorialization and posing questions and problems that were always local and particular.

Although it had its echo within and beyond French theory, Deleuze’s and Guattari’s “Traité de Nomadologie” marked both the peak and the beginning of decline of a more critical concept of nomadism. Much of contemporary scholarship has put forth the argument that theories around nomads—in particular those proposed by Deleuze and Guattari—mark just another form of neo-primitivism and remain ignorant of actual nomadic populations, such as the Romani, in the French or broader European context. Indeed, towards the end of the Cold War, the concept became increasingly streamlined, globalized, commodified, and institutionalized. As a result, the nomad encountered in Western popular culture today is typically taken to be a rootless post-industrial subject eluding the bureaucracy of the state apparatus by way of digital technology but existing entirely within the logic of capitalism and consumer culture. Perhaps the changing political climate proved problematic: In its insistence to be divorced from migrant bodies, nomadism appeared to have little to offer for understanding the growing “immigrant problem” that emerged in the French electoral politics of the 1980s. Similarly, the idea of a “deterritorialized” world was uncomfortably mirrored in the process of globalization, which became a prime concern in both politics and theory during the 1990s. But for a brief moment, in the post-1968 era, nomadology offered a glimpse of one possible landscape of future France.

***

This piece marks the third and last installment in a three-part series on nomads and the nomadic in 1970s French thought. The first part explored anthropologist Pierre Clastres’s projection of nomads as an alternative, more egalitarian society within prehistory that has been lost due the rise of the capitalist state. The second part focused on the short-lived interdisciplinary journal and collective Cause Commune and its attempts to resituate the nomadic as a subversive tactic for the present. This final post will take a step further by exploring the development of nomadism into a broader, more abstract antistatist concept in 1980s French philosophy.

Anne Schult is a PhD student in the History Department at New York University. Her current research focuses on the intersection of migration, law, and demography in 20th-century Europe.

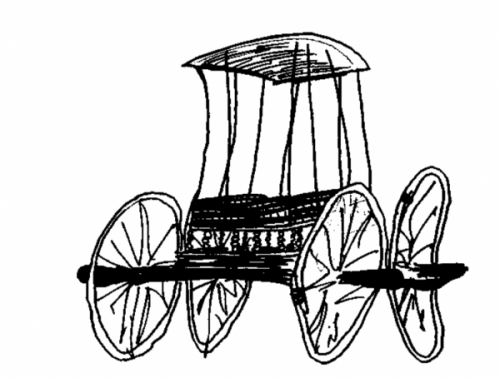

Featured Image: Nomad Chariot, Entirely of Wood, Altai, Fifth to Fourth Centuries B.C. Illustration taken from Mille Plateaux (1980).

Leave a Reply